This is the story of two researchers who devised a wireless monitoring system for lab animals.

Every time the innocuous beep of a smartphone notifies us of the arrival of a cat video, Facebook message or gif, we take for granted that a chunk of data has travelled through the air to reach us. And while such instances of wireless magic have become ubiquitous in the world of tech gadgetry, they didn’t play much of a role in medical research until a pair of Kiwis decided to innovate in this field.

Every time the innocuous beep of a smartphone notifies us of the arrival of a cat video, Facebook message or gif, we take for granted that a chunk of data has travelled through the air to reach us. And while such instances of wireless magic have become ubiquitous in the world of tech gadgetry, they didn’t play much of a role in medical research until a pair of Kiwis decided to innovate in this field.

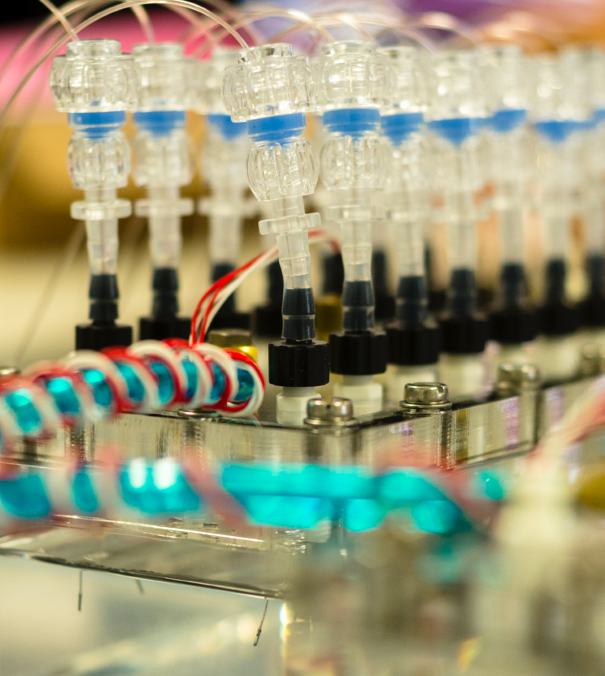

About 10 years ago, Professor Simon Malpas and Dr David Budgett devised an implantable telemeter, which once surgically inserted into a test subject, allows for the wireless monitoring of physiological signals in a small animal.

Prior to the development of this device, medical research used various invasive methods that interfered with the mobility and comfort of the subject, which rendered results that weren’t necessarily reflective of the naturally comfortable human condition.

So rather than monitoring the effects of a drug on a sedated subject attached to a series of cables, physiological data can now be collected wirelessly while the animal moves around freely.

You’d be forgiven for expecting to find a pair of wild-haired scientists surrounded by whiteboards filled with esoteric notations in the Millar offices. But the reality is quite different.

You’d be forgiven for expecting to find a pair of wild-haired scientists surrounded by whiteboards filled with esoteric notations in the Millar offices. But the reality is quite different.

Clad in short-sleeved shirts and sporting neat haircuts, Budgett and Malpas have the appearance of a regular pair of Kiwi blokes on a summer day.

And when they start chatting, it becomes apparent that they have another Kiwi trait: a seemingly inexhaustible resource of humility.

When asked about how they came up with such a revolutionary idea, Malpas starts by sharing a few jokes about memory loss before Budgett steps in to give an almost mechanistic account of how the idea came to fruition.

“Simon had a scientific problem he was trying to solve, and it required a bit of technology. So he came and spoke to me because I’m an engineer, and he said, ‘here’s an issue can we get some data from these animals?’ and I said, ‘sure’. Now about 10 years later we’ve just about cracked that problem.”

This nonchalance also extends to Malpas, whose explanation for starting the business makes it sound as though he couldn’t find what he was looking for on the aisle of a DIY store.

“A lot of businesses grow out of trying to solve a problem they can’t buy the solution for, so they go out and make it,” he says. “And as a result of solving that problem or attempting to solve it, they realise that there’s a market and that other people have a similar problem.”

In 2004, when Malpas and Budgett first incorporated their company, they launched it under the name Telemetry Research. It didn’t take long for their unique offering to get noticed, and with this attention came interested buyers.

For about eight years they resisted the urge to enter into any agreements with other companies, but at the end of 2011 when Houston-based Millar knocked on Telemetry’s doors and proposed a merger, they went for it.

For about eight years they resisted the urge to enter into any agreements with other companies, but at the end of 2011 when Houston-based Millar knocked on Telemetry’s doors and proposed a merger, they went for it.

Although Telemetry Research had to adopt Millar’s name as part of the agreement, Malpas says the company still identifies as Kiwi.

“The company we’ve merged with isn’t big,” he says. “It’s not like BP, Microsoft or Google, where you would be swallowed and made to fit. It’s a relatively small, family-owned company.”

He concedes that the transition has had a few hiccups along the way, though.

“Whenever you merge two organisations, even if they were neighbours, you’re going to have different systems and processes,” says Malpas. “And I think it comes down to whether you have a common philosophy or a common aim. And we do.”

Adds Budgett: “We have very complementary capabilities. We’ve got fantastic technology and tremendous momentum in innovation, but to get this into a clinical product requires a disciplined approach in order to meet the regulatory environment. And the American side has got all those expertise and they know how to progress along that pathway.”

?

?

To Malpas and Budgett, this pathway doesn’t end at clinical testing on rats. Their aim has always been to develop the technology to an extent where it could potentially be used in humans for the purposes of monitoring.

“The core capabilities of having a radio system to transmit data, and having wireless power to transmit through the skin means you can have an implantable device, which has the potential to last a lifetime, to service the patient’s needs,” says Budgett.

And while the thought of microchips being inserted into the body would probably trigger an Orwellian reflex in conspiracy theorists, the life-saving potential of being able to passively monitor the physiological conditions of a person, who for instance has a pre-existing medical condition, is definitely something worth striving for.