The breast solution: How myReflection is taking 3D printing to women with mastectomies

When Fay Corbett went through two years of treatment for breast cancer and had a mastectomy on her left breast, like any partner would, Tim Carr wanted to do anything he could to make things better.

Although the couple kept an “awesomely dark” sense of humour throughout everything, Carr noticed how Fay wasn’t comfortable with the prosthesis she received, how people would look at her funny if it moved around, or was sitting high, and how it could slip out of her bra or gape from her chest.

“She spent a lot time dealing with it,” Carr says. “The summary of that would be that it’s better than nothing, but only just.”

Traditional prostheses cost between $450 to $550 per unit, and a mastectomy bra is another $150, taking you to the limit of the Government’s breast prosthesis subsidy, which is $613 per side every four years. Carr says although it’s great the Government has the grant, one prosthesis doesn’t last four years and the material of the prostheses just isn’t up to standard.

“We have really heavy silicon lumps that don’t sit as part of you, they’re really just the best you can do with something really horrible,” he says.

“You think of a nice clean flat chest afterwards with the breast gone but it’s really not, often there’s large amounts of skin and big scars that are raised above the chest wall and you’re squishing something into that all day that’s heavy and hard, it’s really difficult.”

Carr thought there had to be a way to improve the experience for Fay and all the other women dealing with generic prostheses, and with his knowledge of 3D printing, having founded 3D printer supplier company MindKits, and his expert employee Jason Barnett, the mission for customised prostheses began.

Carr says the goal behind myReflection is to reconcile what a woman sees in the mirror with what’s in their mind’s eye by creating a prosthesis that feels and looks like their breast did before undergoing a mastectomy.

Top: Co-founders Tim Carr, Fay Corbett and 3D printing expert Jason Barnett. Bottom: the 3D printing station.

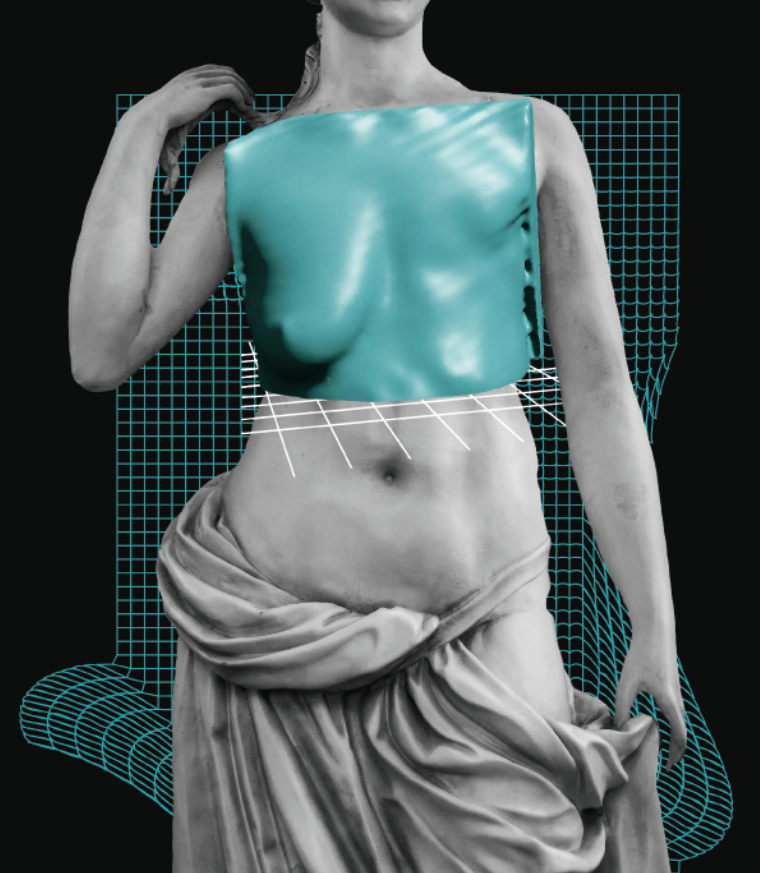

The starting point: chopping up ancient Greek statues, taking off their breasts, 3D printing them and giving them to Fay to put in her bra to try out.

Carr says immediately the group saw there was something there, with the models looking like normal breasts rather than the generic prostheses, which are hard silicon lumps that resemble mousepads. From there, it was one year of solid work figuring out how to get to where they wanted to be and questioning every decision made and process chosen.

“I was wondering whether we were crazy and if this had become an obsession and we were working on something that no one else was going to see the value in,” Carr says.

“Everyday Jase and I were talking, every day we were questioning is this the best way to do this, can we improve this, can we change this, so for us, it became the new normal.”

You think of a nice clean flat chest afterwards with the breast gone but it’s really not, often there’s large amounts of skin and big scars that are raised above the chest wall and you’re squishing something into that all day that’s heavy and hard, it’s really difficult.

The pair came up with the first prototype and gave it to Fay to try, even though it was “the most hacked up thing you’d seen”. A week later, Carr asked for it back so she could try the next prototype and she looked at him with horror.

“She said ‘No, you can’t have it’ and I was like ‘Why?’ and she said ‘Because it’s me’,” Carr says. “She’d formed such an emotional bond with it that it looked like her, it felt right against her, it felt warm like she was, so she didn’t want to give it up – it was her.”

With that validation, Carr and Barnett delved further down the entrepreneurial rabbit hole, putting in thousands of hours, giving up a number of times, and shedding tears hours before presenting to 60 breast care nurses.

