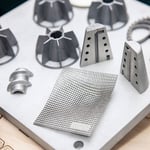

Ever wondered what the sounds of your life would look like 3D printed in white nylon? Or what they do in a megatronics lab? Or what 200 game developers would talk about if they were all in a room together? Or how you might incorporate conductive fibres into a ‘smart’ shirt so it becomes ‘wearable technology’? Or why all those white dots on your face are necessary to turn you into an avatar? Or how you print an industrial widget from stainless steel powder using selective laser melting (spoiler alert: it isn’t anything like printing a plastic toy from one of those loud desktop 3D printers).

OK, so you maybe didn’t ever ask these questions? But if you did, chances are Colab could give you the answer.

Set up in 2008 as the inter-disciplinary unit for AUT’s newly-created Design and Creative Technologies faculty, Colab’s mission was to get students and researchers from five disparate academic disciplines – art and design, communication, computer and mathematical sciences, creative technologies, and engineering – talking and working together to encourage innovation in new areas, in particular creative applications of newly-developing technologies.

Others see chaos. We see experimentation and discovery… Around 30% of graduates from the programme go on to found their own business.

Artists working with programmers on interactive art for big screens, for example, or engineers collaborating with fashion designers on wearable tech.

The original founders still head up Colab – architect Charles Walker, and Frances Joseph, who was an artist working in sculpture, installation, puppetry and animatronics.

Joseph says she has always been interested in how creativity and science come together.

“My father was an electronic engineer and my uncle was a professor of English and a poet. So I always had two dimensions to myself: technology and artistry.”

Still, creating an interdisciplinary organisation within a university structure hasn’t been easy.

“What we were doing was quite radical six years ago. People were talking about collaboration between disciplines quite a lot, but it’s a hard thing to do, particularly in universities, which tend to be focused on disciplinary expertise – deep and narrow – with funding associated with students in different areas.”

Has it been worth it?

Definitely, Joseph says. Collaboration is crucial.

To take just one example, there are no university courses where people study advanced engineering and advanced textile design together, she says, so if you want to develop wearable technologies or e-textiles, you have to have some way of bringing these different areas and experts together.

“The wearable technologies group includes textile designers, PhD students, electronic and mechanical engineers, nanotechnologists, computer programmers, physiotherapists and health scientists, as well as industry partners.

“The researchers come from different disciplines with different cultures. They understand things differently and speak different languages.”

In general New Zealand organisations don’t do collaboration well, Joseph says, though we are improving. “Maybe kids do it better, but our systems – university, business, government – aren’t geared for collaboration.”

Labs network

The word “Colab” conjures up (in this mind at least) a Silicon Valley-like white space, full of muted groups of students, perhaps in lab coats.

The real thing isn’t like that at all.

Without its own building (though it may get a home in 2018 as part of AUT’s rebuilding programme), Colab has snuck, magpie-like, into other people’s spaces.

3D printing is at the bottom of the science and engineering block; textile and design is tucked in the basement of an unlikely building near the top of the campus; PIGsty is currently a virtual group, managed through Colab, and is waiting for confirmation of its own physical lab space.

Then, several floors above PIGsty is the megatronics workshop – grandad’s shed taken over by the teenagers.

Handtools and drills sit alongside 3D printers and old oscillators salvaged for parts – the workshop is a glorious treasure trove, open once a week for anyone who wants to work on their own projects, exchange ideas, and collaborate.

Project-based learning

There’s almost no stand-at-the-front-of the-classroom-style teaching at Colab, Walker says. Instead, the curriculum is project-based – with the projects mostly devised by students themselves. Some visitors used to the old, traditional way of academic teaching can be a bit horrified, Walker says. But students (and mostly their parents) “get it”.

And if success is measured in terms of how much innovation you foster, Colab is winning. Around 30% of graduates from the programme go on to found their own business.

“Others see chaos,” Walker says. “We see experimentation and discovery.”

Six years after the Tertiary Education Commission handed over its first $1.4 million of funding, Colab now has 200 students, 17 staff, and four labs – 3D printing, textile and design, motion capture and PIGsty (play interactivity and games). There’s a data visualisation lab coming on stream in 2016 where researchers will be looking at new applications in areas like virtual realities, tangible interaction and the design of immersive spaces. And Colab staff also run a series of regular meet-ups and hackathons – from game development to digital art.

Collaboration culture

At any one time there are dozens of projects going on in Colab, says Walker. Some involve undergraduate student teams, others post-graduate researchers from various disciplines, and the teams often work with academic staff and people from industry, business and the creative sector.

“There is a lot of emphasis on teamwork with the students – students develop and disband teams on a project-by-project basis. That’s how the world works, but it’s one of those overlooked skills in universities – how to fit into teams, work with people and be constructive.”

Widening partnerships

At the moment, Colab is working with about 10 business and community partners, including Spark (formerly Telecom), Walker says, with an emphasis on new technologies and digital futures.

“Everyone talks about disruption, so if the world is changing because of new technology, what are the new products, services, business models, careers and organizational structures that are going to be successful. That’s what we are interested in.

“With external partners, we like to sit down and run ideation sessions; work out what the questions are, and agree a path forward, rather than start with them telling us their problem.

“For example, Spark knows it can’t be a telco, it has to be a digital service provider, so what is its future in the new digital economy?”

And Colab is also growing in other ways. Last year it took 50 first year undergraduate students; this year the intake was increased to 70. The school typically gets 350-400 applications. Now the focus is to boost post-graduate numbers from 35 to 60 by 2018.

“We tend to attract people who are at the edges of their own discipline,” Walker says. “They might be an engineer that became interested in mechatronics, or an artist who wants to get involved in technology, or a programmer who wants to do something creative, like film or motion capture.”

The biggest challenge Colab faces, Joseph says, is keeping ahead of the game, when the game is digital futures. But when it works, it’s worth it.

“One of the best moments for me was finally getting electrical engineers working with textile designers in the field of wearable tech and e-textiles. It was a five-year process to get this happening because fashion and engineering are traditionally seen as opposites… predominently female students versus almost exclusively male, ‘frivolous’ versus serious, creative and expressive versus scientific and mathematical.” ?