Originally published August 12, 2015: Peter Beck, CEO of commercial space race leader Rocket Lab, says he can send your satellite into space for just US$50,000 (NZ$76,000), and just as easily as booking an airline ticket. Space, it seems, is now open for business.

It’s not often your boyhood dream comes true in your own backyard, especially if your dream is to blast rockets into space. Think of such things and your mind probably goes to Nasa or Russia or perhaps one of those barren-looking launch pads in a dusty Middle-Eastern landscape. Or Thunderbirds and their mysterious tropical island.

But the stars have turned favourably for Southlander and rocket enthusiast Peter Beck.

“If the best place in the world to launch rockets was in the middle of a desert that’s where I’d be – it’s that simple. But it turns out that launching satellites into space is best done from right here, in New Zealand.”

Now that is a happy coincidence, because the Kiwi rocket pioneer, who has attracted global investment into what seems like a hare-brained scheme, wants to do just one thing: launch rockets and lots of them. Always has.

Soon we’ll know exactly where his company Rocketlab plans to build its launch facility. The best guesses are somewhere remote in the South Island. On reflection, it’s an obvious location.

“When we shoot, there’s nothing there: no air traffic, no population, no shipping, just nothing. In America, if you said you wanted to launch a satellite once a week they’d laugh at you because there’s shipping, there’s a ton of flights, there’s people, there’s everything everywhere. So New Zealand’s only advantage of being a small island nation in the middle of nowhere is if you want to launch rockets. It’s perfect!”

Perfect wasn’t always how Beck described it. When he packed his bags in 2007 for the trip of a lifetime to Nasa and Lockheed Martin he discovered not the labs of his boyhood dreams but an industry moribund in bureaucracy and spiralling costs. “I started talking to these guys and they go ‘You don’t want to work here’. I realised that I was just going to be a tiny gear in a giant bureaucratic machine. And even if I made it really really big in one of these organisations then I was still not going to do what I wanted – launch rockets.”

Depressed, he caught a plane home. “I was, like, ‘Wow, this is my childhood dream and it’s just not panning out’.”

But they make kids tough in Southland. And disobedient too. Aboard the flight, he Googled a company name and designed a logo and registered his company as soon as he landed. “About six months later I quit my job and started Rocketlab and that was that.”

He makes it sound so easy. By the end of this year, Beck plans to send his first payload into space, just the second non-government funded company ever to do so. After that, he says, there are 30 or so customers lined up to launch their small satellites. Plans are for one launch a month in 2016, and then one a week in 2017. The company claims it will eventually handle 100 launches a year.

“Space is open for business,” Beck says. And at $US5 million a shot, business could be a blast.

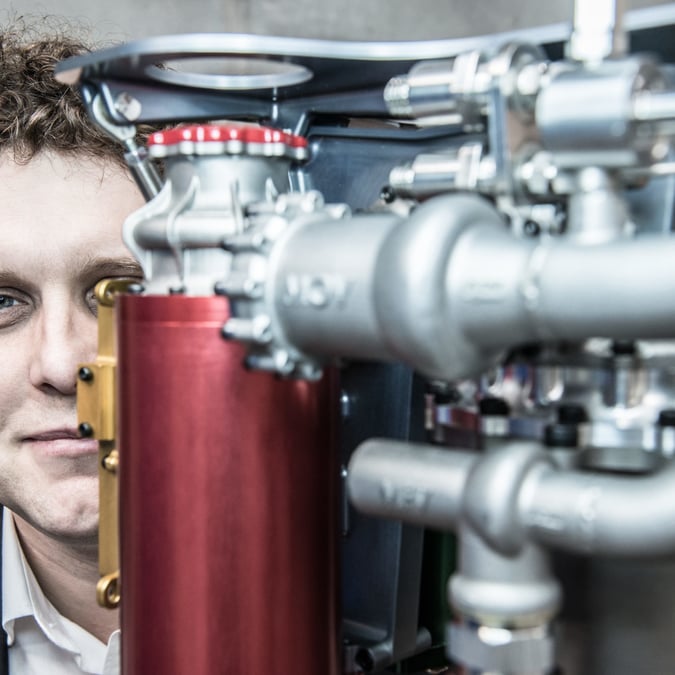

Image: Central to Rocketlab’s success is the innovation in engine technology and carbon-fibre construction. If it’s hard to believe this sort of thing happens in New Zealand, look back: Beck’s knowledge of materials technology was honed at IRL, the sleepy Crown Research Institute, now part of Callaghan.

