Vodafone xone Innovators Series: AJ Hackett on stretching minds, pushing limits and jumping nude

Originally published November 11, 2016: To mark the arrival of the Vodafone xone business accelerator, Idealog is interviewing heaps of established New Zealand innovators, as well as the founders of the 10 startups selected by Vodafone to receive mentorship, funding and the potential benefits of working with a global network. In this week’s podcast, publisher and editorial director Ben Fahy talks with AJ Hackett, the co-founder of AJ Hackett Bungy, renowned daredevil and one of the forefathers of New Zealand’s adventure tourism industry.

Ben Fahy, Idealog’s publisher and editorial director: As has been detailed many times, you and your co-founders, Henry van Asch and Chris Allum drew inspiration from a couple of places. The land diving on Pentecost Island in Vanuatu, and from the Dangerous Sports Club, which I think was loosely associated with Oxford University and did the first bungy jump. You were the first to commercialise it. When did you see an opportunity, as a business, and was it planned or did it just happen?

AJ Hackett, co-founder of AJ Hackett Bungy: Well, basically, I had a ski shop in Ohakune with a friend called Chris Allum, and the shop wasn’t doing particularly well, and had a bit of debt. The driver of that was Chris pushing me to go, “AJ, why don’t we charge for a few bungy jumps? I’m sure people would pay for the pleasure”, and I had a great reluctance to do that. In the end, he convinced me, and so we did a couple of jump weekend sessions. One of three days, and another of ten days. On the final one, we raised enough money on that to pay our bills and actually close the business, because it wasn’t in a good way. We decided to move onto more positive things. After that, we actually went down to Queenstown, and Henry and I hooked up there, where we commercialised the Kawarau Bridge, and it’s been running ever since.

You make it sound so easy, AJ. I’m sure it wasn’t. I mean, it sounds quite simple on the surface, a big elastic band strapped to a human being, jumping from somewhere high up. Doesn’t sound like it was that simple, not only because you guys had to experiment on some of the early models and jump off things, which seems quite dangerous, but you also had to a lot of regulatory work to create safety standards for the industry. Did you have many doubters or, even, close calls, and how did you convince those doubters that the idea had legs?

Well, basically, to start with, Ben, we had no intention of ever commercialising it. The idea was just to see whether it could be made predictable or not, and Chris and I discovered within about three weekends that it was actually quite predictable, as long as you knew the height of the structure you were jumping from, the weight of the person, and the size of the rubber band. Once we had that dialed, then it was, really, working with the right crew. Him and I travelled in Europe, we worked together and brought in some mates to help hold ropes and using basic lowering systems, we were able to do it consistently quite safely.

The problem we had was dealing with large numbers of people, and we knew that was actually the biggest challenge, where people just naturally get really excited and they’d start climbing onto the handrails of bridges to get better views. They’d start to forget about the fact that they were a long way above the ground, and they’d be getting tangled up in all of our ropes and equipment. We had to design, first of all, a system that we felt would actually be safe to operate in a public arena, so it was really figuring out how to separate the public from a jump deck and the operators from the public as well, so we could just focus on the job at hand, which was tying people up correctly to the system, putting them in a decent harness and then fitting it, so they could safely jump and be lowered to the ground or raised back up. The jump is not over until the person is back on terra firma.

The outdoors is very much what turned us on in those days. We didn’t have clever phones and video games, and all that sort of thing. We were always up for a challenge, and whether that was climbing trees, or wandering in the bush, or surfing, or building huts, or stealing the neighbours’ fruit off their trees, it was all good, healthy fun. I actually developed a real passion for jumping off cliffs and bridges into water, and as a part of that, it was more fun the higher you went.

With the first two years, we were experimenting on ourselves. Jumping off all sorts of different structures and places around the world. By the time we got to New Zealand to go public, if you like, there was very little regulation about in those days, so it was relatively easy to cut through that side of it, but it was more the challenge of finding a place to do it from. We had a lot of historic footage, and it there had already been quite a lot of media, we already had a reputation … People kind of knew what we were doing. It was really just convincing, in those days, the Department of Conservation, that it could be a good opportunity for them to help restore the old Kawarau Bridge, and so they let us have a go. It proved to be really successful for both DOC and us, and obviously the customers. They had an amazing time, and one thing led to another, and so …

It was actually reasonably simple to start, but then there was an enormous amount of challenges after that, where a lot of people tried to jump on the bandwagon. These people had no experience, so were really high risk to themselves and their jumpers and also indirectly, to us, because we now had a business to run and we didn’t want people getting killed by third parties which could ultimately damage what we were doing in New Zealand, and what our aspirations were offshore.

