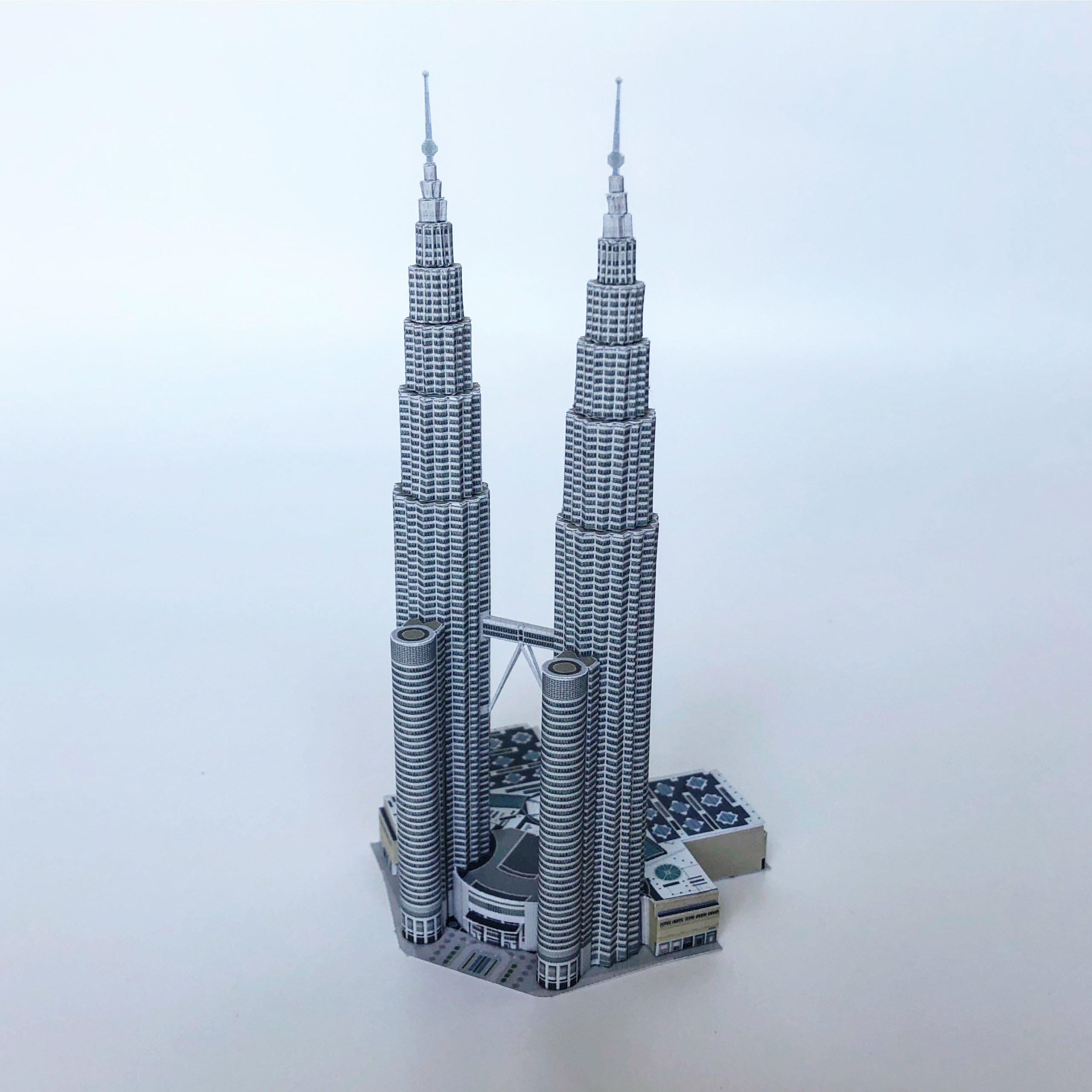

Photo credit: Sophie Heyworth

Tim Hogarth’s paper models of skyscrapers may be small but they’re perfectly formed, the result of an intense hobby for the architectural graduate for more than a decade. Tim, who works at Auckland based architectural practice Box, has been fascinated by the modelling of the tall buildings that define the world’s skylines since he was a teenager. While his classmates were skateboarding at the park or going goggle-eyed gaming for days, he was channelling his interest in high-rise towers. “I was your classic introvert,” he says, “being at the computer researching images was my escape.”

