As a general rule, it’s best to approach any subject of hype with a healthy degree of skepticism. And when it comes to 3D printing, there’s no shortage of hype. Tech pundits predict outcomes as wild and futuristic as revolutionizing healthcare, ending hunger and homelessness, and killing manufacturing as we know it. But is a printer really going to change the world that much?

Yep, probably.

Already there’s serious R&D being put into all the above eventualities. The University of Southern California designed a concept printer capable of printing a concrete house, with implications for disaster relief and affordable housing, and the world’s first 3D printed house is already under way in Amsterdam. NASA is developing organic wood secretion for printing trees in space, while Modern Meadow, a company partially funded by Google’s Sergey Brin, is researching synthetic meat printing. Meanwhile a number of amateurs and academics are already printing 3D prosthetics. Printable human organs aren’t so far off.

Already there’s serious R&D being put into all the above eventualities. The University of Southern California designed a concept printer capable of printing a concrete house, with implications for disaster relief and affordable housing, and the world’s first 3D printed house is already under way in Amsterdam. NASA is developing organic wood secretion for printing trees in space, while Modern Meadow, a company partially funded by Google’s Sergey Brin, is researching synthetic meat printing. Meanwhile a number of amateurs and academics are already printing 3D prosthetics. Printable human organs aren’t so far off.

Today’s tech largely prints plastic better suited to prototyping than a finished product, though that will change. January’s International Consumer Electronics Show (CES) in America showcased printers capable of printing ceramic and chocolate — but nothing as advanced as wood, concrete or flesh. But that doesn’t mean it isn’t quietly changing the way business is done. Fisher & Paykel Healthcare bought its first 3D printer three years ago, and since then has brought all its prototyping in-house rather than contracting out to machine shops.

Product development manager Peter Graham says this enabled the company to work much faster and smarter, cycling through design iterations of

its home healthcare devices quickly and incorporating the marketing department’s opinion early on in the process. Traditionally a prototype design might have been limited by the manufacturing technique and taken three weeks or more to get back; Graham says printing can now be done overnight and with unlimited complexity.

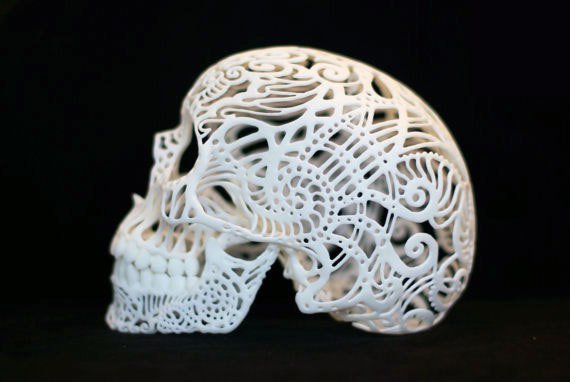

Handling complexity opens up a new world of customisation opportunities for businesses. Platforms like Shapeways allow users to connect with designers and order customised versions of their products. Mostly it’s simple things like iPhone cases, but it won’t be long before 3D scans of body parts allow users to endlessly tailor products to a customer’s body. Already, New Balance has tested customised plates on running shoes, and startups have created everything from customised orthotic insoles to Star Trek figurines. Mass production might eventually make way for mass customisation, because the business costs of doing so will no longer be prohibitive.

Until recently, the wieldy tech and high cost of 3D printing kept it confined to manufacturers and businesses who could justify spending time and money on acquisition and maintenance. Only the most technically inclined consumers used the printers; even affordable versions, such as the open-source selfreplicating RepRap, are hardly kitset assembly.

That’s all changed in the last five years. Paul Francois, product manager at Auckland-based printing distributor Comworth, says improved technology and decreasing prices have lowered the barrier to entry and produced user-friendly models. In fact, Comworth is busy introducing New Zealand’s first sub-$1000 3D printer. Schools and libraries are among the first adopters, but if the desktop models at CES were anything to go by, a future where every home has a 3D printer alongside the old Epson is suddenly very real.

The implications of desktop 3D printing adoption are huge. It puts the power of small-scale manufacturing in the hands of everyone with access to a printer. If your dishwasher needs a new part, print one. Sure, the design will be needed to do that – and manufacturers might consider producing licensed designs of their parts either at extra cost or as added value, but that will only work as long as more people are prepared to obtain those designs legally instead of file sharing.

Francois says 3D scanners, which are still pretty expensive, will eventually come down in price and can be used to scan existing parts to reverse engineer a design. No licensed design required, and no way of enforcing intellectual property protections. Great for consumers, but possibly not so great for businesses who don’t get out in front of the threat it presents.

“With the development of 3D printing technology beyond prototyping and into actually producing finished products, which is not here yet but coming,

that’s going to fundamentally change the way consumer products retailers have to think about their businesses,” says Anton Gibson, senior partner at intellectual property law firm AJ Park.

“You’re going to see retailers, manufacturers, importers and all aspects of the delivery chain grapple with that in the relatively near future.”