MISSION POSSIBLE

With his cherub-like face, frizzy hair and uninterruptable patter, Beck ticks all the boxes of the mad scientist. Plus there’s the impatience of a man on a mission.

People just don’t look up enough, he rails. “I’m constantly surprised at how little people understand where they live. They might say ‘I live in this suburb in this city and in this country’ but nobody thinks of themselves as living in a solar system. If you ask the average person to name the planets, they can’t. I mean, can you?”

It sounds like a test so I rattle off all the planets I can remember (“Pluto’s not a planet, it’s a ball of ice!” I say, remembering something from the news) and Beck looks slightly disappointed. “Okay so you might know more than most, though you got the order wrong.”

Space matters. And it has mattered a long time for the 38-year-old.

Beck built his own telescope as a child, following the example of his father Russell, who constructed a large telescope for the Southland museum when he was just 18 (it’s still in use). Russell later became the museum director and Peter remembers “at about six or seven going to stuffy old Astronomical Society meetings at the museum where you’ve got all these boffins sitting around drinking tea talking about space and telescopes. A lot of these guys had PhDs and really knew their stuff. I found it absolutely fascinating and probably understood 5% of what was being said. But I was hooked.”

All that talk could have made Beck an academic but he got his hands dirty in the family workshop, carrying on a passion that started with his grandfather who would lend tools to another famous Southland tinkerer, Burt Munro of The World’s Fastest Indian fame. “Burt used to come into my grandfather’s workshop and use his equipment and make a hell of a mess and leave,” Beck says.

Engineering runs in the family. Before the museum Peter’s dad, Russell, was an engineer. Peter’s middle brother Andrew is a mechanical engineer and electrician; his oldest brother John runs a caryard by day and is a competitive motorcyclist in the weekend. Cousin David still runs Beck Industries, the engineering shop set up by Peter’s uncle Doug. Their speciality: outdoor vacuum cleaners.

The family garage was where the boys built go-karts and then, in their teenage years, souped up their Minis. “They all modified our Minis,” recalls Russell. “They’re easy to work on and actually pretty much anything you do improves them. Peter was determined to make his go faster.”

“It’s always been about the rocket, there’s never been a question really – even at high school. I remember I failed a careers assessment test and they needed to talk to my parents about it. I was so defined about what I wanted to do and the test didn’t allow for that.”

The trend continued at James Hargest College in Invercargill, where the metalwork teacher “threw him the keys to the workshop” (says David) and then at Dunedin’s Fisher & Paykel, where he completed a tool-making apprenticeship and learned (says Russell) “how to combine engineering and design. He’s very precise – everything always has to work and look good, with Peter.”

It’s also where, in 2000, with generous help from his colleagues at F&P, he built a rocket-powered bicycle that he demonstrated to the bemused public with a 140 kph blast down Dunedin’s Princes Street.

“At F&P they would give me lumps of titanium and just write them off as apprentice-training projects. I’d build my rockets at night using their workshops. And when I moved into a design role I did simulations on rocket nozzles, optimising the flow for rocket fuels.”

Next, Beck landed a job at Industrial Research Ltd in Parnell, Auckland (now merged into Callaghan Innovation), where he developed a deep understanding of metals and their strengths, and learned how to test his ideas. And his rockets. As at F&P, IRL managers turned a beneficent blind eye to his after-hours experiments.

