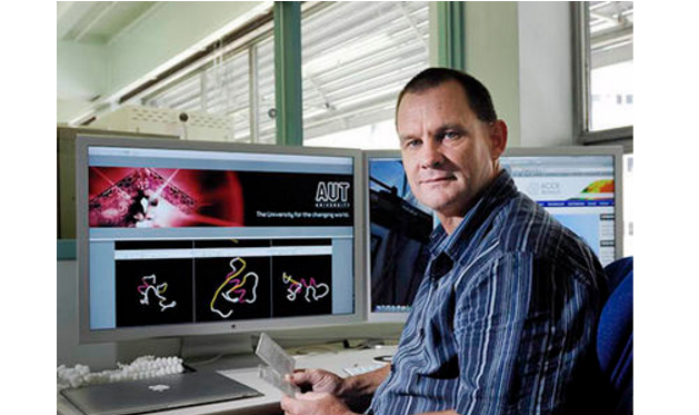

Vodafone xone Innovators Series: Kode Biotech’s Stephen Henry about platform innovation

Henry Oliver: How do you tell a layperson in 30 seconds what Kode Biotech is?

Steve Henry: Kode Biotech is a company, explaining code technology to them can’t be done in 30 seconds. (laughs)

90?

90 seconds. It’s very possible. Kode Technology is a cell surface modification technology. It’s a biological paint that can change surfaces to do different things.

What things can it do?

It can do many, many things. It can modify cancer cells to teach the body to recognize it. It can be a diagnostic marker that can make antibodies react with it. What can go all the way up through to anti-counterfeiting constructs for prevention of fraud right through to treating babies against disease.

Where did the idea for Kode Technology come from?

Kode Technology was based on a fairly long academic career working on a molecule that had an ability to hop into cells. It was a blood grouping molecule that was first known in the early 50’s, and nobody had any interest in this molecule. I studied it for many, many years. A couple of PhD’s later, I knew a little bit about this molecule. Then I started to think well maybe I could make it actually do something very useful. Then started my innovation pathway of actually changing a natural molecule into a man-made version that could actually do a lot of different things.

What was the first thing you made it do?

The very first thing we made it do, and essentially a commercial product in the market is we added ABO blood group system molecules onto the outside of blood cells. This has been used in Australia for quality control systems.

What made you realize that you could turn that technology into a business?

The driver to turn it into a business was actually not the motivation around that. The motivation was how hard it was as an academic in those days to raise research funding. The inability to raise research funding made me think about, “Is there a different way to fund my research?” I thought, “Well actually, if I do research that is commercially interesting and commercially viable, then that would be a route to take.” Interestingly enough, later on I came to realize that actually it’s a really good way to do research. If it gets made, then it actually has real use and utility, and people want to have it. Now it’s my major driver the way I do research.

What sort of decisions or sacrifices do you have to make to turn it into a business? Did you stop teaching? Did you have to re-mortgage your house?

Well two wives later! Look, it’s a really, really tough journey. What motivated me to do it is I guess I was born to do what I do. It was not a driver for me of making money. The fact is you don’t have any money during this process. I live on virtually nothing for many, many years. Not having money doesn’t get in your way of wanting to do an innovation or take something through. Yeah.

Were there any early roadblocks that slowed you down?

The whole journey is full of roadblocks. You just don’t think about roadblocks as being something that you can’t climb over. Yeah. Every step of the way is a roadblock. If you’re worried about roadblocks, then you shouldn’t be on the road. You just get a big enough truck to drive right through the roadblock, or a way to find a way around them. Roadblocks are normal. They’re not a problem. They don’t block you.

Right. Were there any significant failures?

Research is 99% failure. We learned more. We know many, many more ways how not to do it. Knowing how not to do it is actually a success. Every roadblock, every failure tells us a better way, or we learn from it of a way to go forward. Yeah. It’s mostly failure, and a few successes. When you get successes, the successes have to be valuable enough to outweigh the failures.

