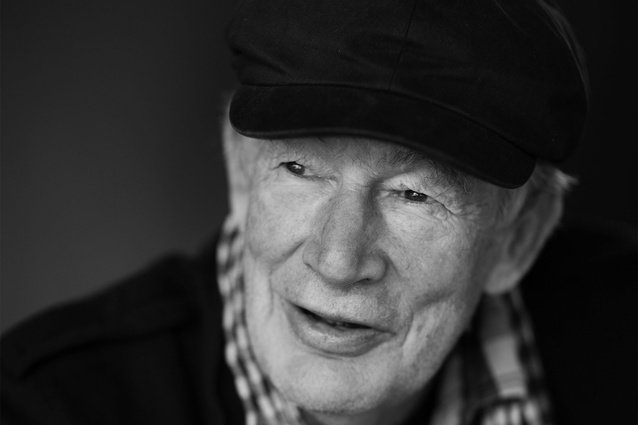

Sir Ian Athfield was a stalwart in New Zealand architecture, with a wonderful curiosity in design and an ability to think big. He was known as a designer with a rebellious streak – an innovator.

Read: Ian Athfield honoured with John Britten Black Pin

?Idealog asked three contemporaries to share their memories of the great architect.

Ian ‘Dickie’ Dickson, Director, Athfield Architects

Ian Athfield was a great person and a wonderful architect. He dedicated his life to his family and architecture.

I was privileged to work alongside him over many years and could not have asked for a better friend and colleague. His generosity with his time to assist people and colleagues was incredible. He would never hesitate and enjoyed it immensely.

Everyone at Athfield Architects has learned so much working and listening to Ath. We will all miss him.

Andrew Barclay, Principal, Executive Director and Chairman, Warren and Mahoney

Ian Athfield was one of New Zealand’s unique cultural assets. The cultural circumstances that formed him were particular to his time and place, and like Ath himself, cannot be repeated, emulated or imitated.

In the 1960s, 1970s and 1990s in particular, New Zealand was on a search for its own identity and Ath confidently steered a new path, exploring what it meant to be a New Zealander free from the British mother ship.

His work was a mirror to Ath’s personality – complex, direct, sometimes irreverent and very often beautiful, Ath’s life and work has moved an entire nation perceptively towards a clearer appreciation of its self and its own potential. He was a world class architect and a world class personality. We will miss him.

Richard Harris, Principal, Jasmax?

I knew Sir Ian Athfield (Ath) through the profession of architecture – we worked together when Jasmax and Athfield Architects collaborated on a proposal for a major building in Auckland; I succeeded him as president of the NZIA; and I was Master of Ceremonies at Athfield Architects 40th anniversary in Wellington. In short I was a colleague and a friend.

What defined Ath was his passion for architecture. He had a contagious enthusiasm and a strong belief in architecture as a civilising force that had the power to shape communities for the better. He demonstrated a lifetime commitment to architecture’s public face – to its urban realm, the streets we live in, our small communities, our larger urban centres and the rural New Zealand that we love.

But for Ath it was not just about the architecture and urban form, it was about the inhabitants and communities who occupy that built environment.

Ath always trod a different path. While his work was highly accomplished it was also often provocative. He exploded onto the scene with his residential work in the late sixties and early seventies, with types of residential developments that New Zealand hadn’t seen before. Both his apartments and his single houses had in common forms that were derivative of Mediterranean villages – complex in form and highly engaging, they were designed to encourage social interaction.

He gained worldwide exposure in 1976, when he won the international competition for a United Nations-sponsored, low-cost housing project. Long-haired and bearded he was a contrasting image to the immaculate Imelda Marcos who presented him with the prize. In an effort to determine what was happening on the project, Ath made a return trip in 1977. This was recorded on Sam Neil’s 1977 film, Athfield Architects.

Ath’s work has left an indelible image on the retina of our society, including:

His own house tumbling down the Wellington hillside;

The Don Buck house set among the vines of Te Mata Estate;

Sam Neill’s Queenstown home;

Wellington Civic Square;

Wellington Library (he redefined libraries as living rooms for the city);

Telecom House in Wellington;

Adam Art Gallery, which showed how to make use of a challenging site;

Alteration to the State Insurance building in Wellington, which showed a new way of engaging with heritage buildings without resorting to imitation and replication;

Christchurch Civic Building and Selwyn District Council;

Mixed Use projects, including Wellington’s Chews Lane and the Overseas Passenger Terminal;

And the New Zealand War Memorial London – in collaboration with Paul Dibble and Jon Rennie.

He was among the first to enter into areas which New Zealand architects had previously shunned. For him, urban design was not primarily a site for architectural performance, but rather a social endeavour. It is impossible to separate Athfield the person from Athfield the architect. He was complex, socially-oriented and thoroughly engaging.

He also influenced and helped educate a public audience that has grown increasingly sophisticated in its understanding of the role of the built environment in shaping communities, as well as a generation of New Zealand architects, through consistently producing the best buildings and complexes in the country.

He mentored numerous architects both in New Zealand and Australia through a number of architectural masterclasses, held at his seaside property at Awaroa.

{% gallery ‘christchurch-civic-building-winner-2012-supreme-co’ %}

He and his practice have won numerous awards in a highly competitive profession while at the same time remaining a friend to all and collaborator with many.

People coalesced around Ath because of his ability to inspire, influence and lead; he combined an extraordinary talent as an architect with an intuitively strong business sense and a passion for the giving back to the profession and the public.

His legacy will continue through the many ways in which he has touched our lives.