I guess that’s the beauty of adventure tourism, creating the illusion of danger with safety inherent in that business. What were you like as a child? Did you always have that adventurous, maybe slightly masochistic streak, that you desire to push the boundaries and, maybe, to start something of your own?

Often it’s easier to ask for forgiveness than it is to ask for permission. That was our philosophy from the beginning.

Yeah, well, I think as a lot of young Kiwi kids, the outdoors is very much what turned us on in those days. We didn’t have clever phones and video games, and all that sort of thing. We were always up for a challenge, and whether that was climbing trees, or wandering in the bush, or surfing, or building huts, or stealing the neighbours’ fruit off their trees, it was all good, healthy fun. I actually developed a real passion for jumping off cliffs and bridges into water, and as a part of that, it was more fun the higher you went. There’s a little bit of science in that, making sure the water was deep enough, and there were no obstacles under the water and that when you impacted on the water, you impacted correctly so it didn’t damage yourself too much. I always enjoyed a challenge. Bungy just became something you carried through, really, from childhood.

That luxuriant mullet that you had back in the early days would have protected your head from some falls, I imagine.

That luxuriant mullet that you had back in the early days would have protected your head from some falls, I imagine.

Yeah, yeah. They were always handy.

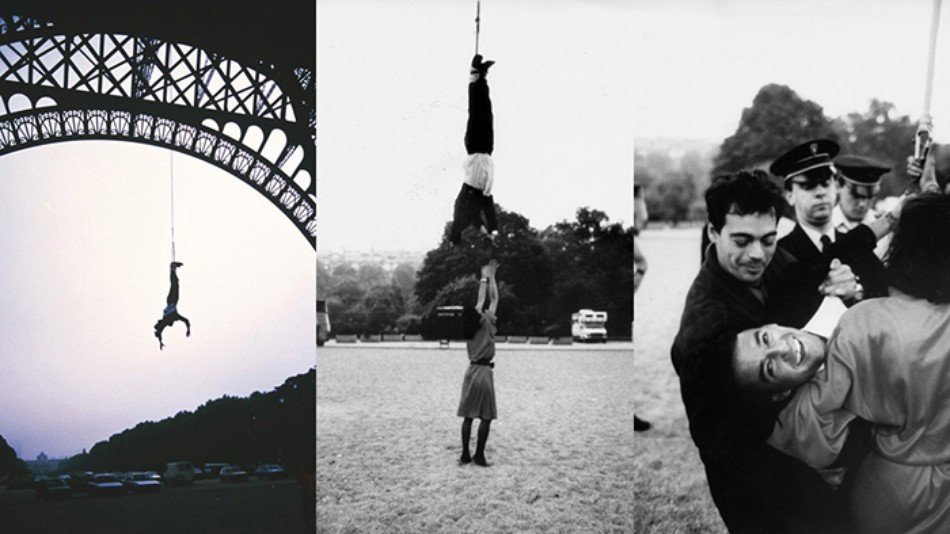

These days, PR stunts are probably a dime a dozen. Over the years, you’ve earned a reputation for being a bit of a loose cannon, and that’s helped the company, I think. It’s been infused into it. You’re ahead of the game on that front, and stretched the legal boundaries from time to time. You jumped off the Eiffel Tower in 1987, famously. Got taken away by police. Not for very long, but … You jumped off all kinds of other things. Bridges, balloons, helicopters, and it all gets covered. How did that media attention help the business grow?

It’s helped it hugely. That’s something that we’ve always been very respectful of, is working closely with the media wherever we can, and that’s normally a really positive story anyway. Everyone has a lot of fun. It’s lovely to see, as a viewer. For us, it was more about just going and doing it … Often it’s easier to ask for forgiveness than it is to ask for permission. That was our philosophy from the beginning. As long as we weren’t damaging anything or vandalising something in order to jump from a structure, then I personally didn’t see a problem with it. We’d just go ahead and do it, and if the police rocked up, our normal reaction would be to say, “Well, look, let us jump first, and then you guys are welcome to have a jump afterwards”, and so often that they’d say, “Well, you guys look like you know what you’re doing, so be careful, and don’t hang around here for too long.”