To be fair, urban settings had long held a fascination for Tim. As a child on family trips and in his spare time, he’d pass the hours with a pencil and paper on, drawing maps of imaginary places from a bird’s-eye perspective.

By the time Tim was 17, he’d moved from 2D to 3D in the application of his passion. In his last year of high school and, in between studying towards NCEA, he was chatting in skyscraper forums to fellow enthusiasts around the globe. The very first building he made was the Bank of China tower in Hong Kong. Today, he describes that paper model as “humble in comparison”. Being at architecture school instilled a sense of ambition and drive to make the models the best possible. “I wanted to explore how detailed I could make the models, so that the buildings would be a strong conversion of the real thing.”

In holidays between semesters, Tim would eschew visits to the beach in favour of virtual expeditions and refining his methodology. Mostly the process starts with an exploration of skyscraperpage.com where diagrams of about 34,000 structures are displayed. Once a building captures his imagination, it’s time for research…then more research…and yet more research. First he’ll look at photos online then search Google maps street view, which has advanced his cause significantly over 10 years. “Satellite images are so much better now,” he explains, “the finished model is only as good as the information you can find.”

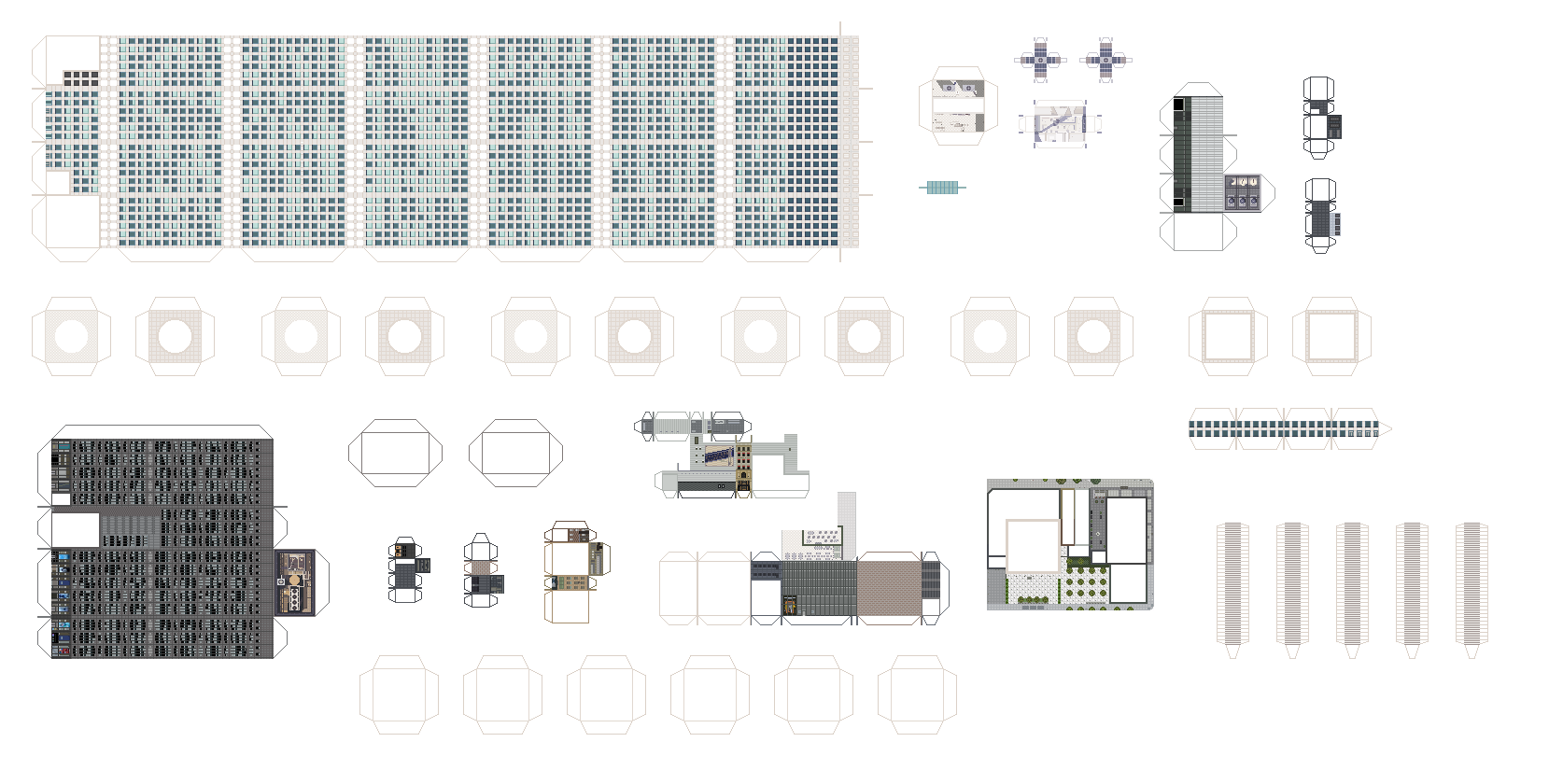

He’ll spend hours zooming in on the façade and the features. “The cladding has so much texture; it’s never just a solid colour. There are always undulations…colour variation in the mid-floor. Surface grilles, slots in the glazing for washing rigs, even the blinds and curtaining.”

Tim uses Microsoft Paint to draw the skyscrapers, employing its scale ruler to ensure all his models are the same scale. “One pixel equals 0.5 metres,” he says. Then he’ll fill in the detail with pinpoint accuracy on all four elevations. It takes weeks of meticulous design work before he’s happy to press print.

That’s when the task moves from digital to dextrous. Tim puts his models together using regular printing paper. “The more complex forms can be really challenging. You learn when to use a craft knife or scissors, when to press folds or when to pack out the middle so the models stay rigid. I’m aiming for 100 per cent accuracy, so if they don’t assemble exactly right I will tear them apart and start again.”