“It’s always been about the rocket, there’s never been a question really – even at high school. I remember I failed a careers assessment test and they needed to talk to my parents about it. I was so defined about what I wanted to do and the test didn’t allow for that.”

ROCKET MAD

“Stick to the day job,” the joke goes. That’s good advice for most of us. But when Beck quit his job he attracted more than the usual bunch of family and fools.

“Lots of people have passion for things and don’t follow through. Peter’s passion is rockets – but he’s also got the engineering skills. He can see it through.”

That’s Alan Johnston, the building manager of IRL’s Balfour St premises, who shoulder-tapped the young entrepreneur to occupy empty space on the second floor. “There weren’t many places in Auckland that young entrepreneurs could go for this kind of hi-tech manufacturing. So I charged him a low rent and allowed him to use the equipment, especially the labs. I didn’t really ask permission from HQ. It just seemed like the right thing to do.”

Another early supporter was Mark Rocket, the internet entrepreneur and space-nut who changed his name by deed poll from Mark Stevens and received media coverage as the first Kiwi to join Virgin Galactic’s space tourism programme. Beck approached Rocket and the two hit it off, with the latter adding seed capital and becoming a 50% owner until he exited in 2011.

“Everyone is rooting for us. I think it’s very Kiwi that no matter who we talk to, everybody is rooting for us and wants us to succeed. And you know, we talked to Civil Aviation and they bent over backwards to help us. We talked to central Government and they’ve always bent over backwards and helped us.”

“We had a similar vision,” says Rocket. “We believe a space industry can emerge from New Zealand. In those first four years we worked hard to solve really difficult problems. But Peter’s got a lot of determination and the ability to overcome technical hurdles.”

The pair attracted another curious supporter, Sir Michael Fay, the merchant banker infamous for his involvement in a 1990s scandal known as the Wine Box enquiry. Fay’s name, long vanished from the press, emerged like a blast from the past when he provided his Great Mercury Island for a maiden test flight.

“We asked Sir Michael if we could launch off his island, and he just said ‘anything you need, you’ve got’,” recalls Beck. “And he gave us his helicopters, barges, house, chef – everything was ours. Every time we’ve launched out at Great Mercury Island, it’s always been the way. We’ve done a number of really, really important demonstration launches to really important people and, you know Michael’s helicopter comes and picks them up and there’s food laid on, there’s everything.”

The support extended beyond individuals. “Everyone is rooting for us. I think it’s very Kiwi that no matter who we talk to, everybody is rooting for us and wants us to succeed. And you know, we talked to Civil Aviation and they bent over backwards to help us. We talked to central Government and they’ve always bent over backwards and helped us.”

I suggest that it’s unusual, this kind of support.

“Really?” Beck asks. “Well, it’s the honest truth and anywhere from the mayors of the cities where we’re trying to build launch sites, to well anybody. We’ve never ever hit a brick wall from any regulators or people in power.”

The support came to a dramatic, and media-propelled, climax at 2:28pm on November 30, 2009, when TV3 broadcast the maiden flight of Atea 1, Rocketlab’s prototype rocket. After technical delays (including a dash to a local mechanic) Atea, also named Manu Karere, blasted into a clear sky.

“It was an amazing sight and sound to behold,” wrote Mark Rocket in 2011. “The rocket flew beautifully and powerfully into the sky, the throaty roar of the hybrid rocket engine reverberating over the island. The spectators were elated and tears of joy erupted. Some were crying from the drama of the day’s events and the profoundness of the experience.”

Beck can be seen leaping and yelling like a loon on the TV footage.

UNDER WRAPS

The nice lady at the Rocketlab reception says I can’t carry my cell-phone in the building. “Top secret,” she says. “But take a seat, there’s a new Woman’s Day there.”

Six years after that initial launch, and the bland, concrete office near Auckland’s airport hardly looks like the HQ of a pioneering satellite company. I imagine that in the US, something like Rocketlab would be barricaded with heavy fences and heavier guards. A reporter from a no-name magazine would certainly have trouble getting access to its boss. In New Zealand you just pick up the phone.