I don’t imagine many of them took you up on that offer.

No, no, none of them did actually.

Is there anything that stands out in your career, as kind of a highlight, like maybe the craziest thing you’ve done?

Well, we’ve done quite a few crazy things, Ben. They all rank in for different reasons, but I think probably one of the scariest, most difficult jumps that I’ve done was I jumped off the Stock Exchange over the Chase Plaza. That was before the Auckland Sky Tower jump, and it was just really technical, and quite dangerous. The spaces were just so tight. Anyway, with all of these things, what I do before I do what I call a one-off jump, or an extreme jump, is we always test it with weights first, and try and simulate the jump the best we can, without a human being dropping. Then, if it’s going to be public, I’ll then do a couple of test jumps early in the morning, out of the public eye, just so I’m really comfortable with what’s going on, and the gear, and that the guys I’m working with are also really comfortable on the systems, and lowering me down, and the communication, everything, so it all goes to plan.

As mad as it all looks, it’s very well managed, in terms of risk. It’s something that we’ve … We don’t like pain, we like fun, and to ensure that, you’ve got to know what you’re actually doing, and understand where the risk areas are, mitigate them, you know?

I interviewed Dr. Keith Alexander a couple of weeks ago. He’s the inventor of the Springfree trampoline, and he said inventions are a little bit like a baby. When it’s first started, it’s pretty helpless, you have to be an advocate for it, throughout its life. It gets to a certain point where it’s a bit like a teenager, and starts to go off on its own, and form its own friendships. You need to be able to let it go, but it still wants to be in touch with you. Do you kind of feel like that is the story of AJ Hackett Bungy? It’s a worldwide phenomenon now. And your name is attached to it. Do you feel like you’ve had to let it go, on its own?

Well, it’s an interesting question, Ben. For me, I’ve been very much hands-on right from the beginning, so I’ve made a lifetime commitment to doing this for the rest of my life, in terms of that would be my main business and passion. What I’m endeavouring to do now, as the company gets bigger, is actually try to download so I have a lot less to do with the day-to-day. I’m finding that quite a big challenge, actually. We will get there. We’ve only, really, just started, even though we’ve been doing it for nearly 30 years, you know?

How big is the company now, in terms of revenue and locations, and how much bigger do you think it’ll get?

Well, we operate in about six different countries now, and we’re expanding. At the moment, we’re building in Sentosa Island, in Singapore. We will open next year, and we’ll be opening another site in China next year. Really, really big site there. Each site’s expanding and getting stronger, and the company will probably double in size over the next two to three years, so it’s on a big wave. You just have to be a little bit careful with that, because there’s only so many hours in the day, as well. That’s our big problem, is just keeping a bit of a reality check on your balance and quality of life, you know?

You’re 58, I think. Is that correct?

That’s correct.

You’re operating a global business, you’re travelling a hell of a lot. You’ve obviously had to make a few sacrifices along the way. What kind of sacrifices have you had to make, and can you find the right balance? I read a few years ago you had a serious car crash. Did that change your priorities a little bit?

Yeah, I think it did. When that accident happened, it was extremely close to everyone being dead, and everything over in an instant. It was definitely a wake-up call, even though I wasn’t the driver at fault, but that doesn’t matter. At the end of the day, we’re only here for a short time, and we have to make the most of every day. I had to change a few things in my life around that time, and I’m moving forward, and I like to make the most of every day. For me, a big part of that is focusing more on my immediate family, and spending a lot more time with my daughter, who’s now on a really good pathway for the next Winter Olympics, getting to New Zealand and the slope-style events. That’s really cool, to actually take some time out and support her and some of the other crew.

AJ Hackett jumping with daughter Margaux, 4, in Bali.

She likes jumping off things, as well?

Yeah. It sort of flows through the family, that gene. We’ve got an adventurous spirit that rears its happy little head on a regular basis.

You read stories about mountain climbers, or extreme athletes, or endurance athletes, and they tend to push themselves to their absolute limits. Often it’s not pretty, you read about death, and frostbite, and terrible injuries along the way, but there seems to be some joy in the completion, in doing something new. Is that the same for you, and maybe for the entrepreneurs that you’ve met on your travels?

