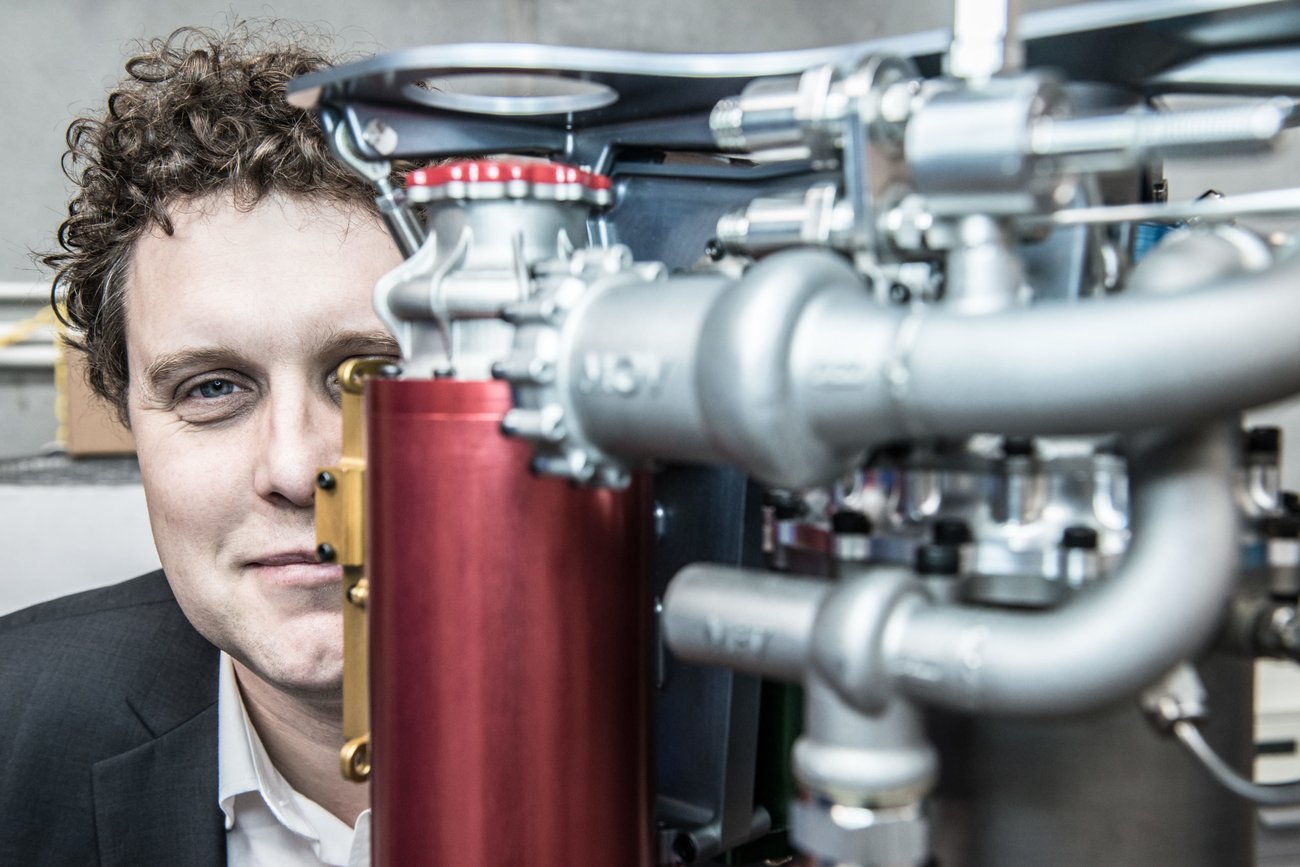

New heights, new depths: Rocket Lab’s Peter Beck on the future of space exploration

Read the first part of this series here.

While James Cameron is residing in New Zealand for six months of the year as he works on the upcoming Avatar films in Wellington (just 15 minutes by helicopter from his Featherston home, he says), he was born and bred in the US. Luckily, we have many of our own homegrown explorers to call our own – and one whose sights are firmly fixed on a frontier outside planet Earth is Rocket Lab’s Peter Beck.

