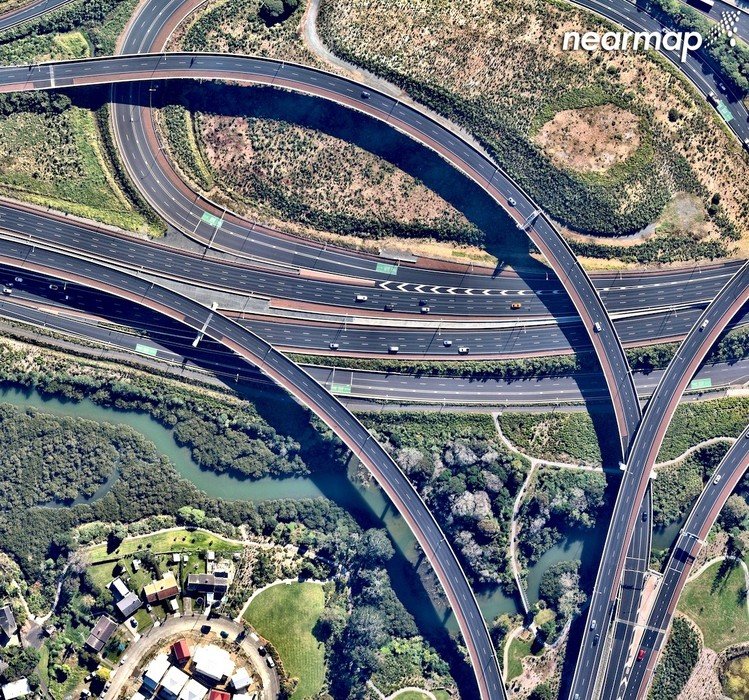

Birds eye views: Could the latest innovation in aerial photography nudge the construction sector into action?

Put simply, Nearmap uses aircrafts to fly over urbanised areas that take high resolution images of particular areas. It offers a subscription model, which supplies some of New Zealand’s largest enterprises and government entities, as well as sole traders.

Preston shares why its initial focus has been on urbanised areas, as opposed to monitoring deforestation, or agricultural erosion.

“We focus on urbanised areas, specifically we have collected content over the top 14 cities based on population size. Urbanised areas need to do the most planning, most infrastructure changes take place, and the most change in the built environment takes place. We tend to focus on urbanised areas first then expand from there.”

Its competitive edge compared to current aerial imagery services, Google Earth or LINZ, is its quality of images, regularity, and its accessibility, according to Preston, who puts it down to Nearmap designing, building, and iterating its own camera systems.

“We are always bringing new innovative ways to work to market, a pragmatic example is our latest tool to help customers plans and communicate projects to stakeholders, we supply from New Zealand’s largest enterprise through to sole traders, that breadth means we have a range of people who use Nearmap on a day to day basis,” he says.

The technology captures 72 percent of the New Zealand population. It is active in Auckland, Wellington, and Christchurch, as well as Palmerston North, Hamilton, Napier, New Plymouth, Rotorua, and Tauranga. Most of these areas continue to experience rapid urbanisation, which Nearmap captures on a regular basis. Thus, the public can see honest footage of urban erosion over a fixed time period. Here are some before and after visuals of developments in Papamoa, Manurewa, and Hamilton.

{% gallery ‘papamoa’ %}

{% gallery ‘manurewa’ %}

{% gallery ‘hamilton’ %}

Globally, a big design challenge is to aid the virus that is urban sprawl. According to The Guardian, our worlds cities are expected to triple in the next 40 years, chewing into our land and forestry. New Zealand is not exempt, as urban designers scramble to figure out how to build for more humans with better infrastructure, without eroding the planet. While Nearmap can’t control population numbers, or prescribe better design solutions, it can show how urban developments effect both natural and built-on environments over time, which can then be used for reference on future projects.

“When it comes to urban sprawl, Nearmap has a unique birds-eye-view approach. What we do is make those historical collections available to our customers. They can go back in time and see precisely how things can change, what may have been farmland, two or three years later could have tens of hundreds of houses on it with an entire community that has sprung up out of that farmland.”

It can also add value to New Zealand’s limp construction sector, a laggard in technology deployment, subsequently suffering from placid productivity levels that haven’t moved in 20 years.

Preston argues this is a global issue: “What is interesting you look at the construction sector globally, compared to healthcare or financial services, the construction sector has lagged in the uptake of technology compared to other industries. There are reports that show it could be as much as $1.6 Trillion USD that the construction sector is losing in productivity due to slow adoption in technology.”

He believes Nearmap can assist the construction sector to plan and survey projects, monitor developments, as well as offer accurate estimates and quotes on potential jobs within these areas.

“Construction companies that we have worked with, those kind of companies are looking to Nearmap to improve productivity to become more efficient, for example, eliminate site visits and inspections that could be done remotely from their desktop. Globally the sector is lagging, but certainly there is a demand from NZ businesses in this sector to be more efficient or effective.”

It’s timely, as Kiwibuild planners and developers languish in the throes of atonement, while other smaller scale projects take hold in new suburbs around Auckland, such as Hobsonville Point, Papakura, and Coatesville.

Preston adds, “Flatbush in Auckland is also an interesting example of development. On one side of the road the houses were built decades ago, on the other side of the road there is a group of houses that have been created over the last few years. These tend to be much larger, the blocks are much smaller, and the proportion of the land that has been taken up by the building in substantially higher. It’s a fantastic example of how the urban planning and urban development community has changed over time.”

Asked if there were similarities between developments in New Zealand and towns or cities offshore, Preston says, “Based on the size of the city, the North Link project in Perth shares many similarities to Auckland, it is a city that is rapidly growing and needs to continue to evolve its infrastructure to allow people to get around and maintain the high quality of life the city is on for”.