Yeah, very much so. That’s the whole thing. There’s nothing wrong with failure. The issue is how you get back up, after you fall down. Same with most successful business people, entrepreneurs, athletes. They have a very common gene, which is persistence, and desire to continue to perform at the highest level. If you’re not falling over, you’re not trying hard enough. You have to make mistakes. That’s just what happens, because out of a mistake, you find many beautiful solutions. We don’t mind at all having problems because we know, well, we’ve just got to solve them, and once they’re solved, the door just gets opened a little bit wider, and there’s more opportunity. It’s really a discipline of knowing which mountain to pick, and when not to climb and when to climb it. I think it’s the same with business.

What stands out for you as some of those major mistakes, that in hindsight have been beneficial?

Gosh, we’ve had so many of them. I don’t know which ones you’d highlight. I think we’ve … One of the classic ones I suppose I’ve had is I introduced a product into our Cairns site, which was parabungy, jumping from parasails towed behind a boat. It looked very good, and I was convinced it would be a great product, and then when I actually experienced the jump, I realized, “Oh no, this actually doesn’t feel right”, then we didn’t realise in that part of the world, the winds would be too strong to actually sail at normal hours of the day, so you had really restricted operating hours, and it just about bankrupted our company there. It was just one of those things where sometimes your gut feel, especially when it comes to adventure, when you feel it, you go, “That’s either really, really good”, or, “No, I didn’t particularly enjoy that. I’m not so interested in it.” I think you’ve got to run with what you personally feel is good and then commit, as opposed to the other way around.

Another challenge you had along the way was with your co-founder, Henry van Asch, and as they say in Hollywood, you ‘consciously uncoupled’ [in 1997]. You took over the international business, but you joined up again in 2007. Was that hard at the time, and is it rewarding now, to be back in the same camp?

It was very difficult for both Henry and I, at that time, but we both needed to actually go out and do our own thing. We always respected each other, it was a different time of our lives, and we had different priorities. Now, we’ve grown up, we’ve matured more, and we’re great mates again. We work quite closely on a number of issues. It’s great. Henry and I have done so much together, and there’s so much water under our bridges, we’re mad not to be working close together and we have a lot of fun, also, which is hugely important for both of us, just to have that quality of life piece, where you can actually joke and you can be serious at the same time. A high level of trust and friendship is super important.

It seems like you obviously still love it, but do you also get a major thrill out of seeing that sense of achievement from all the people who face their fears and jump off a bridge? I know you’ve mentioned before that you never push anyone off, it’s all their own doing. That must be quite satisfying.

Yeah, well that’s the most satisfying thing of what we do, Ben, which is basically watching a customer go through the experience of jumping, or swinging, or sliding down a cable, or whatever the activity is, and once they finish that, and they’re back in their normal space, or their normal physical comfort zone, which is typically standing on the ground without a harness on, and you see the elation and the buzz that’s going through them, and they’re just feeling really good about themselves, you know that we’re doing a really good thing. We’ve always said, “Hey, look, the day our customers don’t enjoy what they’re doing is the day we’ll stop”, and 99.99 percent of our customers are very, very happy once it’s all over. It’s a different story at the beginning, when you have a lot of nervous people, but once they push themselves through their own personal barriers, they just feel a whole lot better about themselves, and it just puts a lovely little step into the next part of their lives.

There’s nothing wrong with failure. The issue is how you get back up, after you fall down. Same with most successful business people, entrepreneurs, athletes. They have a very common gene, which is persistence, and desire to continue to perform at the highest level. If you’re not falling over, you’re not trying hard enough.

Compared to selling the latest widget, or maybe broadband, you don’t usually get that kind of joy from your customers do you?

Well, as long as it works, I suppose.

There’s a fair bit of technology involved in bungy jumping that people may not really understand. Some of it initially came from the University of Auckland, and there are a range of other activities and adventure tourism businesses that you’ve started, like the Nevis Swing and others. Are you continually developing better materials, and technologies and processes, so that you and others can jump from higher places?