Like Cameron, he has also potentially put his life in jeopardy to experiment and innovate. His desire to build rockets was so strong that in 2000, while working at Fisher & Paykel with the help of some colleagues, he built a rocket-powered bicycle that he demonstrated to the amused public with a 140 kilometre blast down Dunedin’s Princes St.

But following the usual avenues into space exploration wasn’t for him. When he finally got his crack at fulfilling a boyhood dream of going to work for NASA and Lockheed Martin in the US, he was disappointed to discover an industry that was cloaked in bureaucracy and restrictions.

“I started talking to these guys and they go ‘You don’t want to work here’,” Beck previously told Idealog. “I realised that I was just going to be a tiny gear in a giant bureaucratic machine. And even if I made it really, really big in one of these organisations, then I was still not going to do what I wanted – launch rockets.”

On his flight home, he checked to see if Rocket Lab was taken, registered it and went out on his own. Beck’s bold plan? Democratising space through affordable 3D-printed, battery-powered rockets that can send small satellites up into space at a far more frequent rate than what had been seen before.

That cost reduction, for contrast: in 2016, the US went to space 21 times and the average cost of a mission was $221 million. Rocket Lab’s goal was to launch one rocket per week from just $8.2 million.

Beck’s tale of Kiwi ingenuity has been told in Silicon Valley boardrooms and proudly at New Zealand awards nights. And since the day Rocket Lab opened for business, the company has had one failed launch in 2017 (the rocket was named ‘It’s a Test’) and one successful lift off on January 21, with its Electron rocket (called ‘Still Testing’) taking off from Rocket Lab’s Launch Complex 1 on the M?hia Peninsula in New Zealand at 2:43pm local time.

It reached orbit some eight minutes later and successfully deployed its payload of three satellites – as well as an undisclosed satellite called the Humanity Star. The three-foot-wide carbon fibre sphere made up of 65 panels reflecting the sun’s light made headlines around the world and was meant to create a shared experience for humankind, who can look up and marvel at the night’s sky. It caused quite a ruckus in national media, with some praising it, some calling it a stunt and several astrologists saying the light pollution was the intergalactic version of graffiti (they needn’t have worried, as it fell out of orbit and was destroyed just two months later).

Such feats are all in a day’s work for Beck, who is living out his dream of building rockets every day – and he says the industry is just getting started, as there is no holds barred now that fledgling companies can enter the game.

“It’s an incredible time for the space industry at the moment, as no longer do you have to be government to be able to do anything meaningful – or even a large organisation,” he says. “There are tonnes of small companies having disruptive effects on the industry and we’re right at the beginning of the industry with respect to commercial influence and you see that all around the world.

“In Silicon Valley, there’s been a billion dollars invested in space start-ups. There’s huge potential and it’s one of those things that is geographically agnostic, it doesn’t matter where you do that from – New Zealand or Silicon Valley. You don’t need any reserves or resources other than bright people. New Zealand has a really exciting future there within the space industry.”

Rocket Lab now has the aforementioned M?hia Peninsula site, which is the world’s only private launch site (located on the North Island’s East coast), as well as two sites in the US: Cape Canaveral in Florida and Pacific Spaceport Complex in Alaska. It also raised US$75 million in venture funding last year.

According to a recent report from US-based investment firm Space Angels, investors put a record US$3.9 billion into commercial space companies in 2017.

As well as this, the company reports that over the last eight years, investors and founders have made US$25 billion in exits following acquisitions and public offerings, said Space Angels. It counts 303 companies in the space sector globally. And according to Kevin Jenkins of professional service firm MartinJenkins, in 2018, there are now around 70 different space-related businesses and other entities in New Zealand.

In Silicon Valley, there’s been a billion dollars invested in space start-ups. There’s huge potential and it’s one of those things that is geographically agnostic, it doesn’t matter where you do that from – New Zealand or Silicon Valley. You don’t need any reserves or resources other than bright people.

So apart from the commercial opportunities, what excites Beck the most about the frontier of space? For one, it’s not the actual rocket taking off – although that is a visual marvel in itself. It’s what happens after lift-off.

He says despite all the advancements in humankind’s history – moon landings, Mars mappings and more – the possibilities for what can be accomplished in space are yet to be fully realised, as well as the effect these developments can have on our day-to-day lives, businesses and resources.

