How Isthmus’ North Kumutoto design enhances Wellington’s waterfront

Kumutoto’s original premise back in 2004 was to connect Wellington’s city with the sea that surrounds it. It was a time of intense inner-city development where urban culture had liberalised as newly assorted street cafés, nightclubs and retailers continued to grow in the capital city, and so the development ensured there was still ties to the past – and to the natural elements surrounding the city. The 2004 masterplan was developed by Studio Pacific Architects in association with Ralph Johns.

North Kumutoto is situated to the north of Queens Wharf, an integral link between the city and the working harbour. It features a series of public spaces for leisure activities that look to add more vitality to the waterfront.

“You can’t beat Wellington on a good day…” Johns tells me – words that have perennially echoed from the rooftops of our capital city. And in lots of cases, the saying rings true. The city’s strong history of public art coupled with a sort of urban eclecticism is only pronounced by its distinct weather patterns, but this weather wasn’t a deterrent in the ambitious design thinking behind Kumutoto.

“….but when it is windy, it is windy. When it is wet, it is wet. So when we designed public space it’s about embracing the elements not trying to control them.” Johns says.

A key part of the project is the new public space, occupying ‘Site 8’ of Wellington’s waterfront frame work, which extends from its original body of work on Kumutoto Plaza. Originally intended to be a building, the site represents a shift from the initial master plan. Instead, it’s focused on an anvil-shaped timber pavilion that overhangs the coastal edge.

