Sometimes the things you do for work are just that – work. Other times they have a profound impact on you. This happened to me recently as I was researching a presentation on how a STEAM approach to our economy will deliver more than a STEM approach.

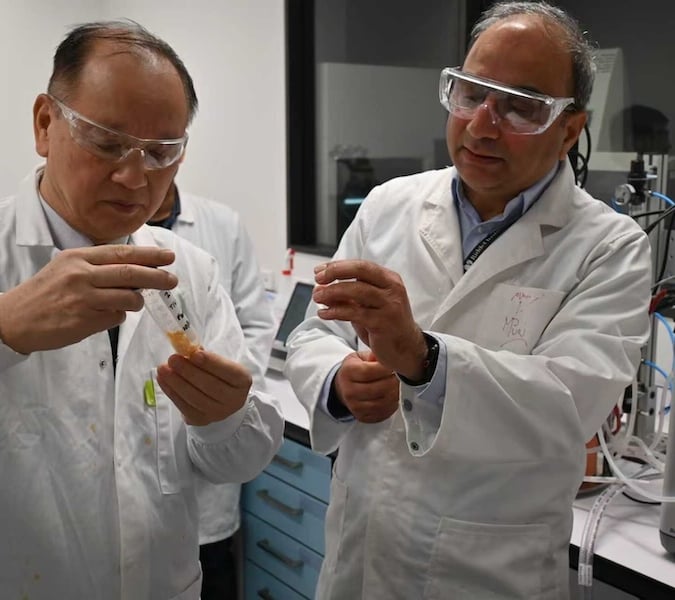

Back in Auckland to launch new NMR Spectrometer @AUTuni and then open new ICT graduate school @AucklandUni. #science #stem

— Steven Joyce (@stevenljoyce) February 24, 2016

The term STEM refers to science, technology, engineering and math. If you follow the Minister of Everything, Steven Joyce, on Twitter, you’ll frequently see #STEM in his tweets about the New Zealand economy. He’s so committed to it as seemingly the only way to diversify us from a dairy-based economy that the Tertiary Education Commission (he was the Minister of that too) has shifted funding towards STEM subjects. But, in doing this, I think New Zealand is missing an opportunity to leverage and grow an area of the economy that already contributes significantly to our GDP: our arts and creative sector.

We have incredibly creative people and amazing creative businesses in New Zealand. Our games, books, music and movies are known throughout the world. Our architects, fashion designers and advertising agencies generate revenue offshore as well as at home. We proudly call ourselves a ‘creative nation’ and have the evidence to back it up. Some of that evidence comes in the form of the Global Creativity Index (GCI). Published by the Martin Prosperity Institute in Canada, the GCI measures the three T’s of economic development – Talent, Technology and Tolerance. New Zealand makes the top ten in all three categories and is third in the world overall.

We’re also well on the front foot when it comes to having the digital infrastructure that is needed for a creative economy. A 2015 report classified New Zealand as having “stand-out” digital infrastructure along with Singapore, Hong Kong and the US. This means we have highly evolved digital eco-systems, competitive e-commerce markets, cutting-edge infrastructure and sophisticated domestic consumers. To maintain this level of achievement we need to continue to fast-track innovation and sell to the world, not just to ourselves. Exporting is a must! The data on creative occupations in New Zealand already shows us that as many creative people work outside of the creative industries as work in them. It also shows that creative occupations are considerably more productive than many others in the New Zealand workforce. Our creative skills and thinking are already helping sectors such as technology to develop great products.

One industry in particular that is a perfect storm of creativity and tech is our games industry. The overall value of this industry in New Zealand has grown 450 percent in the past four years. Growth in the past 12 months was 13 percent and export earnings account for 92 percent of the revenue. The industry employs artists and musicians in equal numbers to software developers, and develops games not just for entertainment but also for education and wider learning.

Steve Jobs regularly pointed out that the biggest difference between Apple and all the other computer companies is that Apple always tried to marry art and science, with the original Mac team having backgrounds in anthropology, art, history, and poetry. Apple devices wouldn’t be the same without the creativity that took a product that was purely functional and made it desirable. It’s the creative aspect that makes people want the product. What would Facebook look like if it had only been developed by programmers instead of a team of content strategists and designers? Xero, a New Zealand tech success story whose tagline is “beautiful accounting software”, wouldn’t be as beautiful if it wasn’t for the creative environment and thinking of its product development team. The relationship of arts to innovation has a long history, with obvious examples such as Leonardo da Vinci, whose many scientific discoveries benefitted greatly from his artistic interests, and vice versa.

Stanford University recognised this three years ago. This light-bulb moment can be partially attributed to the success of some of the university’s alumni who include the founders of Google, Netflix, Instagram and PayPal. Now, all students at Stanford, regardless of their course major, must take a class in creative expression. There are 161 classes to choose from, from Laptop Orchestra or Shakespeare in Performance – all designed to help students out of their subject-specific comfort-zone and to introduce them to a place where new ideas and ways of looking at the world are stimulated. This approach has been explored by the OECD’s Centre for Educational Research and Innovation which found that vocational training isn’t enough anymore and that arts graduates are more likely than others to be involved in product innovation.

The export opportunity from New Zealand creativity is significant. With the click of a mouse we can now send digital products to international audiences anywhere. And we can also use the internet as a business tool that lets our architects, our fashion designers and our advertising agencies communicate with clients and share business information in places other than at the bottom of the world. Use of the internet is a game-changer that grows the market for New Zealand content from only 4.5 million customers to a worldwide audience and we need to maximise our use of it to deliver more value back to New Zealand.

Our arts and our creative industries are all too often only viewed through a cultural lens rather than an economic one. In doing this we’re missing an opportunity to grow not only creative businesses and creative exports but also the added value that creative people will bring to products and services in the science, tech and engineering fields. It’s the A for arts that can help deliver the A for added-value. If we support and develop Kiwis who use the right side of their brain (the creative side) more than they use the left (the logical side), we’ll have a great platform for innovation and a 21st century knowledge economy.

But first, we have to convince certain people – here’s looking at you Minister Joyce – to say STEAM, not STEM.