That’s part of the scientific method. Many failures, learning from those failures. Did that help you on the business side? Did the scales from the science side transfer into the business side? You’re the founder, but you’re also the CEO.

Generally, science skills get in the way of doing business. You have to be a bit more brutal in a business setting. You have to know when you should not be doing a project just because it’s interesting. In business, if it’s a project that is interesting, and it’s not going to make money, you’ve got to be able to kill it. Scientists generally don’t like killing projects that are really, really cool and interesting just because they’re not going to make money. There is a disconnect between the business and the science side of things.

The science disciplines that I’ve brought into business that I think have been absolutely critical for where we’re at today, is the pure honesty of real science. You tell it exactly how it is. You don’t actually over market it. It’s something that sometimes doesn’t connect with a lot of businesses.

What’s the key thing that you know now that would have made the biggest difference for your journey along the way?

Experience. Unfortunately, it is a journey. You need the journey to get the experience to be able to do a base-up. You can’t start off with it experience until you’ve got all the battle scars. However, what you do you learn during the process. You’ve got to have them placed very early, is mechanisms to survive. Provided you can survive the journey, then you’ll be fine on it.

What’s the experience you’ve had with Kode Biotech that you’d reflect on, or give advice to someone who has a great idea, and wants to turn it into a business?

This might be a surprising answer, but the most important thing is learning how to communicate your project, your science idea to people. If you can’t communicate it well, you won’t get the uptake. You’ve got to get uptake for things to drive across. Unfortunately, communication is for engineers and scientists generally something we’re not very good at. However, those are critical skills that you need to develop. Usually, you don’t have the money to be able to buy those skills until you’ve made a lot of money, so you have to try and develop them. It’s something that even today is still one of my primary drivers, learning how to communicate our technology better. Every time we do this better, we actually get a significant increase in business for the company.

You came out of your academic research, and it partially remains within an academic institution. Is that right?

Kode Biotech is a little bit different. Kode Biotech is a spin-in company. It was actually developed outside of the university on the background of my university education done overseas. Then I was fortunate enough to be able to set it up within the AUT University infrastructure, and that’s provided us with the support mechanisms to actually grow this as a company.

Right. You operate within AUT’s facility obviously?

Yup.

You have support from them, yet you’re an entity within yourself?

Kode Biotech is a separate commercial entity which lives on the premises of AUT University. I’m a Professor within the School of Engineering from a business perspective side of things. And I am also also CEO of Kode Biotech simultaneously. This is an unusual integration of a business. A real business doing real things in an academic environment. The value of that is the students get exposure to real world activity, and we get exposure to real academic activity in resources of the infrastructure of the university. It’s the most beautiful symbiotic relationship that I’ve ever been involved in. It just works really well.

Tell me more about the transition from being a scientist to the head of a company? How did you approach it? Was there a big learning curve for you or was it a natural evolution of your role?

Yeah. The last point is correct. It’s a natural evolution of the role. Most developments, particularly in scientific staff help with very heavy research, and they transition across into very heavy into the commercialization stage. It is a natural evolution of the role. You have to be a person who finds their transition or metamorphosis of yourself into a different person as exciting.

To sell science, you really need to understand science. Bringing in a pure business person to sell a scientific technology without any real science background, they would miss a huge amount of opportunities. However, a lot of scientists I know don’t like the business side of things. Personally, I find them both incredibly exciting.

How do you spend your day? Are you in the lab? Are you in meeting rooms? Is there a percentage split?

There’s no percentage split. I have it now. I was originally for the first many years of the company, I was both the Chief Scientific Officer and the CEO as a split role. I now have a CSO who actually takes that scientific role, and relieves me of it so I can concentrate more on the commercialization aspects. I probably still have a total oversight of all the technology, and on the core of every part of the technology at the moment.