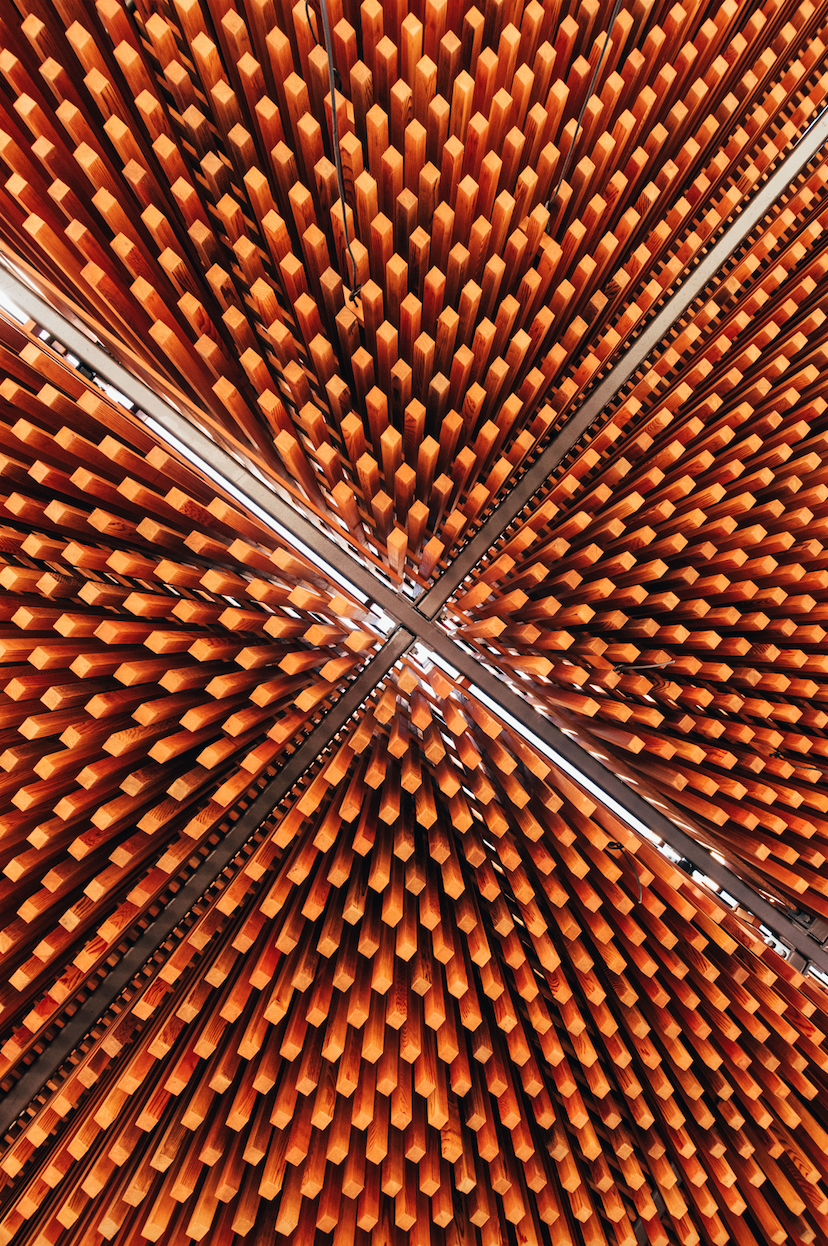

John says that that the pavillion is purposefully not waterproof, but instead designed to expose the elements. He muses, “It’s like a big puhutukawa tree; it isn’t waterproof, but it does provide shelter and shade,” a quality that is culminated by its form. It is composed of a matrix of timber battens formed into cassettes and attached to steel-lattice trusses, which hover lightly overhead before cascading down the pavilion edge. Thus, it offers a place for onlookers to celebrate the harbour without being obtrusive.

“This is an integrated work of landscape and architecture. Isthmus’ designers worked in the overlap between these disciplines to create a building that is part of the landscape; or a landscape that is part of the building. It signals the move we have made to become a more integrated design practice focussed on land, people and culture,” Johns says.

“It is one of the first built projects that shows the potential of uniting architecture and landscape under a common design philosophy.”

When it is windy, it is windy. When it is wet, it is wet. When we design public space, it’s about embracing the elements.

The recognition for heritage is sewn throughout the Kumutoto precinct. To provide some background, the place holds spiritual significance to the Te Atiawa iwi and takes its name from the historic Pa which once overlooked the area. The name, Kumutoto, holds further significance.

“At the start of the project the site was called North Queens Wharf – a colonial name,” Johns says. “The name of Kumutoto emerged from the stream that flows out into the sea that has been stuck in a pipe for years. We reclaimed the history and ecology of the site at the coastal edge.”

A key part of the project saw the declamation of the buried mouth of the Kumutoto Stream, which now allows the sea to be let in and invites the public to empathise with its natural inhabitants. Additionally, the public space considers the natural flora and fauna, notably, the koror? – or little blue penguins.

“We tried to create a more varied habitat for the plants and for the animals. It creates habitats for the little koror? and a lot of the planting is native species that exist around the Wellington harbour. Historically, it was a place for flax trading, the flax references the trade as well as the ecology,” Johns says.

Kumutoto has picked up a number of awards, too. This includes a Gold at the Best Awards where it was noted for its ‘beautiful level of craftsmanship and detail with an underlying Pacific feel.’ Further descriptions have attributed Kumutoto as a ‘flexible’ and a ‘wonderfully communal’ precinct.

Johns adds, “It is a working waterfront. The materials are simple, exposed, industrial and really robust. It is not fussy and urban – it is chunky and purposeful. There is something about designing like that which makes a place feel authentic. It is an urban waterfront, and it is not trying to be something it isn’t. It keeps things honest.”

He says the waterfront has acquired a particular design language over the past 20 years, in part thanks to the Wellington Waterfront’s technical advisory group, which holds a design review process for every project. This has ensured that materials, details and design principles are related across the wider waterfront environment. Consequently, the evolution of the waterfront maintains a balance between consistency and diversity. Asked if Kumutoto references international waterfront developments, Johns simply says “no”.

“Kumutoto is Kumutoto because it is Kumutoto. It has referenced the place. The other points of reference are other projects around the Wellington harbour, the work at Oriental Bay, as well as the design of Waitangi Park, and Taranaki Wharf.” Some of these neighbouring spaces have been designed by Isthmus, most others by Wriaght Assocites. This parallel design approach has managed to forge a certain vernacular upon the Wellington harbour. Johns characterises this as simple, exposed, industrial and robust.

After 14 years, the master plan for Kumutoto is still not yet fully built-out. The last piece of the puzzle will be Site 9, a building in development by Athfield Architects.