“Think of the internet when we’d just begun. All you did was send an email, right? If you went back to that time and looked at the things the internet was going to enable, it’s the same with space. We’ve literally sent our first email – that’s where we’re at,” he says.

“The biggest thing that’s going to be done in space and that we’re all going to look back on is yet to be done. There’s a huge opportunity for Rocket Lab and for mankind.”

He says a few of these developments are already in the process of occurring, such as internet from space.

“That’s going to disseminate the internet to every single person on this planet, and for a developing nation, that’s useful,” he says. “You can go take university courses online and it doesn’t matter if you live in a mud hut. As a species, that’s very transformational.”

Another example is weather satellites, which can provide life-saving data on natural disasters, such as a cyclone barrelling towards the coast of New Zealand.

“America has 30 weather satellites as a country,” Beck says. “With climate change, what happens if you have 30,000 watching the weather? What happens if you turn them out to look into the cosmos? It’s an incredibly disruptive time within the industry and we’re going to see amazing things.”

So what’s stopping our appetite for exploration? One factor holding us back might be that although New Zealand prides itself on producing world-class innovators like Beck, culturally, we can hinder ourselves when it comes to opening up new industries and cashing in on them.

Beck says New Zealanders can often have an incredulous attitude to what can be accomplished.

“I was very open in the fact that my intention was to build a large billion-dollar-organisation and be the best at delivering small spacecraft to orbit,” Beck says. “It always amazed me – I get that people would have scepticism about the space bit – but that they would also have scepticism about building a billion-dollar-company.”

New Zealand needs to scale its ideas in what it wants to achieve to be bigger, he says – not from an innovation standpoint, because we do tend to have a lot of great ideas, but about how far we can take them and how much they’re worth. Besides, with a glass ceiling overtop of great ideas, how can anyone aim for the stars – or send a Humanity Star up into space, for that matter?

“I think that it is drawn into deep culture here in New Zealand,” Beck says. “When I go to start-up events and listen to entrepreneurs talk, they talk about how they can’t wait to make their first million, while the same group of entrepreneurs in America are talking about how they can’t wait to make their first billion. There’s a scale issue and a cultural shift that needs to occur.”

And the other issue holding us back from breaking new ground in areas like the space sector? Venture capital.

“Let’s not beat around the bush – in New Zealand, there is no venture capital community here,” Beck says. “You’ve got folks like Steven Tindall trying to make a difference and doing a good job, but apart from that, the venture capital industry in New Zealand is shocking. I’ve seen so many good companies destroyed by VC, as they’re not providing what good VC does well: recommendations, information, knowledge, and the ability to reach out to a new network.”

Think of the internet when we’d just begun. All you did was send an email, right? If you went back to that time and looked at the things the internet was going to enable, it’s the same with space. We’ve literally sent our first email – that’s where we’re at.

Plus, when a company does eventually move offshore in search of the money, he says it becomes a case of lamenting ‘we lost another one’ instead of celebrating the success of a New Zealand company that’s gone global.

His advice to entrepreneurs and explorers like himself that are on the verge of a new frontier is to first and foremost, set the company up for global success, so the rest will come easy.

“It’s about bringing in incredibly knowledgeable, well-connected capital, capital that’s used to building large organisations and that can pick up the phone and call anyone on the planet you need to talk to,” he says.

As for New Zealand’s burgeoning space industry, it seems it’s just getting started. Beck says there’s opportunity for new space research, infrastructure and analysis alongside launches, while developments in this area will have applications for other industries too, such as agri-tech, climate change modelling, oceanography and structural planning.

But perhaps most interestingly, the space sector has a unique advantage. Unlike tech companies in other industries that have forged ahead of rules and regulation, causing the law to have to make amends and play catch-up (think Uber and Airbnb), when Rocket Lab was founded, there was no space regulatory regime in New Zealand to work off.

The company played a part in helping the government draw it up from scratch, meaning it is future-proofed for decades to come – and it’s especially designed to not only manage associated risks and ensure New Zealand meets its treaty obligations with the US, but to also encourage the innovation and development of a New Zealand space industry.

It’s even in the title, Beck says.

“That’s no better title than ‘to grow and regulate’ a space industry – usually the framework would just be to regulate a space industry. It’s a very unique position for New Zealand to be in.”