Is influencer marketing over-saturated? Scapegrace and Motion Sickness team up to teach you how to influence for launch of new RTD range

As we close out the end of a decade, it’s safe to say the 2010s have been a wild ride for influencer marketing. There’s been incidents where reality TV stars have accidentally copy pasted brand instructions into their promotional posts (Scott Disick), influencers doing damage control trying to distance themselves from festivals that are not dissimilar to a dumpster fire (Fyre Festival) and panicking in the community when the tech giants have culled fake followers. But for all its flaws, influence marketing remains one of the most effective ways for brands to reach consumers. Scapegrace gin recently launched a tongue-in-cheek campaign with New Zealand influencers to take the mickey out of the profession, while also promoting its new RTD range. Here, Motion Sickness and Scapegrace take us inside their thinking and have a chat about the state of influencer marketing.

Influence has always been the key to marketing a product or business effectively, from finding it, to amassing it, then using it effectively to achieve objectives. Long before social media existed, Coca Cola recruited the Santa Claus character to very effectively sell its products.

Closer to home, perhaps Vince Martin could be granted influencer status for his infamous ballad in the Beaurepaires Christmas ad (how many tyre sales were made? Who knows, but it sure did warm the cockles of my lifeless heart). Elsewhere, who could forget the nameless hero in the beige stubbies from the World Famous in New Zealand L&P campaign.

However, the 2010 have ushered in a new era, where most people’s eyeballs now spend an unhealthy amount of time scrolling social media. Those with a large following on these platforms have been able to capture advertising spend through wielding products or services to the masses, but has influencer marketing gone too far?

For one, there’s the concern that in some cases, the influence is not actually authentic – it’s inflated numbers that people have bought through ‘follow farms’. CBNC reports that fake followers will cost brands US$1.3 billion in influencer campaigns in this year alone.

As well as this, media agency UM found that just eight percent of people believe the bulk of what they see on social media is true – and they believe just four percent of the information that comes from influencers. After all, if one fitness influencer is seen flouting five different brands of protein, the consumer starts to question whether they actually believe in the messaging, or if it’s all to make a quick buck.

Head of strategy at Motion Sickness Hilary Ngan Kee says authenticity isn’t a big concern with the New Zealand influencer market. If anything, the main concern is New Zealand’s small size.

“The pond isn’t that big, therefore there aren’t a whole heap of fish out there to work with. I think this if anything makes New Zealand influencers more genuine, as I think they put a bit more effort in to ensure any collaborations they’re doing are authentic – and half their followers are probably a friend of a friend, so they can’t really be too fake without being called out,” Ngan Kee says.

“The other advantage of this is that influencers here arguably have a closer and more influential relationship with their followers than in larger countries. I mean, the chance you’ll bump into your favourite person of influence on Ponsonby Road on a Friday night is pretty high.”

So, it seems there are both pros and cons to our country’s uniquely small social media scene. The two degrees of separation New Zealand is famous for creates a more authentic connection to small yet highly engaged audiences, but it means there’s also a large number of brands vying for the attention of influencers’ social media followings.

Motion Sickness creative director Sam Stuchbury says the market is fairly saturated in terms of the amount of sponsored posts the bigger influencers are doing, so it’s important to try have originality and a creative approach to influencer campaigns.

“In our opinion, influencer marketing is no longer a unique or innovative idea on its own – it’s mainstream,” Stuchbury says. “Because the space is getting more saturated I think we’re going to see a whole lot of people putting more time and energy into the creative process, and also integrating their influencer activity more with their other advertising activity.”

One example of taking an out-the-box approach to influencer marketing is the recent campaign Motion Sickness did for Scapegrace. To launch Scapegrace’s brand-new RTD drinks into the market, it teamed up with Motion Sickness and did a tongue-in-cheek campaign with local influencers.

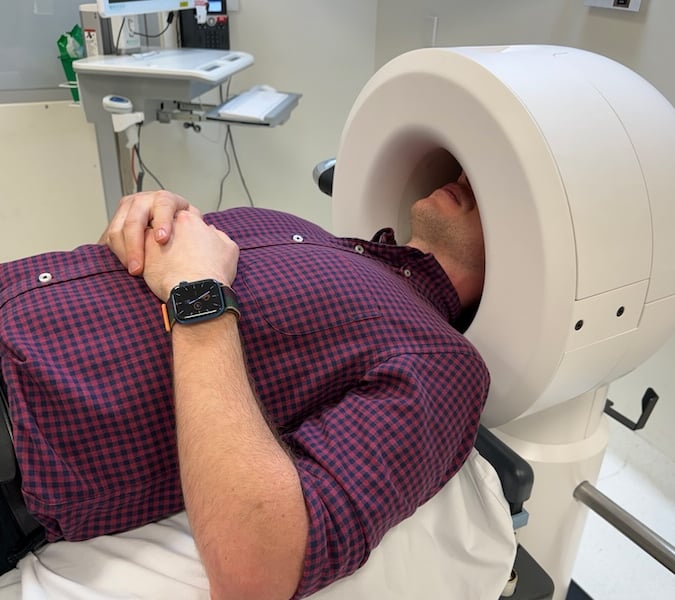

Scapegrace sent out a fun pack that included a case of the RTDs, a large poster of a beautiful beach backdrop, and instructions on how to pose right down to the centimetre so that it looked like the drink was being consumed at the beach.

Scapegrace founder Mark Neal says influencers haven’t been a major marketing driver for the company in the past, so with the RTD launch it was time to test the waters.

“Most consumers now expect much of the same when influencers peddle a beverage (hand holding a bevvy in front of their phone), so we took a meta approach and flipped that on its head – might as well leverage the same repetitive content to our advantage, right?” Neal says.

“It isn’t at the expense of influencers, but it’s a satirical dig at the realm of Influencer endorsement – consumers and influencers alike are totally aware of how predictable their content can be.”

Stuchbury says doing things differently is a big part of the Scapegrace brand’s DNA, seeing as the gin brand made an unexpected entrance into the RTD category. Its tongue-in-cheek approach was brought through to its influencer activity.

“The RTD campaign itself was a bit of a meta satirical commentary on influencer marketing, using an ‘influencer kit’ to ask them to take the ‘perfect’ sponsored post (the classic product in hand shot that seems all to common these days). We provided the people of influence with a classic summer background so they could do their work without even having to leave the house. Do influencers have it to easy? In this case they really did,” he says.

Alongside the social media influencer campaign, creative campaigns for digital and outdoor were rolled out too, linking a series of quirky, bizarre problem solving video scenarios to the recurring mantra ‘You’re Welcome’. One features a man gyrating and also trying out a hula hoop.

“Each random, sporadic concept behind the videos were purely to have cut through in a busy space – the opening predicament was the bizarre prompt that we wanted people to stop scrolling for, and then the solution would drive home the product and campaign mantra,” Scapegrace’s Neal says.

In terms of statistics, the campaign reached over half a million New Zealanders on social in the first week, with more than 200,000 post engagements.

It’s clear that when executed right, influencer marketing is here to stay. In this disinformation era where the digital world is getting increasingly cluttered – and advertising is entangled in every corner of the internet – influencers can cut through the noise and become a trusted voice on an issue, a content creator, or an expert in their field.

Or at the very least, like with the Scapegrace RTD campaign, they can be self-aware enough to acknowledge the pitfalls of their profession – and are ready to have a laugh at their themselves over the ridiculousness of it all.

Check out the new range at Scapegracegin.com.