The tears came on because a perfect demonstration prosthesis collapsed hours before it was due to go on show, a learning curb for how the various materials they were using interacted with unintended effects.

What the pair are doing hasn’t been done before, so they are pathing the way with the process and materials and are learning as they go, Carr says. The concept spent a year in R&D which was fast-tracked last September when Weta Workshop opened their doors to the pair and shared their knowledge on material science.

Even with that, the properties of customisation and handcrafted goods are the antithesis to mass production, things they are trying to wed together for myReflection’s future, he says.

The method used to create myReflection prostheses involves taking between 170 and 200 photos of a client’s chest and torso to create a 3D mesh using photogrammetry, which is used to create a model of the client’s chest wall. They then mirror the existing breast or can use one from their breast library to create the main body of the prosthesis.

From there, the team use a 3D printer to make the mould and use their unique manufacturing process to create the perfect prosthesis from the original scan. The material weighs between a quarter and an eighth of traditional prostheses and is an ISO certified skin safe silicon on the outside, but the secret core is where the magic lies, Carr says.

The process and materials they’ve come up with enables the mould to be extremely light and consistently compressible, feeling like normal fat or tissue.

“The first thing that we hear is, ‘Oh my god, it’s so light,’ and the next thing is it squishes properly, and the next is why is it so bumpy on the back,” Carr says.

“That allows me to tell them it’s bumpy on the back because we scan your chest wall, so instead of it being like a water balloon it will sit perfectly against your chest wall and all the undulations and peaks and troughs that become incredibly tender, especially with the sensitive scar tissue.”

Since myReflection launched at the start of February, Carr says they’re seeing women that haven’t used a prosthesis in 15 or 25 years suddenly coming out of the woodwork who are really interested to see what the new product is like.

Barnett, who started studying 3D printing in 2009 in one of the first intakes at AUT, says he predicted it to be one of the most transformative industries with the greatest impact.

“Where I expected it to be in ten years is essentially where it is. It’s starting to replace many traditional methods of manufacturing and disrupt traditional manufacturing structures.”

The work he has been doing with Carr has been groundbreaking in the 3D printing field and admittedly has been a huge uphill battle, he says. That battle has had three parts: not compromising on the end model and making a subpar product, customising everything at scale, and keeping the cost down.

“We want to make sure the cost of it doesn’t generate an elite product that only a small portion of the community can afford, you want something that is democratised with access and is available to everybody. So trying to balance those three things was really our foundational understanding.”

The goal behind myReflection is to reconcile what a woman sees in the mirror with what’s in their mind’s eye by creating a prosthesis that feels and looks like their breast did before undergoing a mastectomy.

Women can subscribe to myReflection on a four-yearly basis in conjunction with the Government breast prosthesis subsidy. For the $613 that is allocated to each mastectomy patient every four years, they can get the consultation, scanning, modelling and four prostheses.

Throughout the creation of the business model the pair have kept scaling in mind, which has taken them down a lot of different paths of production and to a lot of dead ends.

“We did prototype to final version about four completely different ways, we’d come with an idea refine it, get it close to it being the final version and no, out the window and we have to start all over again,” Barnett says.

The level of patience and persistence required to persevere through that was extremely high, and the pair kept their sights on the end goal with much reassuring and the occasional hug to get through it all.

Barnett says after being crushed more than once during the year of development, the final product and launch at the start of February has left him ecstatic.

“Not just because we’ve successfully made something, but when we had our launch event speaking directly with all of the women who are affected by this and have been for decades and continue to be daily, the community was essentially screaming for something else.

“Every single person said nobody likes what exists now, the only reason it’s there is that we have no other options, and that was the validation. They’re basically lining up saying when can we have this, when can we try this, we want this.”

He says unlike a normal product where you have to implement a marketing scheme to convince people to buy it, myReflection prostheses is something people immediately see the value in and recognise as life changing.

Barnett says a huge part of his and Carr’s achievements are on the manufacturing side with the process they’ve developed.

“There is nothing that’s been done like this anywhere around the world, these are next generation approaches, new business models to traditional mass manufacturing, and it’s quite revolutionary, not just the product but what’s behind the product.”

Within the next ten years, Barnett expects the end of the need for organ donation, saying the vast majority of organs that someone would require could be printed on demand. He says skin cells could be harvested and reverse engineered into stem cells that could be used as a printing medium to produce a liver, for example, that would have no potential for rejection being made from the patient’s cells.

“You don’t have the waiting list or anything like that, we’re talking about having the ability to produce it within 24 hours of taking the sample.” He says that same approach could be applied to skin, bone, muscle tissue and cartilage.

Auckland Hospital is already using the MindKit’s Ultimaker 3D printers for surgical pre-planning, printing model bones from CT scans and working out how to undertake surgery prior to the surgery itself. This means doctors save a lot of time during surgery, knowing exactly what they want to do when they open patient up.

Going forward, Barnett says 3D printing will continue to have a huge impact on the medical field and how designers, creatives and medical professionals approach challenges. He and Carr have ideas of taking what they do with breast prostheses and looking at other medical applications, like reinventing socket interfaces for people with prosthetic limbs, and other formed based modifications for people in the transgender community and all types of things, he says.

But in the immediate future, the pair are focused on growing myReflection and making it available to as many women as they can.

After partnering with Bendon, they cover all of New Zealand with agents in remote locations using their scanning rigs and sending the data back to HQ to be processed and crafted. The next step will be heading to our neighbours across the ditch, and then onwards.

Already, they’ve had doctors and surgeons from as far as Canada knocking on their door.