Tim’s demanding hobby has allowed him to inhabit his own microscopic universe, to travel vicariously, and to appreciate the value that a well-executed skyscraper can bring to a sense of place. One of his favourite buildings is the Willis Tower (formerly the Sears Tower) in Chicago. “Most people think New York was the first city to have high-rise buildings, however it was Chicago – they grew up after the Great Chicago Fire in 1871 burnt down many of the timber buildings.”

Others on his top-ten list include: the Paris Courthouse complex by Renzo Piano – a series of stacked volumes; the 76-storey Frank Gehry tower at 8 Spruce Street in New York (“I love the rippling, shiny cladding”) and the Transamerica Pyramid in San Francisco, with its elegant tapering form that is a sculptural punctuation on the skyline.

As far as buildings in our most populous city go, Tim has modelled the Sky Tower and the Auckland Council Civic Administration Building, both completed for his architectural master’s thesis. They help to contextualise New Zealand’s involvement in the international scene. Having two buildings modelled among his 44 models is a statement in itself; our high-rises are humble in comparison to the blockbuster-budget, big-scale projects of other cities. “Some people view skyscrapers as just crude expressions of commercial wealth, but they often become part of our civic identity. The Sky Tower is now a node in the city that helps us navigate, and an icon that contributes to the urban tapestry.”

In a glass display case in the reception area at Box, Tim’s family of buildings from disparate parts of the globe are brought together. Finding the time to add to his collection is tough, however he’s made a start on the Bank of China tower that launched this demanding hobby. It’s a re-make of architect IM Pei’s prism-like vision that grows into the heavens like a bamboo shoot. He knows his skills have advanced so it will be a better version. But it’s just one in a queue of skyscrapers he’d like to produce. When it comes to paper modelling of the world’s tallest structures, the sky’s the limit.

For future updates on Tim’s paper models follow him on Instagram, at timhpictures.