Well, I think a better way to describe it is, with bungy, we’re probably better monitoring it. We’ve got to stay on top of a system that we proved 30 years ago that it was consistent. There’s minor tweaks that can be made, and are made, but the big part of it is the human resource side of it, with bungy. We’ve had various steps of breakthrough over the years to improve safety, but predictability has always been pretty much the same, because that’s what we had to do from the beginning. It had to be predictable for us to survive, and the only unpredictable thing would be if you were stupid, like you forgot to measure the height of the bridge, or you didn’t connect yourself to the rubber band. That’s stupidity.

With new products that we are creating, and have created, then we’re going through the same process. We design it, look at it, pull in expert engineers from various fields and analyse it all, and then we go through the same testing regime where we drop, or swing, or push weights off structures until we’re completely satisfied that it’s all working, and then we test it on ourselves before we’re satisfied it can go out to the public.

There’s quite a process behind it, then there’s ongoing monitoring, constantly.

As you mentioned, it only takes one incident for that whole sector to be interrupted, and a little bit like airplane crashes I guess. No-one remembers the thousands and thousands of successful plane rides. They seem to remember the ones that go wrong. And there have been a few incidences over the years with bungy jumping that have been in the headlines. Has that been a perennial issue that you’ve had to deal with, about the safety concerns?

Yeah, well, we’ve always been very proactive about safety management. It’s been a key part of what we’ve done, and at 3 and a half million customers have now jumped with us, and crew, and we haven’t killed anybody, which is a very, very respectful safety record by however you measure that. However, there have been a lot of bungy deaths with other companies, and in all cases, it’s essentially human error related, and just being a little bit too complacent. For us, we’ve had some injuries, and that’s like anything a human being does. Most human beings have cut themselves, or have had a couple of stitches, or bruises, or broken a limb. That’s just normal human life. If you haven’t had a couple of bruises, then you’ve got to get out there and live a little bit. Live a little bit harder.

As well as the individual pleasure that you see from people who do jump off bridges and from swings, it must also be nice to look more broadly at what Queenstown has become, and what New Zealand has become, and think about the formative role that you played in that. Can you see your legacy continuing in the adventure tourism market here? Are there any companies or activities that have been developed that you’re jealous of?

I’m never jealous of anybody that does great things for people. I just encourage it. Henry and I have both been very supportive of people that are coming up with innovative, new ideas, and that just culminates in the Kiwi culture. There’s some amazing Kiwi’s out there, and they’ve taken a lot of cool things to the world. We’ll always be part of that. We’ll always support it. I’m stoked the way Queenstown’s expanded, in terms of its adventure tourism offer, and just a beautiful place to live and be. There’s great restaurants, accommodation offers, it’s just a cool place. It’s nice.

I fondly remember the jump nude and you jump free promotion. I wasn’t brave enough to do it, but it certainly made for entertaining viewing. Would you ever do a nude jump? Are you going to bring that promotion back?

No, I haven’t personally, but it’s been probably one of the longest running rumours, if you like. A few people definitely jumped nude, and for free, in the early days, but it’s something that doesn’t happen very often these days. That’s the odd special occasion, after hours, someone might leap off something without anything on and, hey, I’m pretty relaxed about that if that’s what turns you on.

Billy Connolly jumping sans clothes.

Billy Connolly jumping sans clothes.

The after hours bungy. I like it. AJ, what else have you got up your sleeve? You don’t seem like the type of guy who wants to slow down and quietly retire, whittling sticks on your porch. There are probably a few more records out there that need to be broken. What’s on the agenda?

Well, I’m more into just creating some more really beautiful spots around the world, working with some very interesting people and continuing to expand some of the stuff that we do. At the same time, just having a little bit more balance. Slow down on the work front, and just spend a little bit more time with family and personal stuff.

Often you see successful business people who do take that opportunity to move into more charitable pursuits. Is that something that’s on your horizon as well?

Yeah. I’m really interested in helping young people achieve their dreams where I can. Not only in a financial way, but a moral support level. I love watching people push themselves beyond where they thought they could go, and often there’s a lot of blocks in their way, and I think that’s something that we’ll end up doing a lot more of. At this stage, I’m very much focused really on my daughter and some of the people around her, as opposed to a wider picture. I just need more time, mate.

Well, you’ve already achieved plenty in the time you’ve had, AJ, and we appreciate you having a chat. Thank you very much. We look forward to seeing what you get up to next.

Cool, all right. You have a lovely day, and thank you very much for your time.

Billy Connolly jumping sans clothes.

Billy Connolly jumping sans clothes.