My mornings start at 6 am. I’m an early riser. That’s behind my desk at 6 am here at AUT. Probably after lunch time, I concentrate on all commercialization aspects. That’s teleconferences with Big Pharma companies, and trying to stitch together deals with commercial opportunities for the team. Usually in the afternoon, I go across to the lab. Then I’m working with the scientists over there, and with the team. They come over to here, into my office, and we split between them. It’s a mix of them. I still stay very intimately involved in the science, but the key driver for me is the commercialization aspects of it.

The application that got a lot of attention last year particularly the Innovation Awards was the Agalimmune cancer treatment. What’s happened since then? Are there any other commercialization routes that you can talk about? How are other people using your technology?

Yes. One of the problems we have is the people we work with. We sub-sell our products to big pharmaceutical companies who use it within what they’re doing, etc. they generally don’t want us to tell anybody what we’re working with. I can tell you right now we have 2 separate projects, major major projects with a Pharma in the top 5 Pharma in the world. I can’t tell you any more than that.

However, that’s just an aspect of it. In fact, I’ve had 2 separate telecoms with this major Pharma just this week. We have at least 6 or 7 other major projects that are simultaneously running with commercialization opportunities out there. That’s what keeps me occupied in my mornings.

You’ve got an interesting business model where you have the base technology, and then you license that base technology for other people to build upon. Is that how you sum it up?

That’s correct. Kode Technology is a huge platform. It’s way, way too big for us to be able to chase all those opportunities ourselves. What we decided very early on is the best way is to collaborate, and use all the other people to actually take out products, or take our ideas through to products. We control the intellectual property, and we enable others to use it and develop new generations of products that they will then take to market. We license them to use our technology. Some of the ideas that other people are coming out with the use of our technology are really, really cool. We’ve always said our best ideas will come from other people.

I’ll give you one beautiful example for that. The one that we’re most famous for we had virtually nothing to do with. The Agalimmune product, we’re using our molecules to inject it into tumors to teach your body to attack it. We didn’t know anything about that project until they came to us, and asked us could we make them a paint to do this? They had already developed the ideas. They’d already been using our molecules which they had been buying from our R&D supplier and they found they worked really well.

By making our paint scent, or our technology available to the larger community enabled other people to come up with the cool ideas. We’re just a service in many respects. We lay down the foundation of “This is what it could possibly do.” Hopefully people will say, “Wow!” Pick up the old idea, and go and do it themselves. That’s exactly what’s happening.

I’m hoping that we will have 100 to 1000 different people with different products in the next 5 years.

Are they getting small amounts, non-commercial amounts of your technology to then build on?

Oh, they buy small amounts of products from us to develop their own products, and their own R & D. For us, it’s very cost neutral on the R & D. The research and development that we do here at AUT is of around developing the next generation of products that we can put in front of the different players. There is hundreds of different variations of our paints that can do thousands of different things.

Communication of this is one of our major drivers. We try to educate the research community and all the different universities. There’s some very major universities using this technology out there for them to develop whole new ranges of opportunities.

We’ve talked before about the difficulty of explaining science in the media in particular. What do people get wrong about Kode? What’s the biggest misunderstanding that you’d like to set straight?

What’s the biggest misunderstanding? That’s a really interesting question.

Too many?

The biggest misunderstanding is … I need to turn it the other way around. Kode Technology is so simple to use that it is too good to be true. To apply Kode technology onto a surface, we just put it on their surface and leave it on there for a second, and that’s the entire process. You put a normal scientific method in place, you would spend days, or weeks, or even months trying to bring about what we can do in a few seconds. Our biggest problem we have is that it’s so simple to use. It requires absolutely no skill to be able to use it. You just simply add 2 things together, and it does it so fast in seconds or minutes. It is so good. It is too good to be true. This has been our major problem of communication. This really does these things. It really does them … a monkey could do them. That is one of the big problems. It’s an incredibly weird problem to have when something is actually too good to be true. Yeah. It’s a real problem.

That’s a good problem to have.

I prefer not to have it as a problem. That’s what we’re working so actively around communication to try and overcome this problem to get a much larger uptake over it.