The Guardian has estimated that the additional NOx emissions of the cars known to include the software may equate to 250,000 to 1 million extra tonnes every year, or the equivalent of all of the UK’s NOx emissions from power stations, vehicles, industry and agriculture combined. Vox has calculated the VW’s additional emissions “can be expected to lead to an additional 5 to 27 premature deaths per year”.

Obviously this is all very bad news for VW (worse than Enron according the FT), which has earmarked US$7 billion to pay for fines connected to its fraud, though could face fines up to US$18 billion (not to mention the costs of recalls, lost sales, or any other penalties).

But is it bigger than that? Are all car companies stretching the rules? Is what we expect from cars – high performance, high efficiency, low cost, low emissions – just impossible to deliver?

VW aren’t the first to be caught out. Car companies have been using defeat devices to pass emissions testing almost since testing began. And, perhaps more importantly, it now looks like most car companies are somewhat-less-than-honest in the testing of their vehicles.

Last week, the International Council on Clean Transport (ICCT), the clean air advocacy group who caught out VW, issued ‘From Laboratory to Road’, a white paper report detailing how the average gap between real-world, road-tested emissions and official testing has been growing steadily since 2001, taking a suspicious upturn with the introduction of mandatory emissions reduction targets in 2009.

According to the report, which averages several independent on-road test and compares the results with the official EU testing results, average carbon dioxide emissions of diesel cars are 40% higher than official testing. In 2001 it was less than 10%.

And VW doesn’t even have the largest gap. In German testing, cars made by Daimler (which includes Mercedes-Benz) had a gap of nearly 50% between road-tested emissions and official emissions, while VW’s gap was, on average, about 37%.

While use of a defeat device is clearly fraudulent and illegal, car companies are using techniques which the report says “strictly follow the letter of the legislation” such as: disconnecting brakes and alternators; stripping out unessential features; using specialist lubricators; recharging the battery; duct taping indents, grills and gaps; and simply deducting 4% from each result.

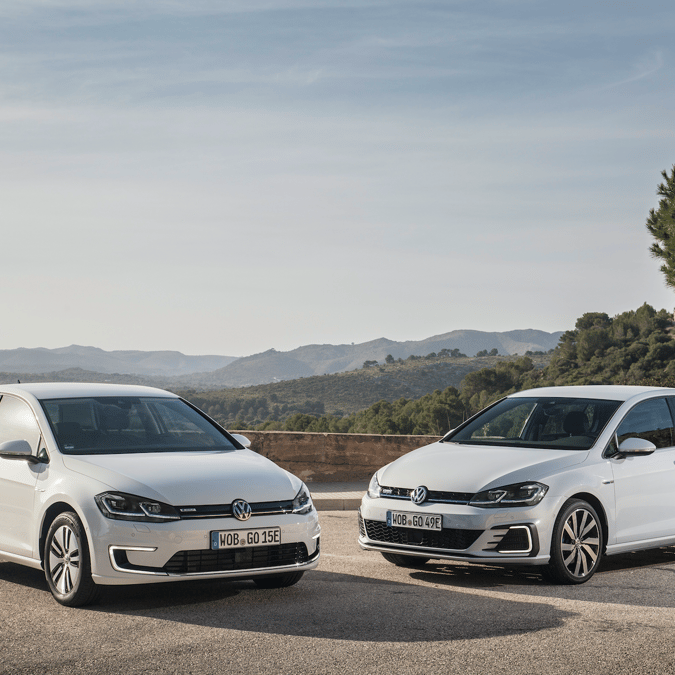

Image: Advertising for Volkswagen’s TDI “Clean Diesel” engine, which won multiple Engine of the Year awards and is implicated in the scandal

What’s going on here?

In the EU, car companies pay certified testers to perform the testing, in the car companies’ own lab, so the testers are dependent on the car companies to renew their contracts year-on-year.

In the US, things are a little tighter, especially concerning diesel vehicles, but VW weren’t caught out by scrutinous official tester or overzealous government employer, but by the independent testing of an until-now little-known advocacy group.

So what are we supposed to do with all this information? Do we have expectations that car-makers just can’t live up to?

We know cars are bad for us and bad for our planet. But no matter how much we know this, we struggle to kick the habit. Cars are just so convenient. There’s no waiting at the bus stop; no overpopulated, over-humid traincar; no high school students screaming at each other. They take us from door to door in the privacy of our own little metal box.

And no matter what car we drive, we’ve been collectively comforted by what looks to be vast improvements on the last few years. Clean diesel! Biotech fuels! Efficiency!

But what the VW scandal has done (other than lost VW a whole heap of money and shattered its reputation) is shown us, inexplicably, that combustion engine cars are huge pollutants, and although we expect them to get cleaner and greener, we also expect them to be affordable, and to have the performance and handling of the cars that were made before people cared so much about how much carbon and smog they were pumping out.

The ICCT’s study shows us that not only is the emissions testing flawed, it’s almost impossible for car companies to truly live up to. And maybe that’s a good thing. Maybe this whole affair will strip away our self-delusion.

If we really want to move away from combustion engine cars, now’s the time. But if we want to continue to drive pollution machines (Full disclosure: I drive a pre-defeat-device VW station wagon so I’m scolding myself here too), let’s be honest about what we’re doing. Diesel isn’t clean. And, despite the colour of the pump, petrol definitely isn’t green.

So maybe we’ll soon look back on this as a good thing, as a tipping point for real movement away from combustion engine cars.

As Richard Branson told CNBC last week: “What’s happened to Volkswagen is actually positive news in that hopefully the car manufacturers will do the right thing and will invest in the future.”