It makes Rocketlab’s success all the more remarkable.

With just three staff at the time (2010), Rocketlab won contracts with international firms for aerospace work. In particular from DARPA, the US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, which is attributed with the invention of technologies such as GPS, the CDMA cell phone network and Apranet, the precursor of the internet. Beck won’t say what Rocketlab worked on, but the money flowed and the credibility built, along with the staff.

“By 2011, I sort of felt that we’d reached the point where we had enough credibility within the industry to do what I really wanted. It was kind of a crossroads, because we could have gone down the aerospace contractor road but I’m absolutely negatively inspired by doing that.”

So he hit the drawing board again and laid plans for Electron, the rocket that he hopes will underpin the launch business.

Again, the tributes and support flowed. “I was inspired by his audacity,” says Warehouse founder Stephen Tindall, whose K1W1 fund invested in October 2013, along with the Government’s Callaghan Innovation.

Also inspired was Vinod Khosla, co-founder of Sun Microsystems and one of Silicon Valley’s most respected venture capitalists. Khosla’s investment provided not just much-needed capital, but global credibility.

“We were kind of lucky with Khosla in the fact that they had previously invested in [micro-satellite Company] Sky Box, sold last year to Google. So they had experienced firsthand the issues of getting a small satellite in orbit. Launch is the single hardest thing for small satellite companies.”

There are dozens of satellite launches every year but what appealed to Khosla was the new approach to an old problem. So far most of the commercial effort has gone into satellite technology, with only a handful of companies, including Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic, reinventing launch. “What’s normally done in this industry is that you take a heritage Russian rocket motor from here, and a heritage tank from over there, and you put them all together. But to start from scratch and assume there are no constraints is a new approach.”

In that sense, the New Zealand-ness is part of Rocketlab’s success. A country with no heritage in space is exactly where you’d expect ground-breaking innovation to come from. Khosla’s other investments in New Zealand are similar outliers: Lanzatech, the waste-to-energy company started by Sean Simpson, and Biodiscovery NZ, a biotech company extracting plant microbes.

Rocketlab’s solution, the Electron, is novel. The combination of a carbon-fibre, recoverable rocket, a dual electric/dry fuel engine, secret-sauce electronics and an end-to-end launch facility in New Zealand means Beck reckons he can slash the price of launch from about $US130 million to $US4.9 million. That saving means the much-hyped shift from government-dominated space travel to industry-led might finally happen.

The Electron keeps winning impressive support. In March this year, Rocketlab conducted its second formal funding round, Series B, convincing Khosla and K1W1 to reinvest. It also added two industry heavyweights: Bessemer Venture Partners, one the oldest venture capital firms in the world (and the money men behind global success stories such as Staples, International Paper, Skype and Shopify); and Lockheed Martin, major supplier to military and space programmes.

Image: Image: On board: Beck has won more than a sympathy vote, securing millions in funding from backers such as Khosla Ventures, Lockheed Martin, BVP and Stephen Tindall’s K1W1. “I was inspired by his audacity,” says Tindall (pictured with Beck, above (left)).

“Rocketab’s work could have application in a number of aerospace domains and we look forward to working with them to complement our overall efforts in small lift capabilities and hypersonic flight technologies,” says Lockheed’s press release.

Beck believes the investment comes because the market is ready. “In the next decade you’re going to see space change from being a government-controlled domain, to commercial. It’s government railroad versus FedEx vans. It’s just awesome.”

But the support also reflects a ridiculous dream. From its early days as a cheap tenant in Balfour Street to its current 50 or so international staff, Rocketlab is a testament to Beck’s passion and skill – and a textbook example of how it takes a village to raise a child.

From a grandfather who encouraged play in his workshop, to tolerant employers and enthusiastic amateurs giving money, helicopters, media crews and chefs, the journey to space from Aotearoa might be one for us all to claim as our own.

Watch this space.