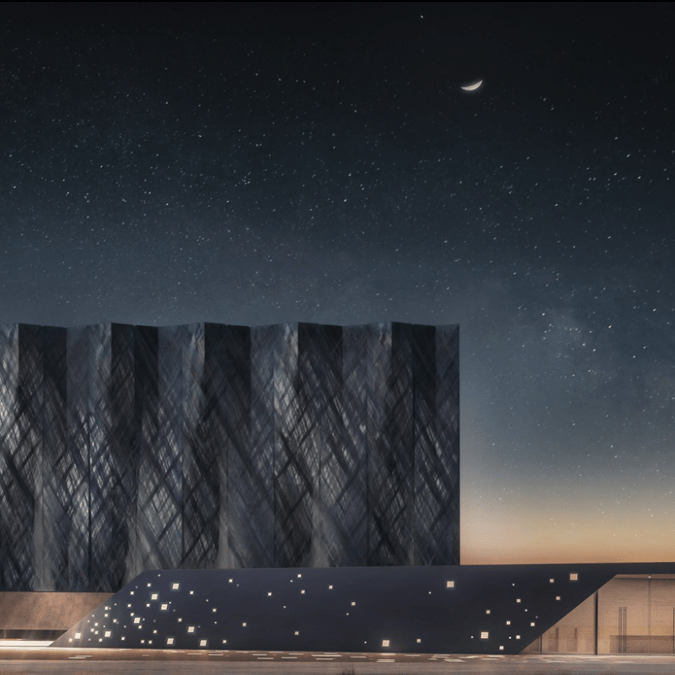

How Auckland International Airport’s Departure Experience redesign draws from the past, while adapting to the future

Some people believe to look into the future of a city, you need to look at its airport.

Across the world, airports have turned from ‘non-places’ – indifferent factories focused on processing passengers – into cities themselves. They have become cultural vehicles, emblems of wider urban landscapes, and in some cases visions of technological change.

The development of airports has also reshaped the role of the architect. In today’s age, urban designers are tasked with building a meeting place of mobility, experience, culture, business, technological change, and the environment.

Although many airports across the world still have no sense of place, similar to malls and supermarkets, others have become symbols of a regional or national typography.

CityLab recently reviewed the airport in Indianapolis, for example, which has turned its airport into an authentic, pleasant public space for people to linger and spend time in – more like a museum or an art gallery.

As airports expand into city plazas (which in some cases feature yoga studios, dedicated green spaces and even butterfly gardens) travellers have naturally altered their patterns of behaviour. People now spend more time in airports, partly because of tightened security measures, but also because architects and planners have turned them into comfortable commercial city spaces.

Perhaps, in coming time, people will arrive early to airports, enjoy the retail offerings, interactive technologies, public art, or food offerings, rather than scuttle through the thoroughfare.

For Auckland Airport, it has fought to balance expanding its infrastructure with the customer experience as passenger growth has surged ahead in recent years. But the idea that airports are destinations in their own right is one the Auckland Airport hopes to deliver with its Departure Experience redesign – a process that has been 10 years in the making.

To do so, it has examined the passenger journey. Gensler’s MacKenzie explains, for example, the tension between the airport needing to function for the efficient traveller who wants to get straight through the terminal, but also for the enjoyment seeker who is inclined to engage in something interesting and different.

Moyes reiterates the need to meet the demands of different types of travellers: “As a traveller, there are moments when you are extremely happy and engaged with the process and there are moments that people are typically quite nervous.

“The queue is too long to get through security or handing over the passport to get your face scanned. Depending on the type of traveller, those can be very stressful or very easy processes. So, one of the key opportunities was to completely reshape that experience for Auckland Airport, so that passenger journey was an exemplar at an international level, not just in New Zealand, but on a global stage.”

If you build it, they will come

One of the practical considerations the airport is building for is the rising number of international travellers. The Auckland Airport predicts 10 million passengers will pass through the international terminal each year.

To meet the demands of extra people, it has upgraded the international departure area to be comprised into three districts: a reconfigured landside farewell area, a new emigration hall, and a new retail hub and passenger lounge. It will double the span of the dwell area, increasing the duty-free area from 6,000 to 12,000 square metres.

Additionally, the project deals with what Moyes calls, “the legacy projects that have been happening over the past three decades”.

These legacy projects include a number of transmutations to the original design of the airport from 1977. The project delivers 35,000 square metres of combined new and renovated building floorplates to either replace or reshape the existing fabric of the Airport.

A key focus was to allow flexibility for the airport to expand further in the future – to account for accelerated population growth and technological change.

Rather than simply demolish and replace old legacy niggles, both Jasmax and Gensler have repurposed qualities of the original airport to combine with its modern features. For example, a heavy-duty laminated timber flooring system was used to raise the floor level by 1700mm, plus two major plant rooms on levels two and three are new features of the terminal development.

It’s required some patchwork, according to Moyes, who outlines old design remnants that have been hidden in the airport, including areas in the existing terminal that had slabs at differing levels. He says the team looked to simplify and standardise the terminal.

Opening the cultural gateway

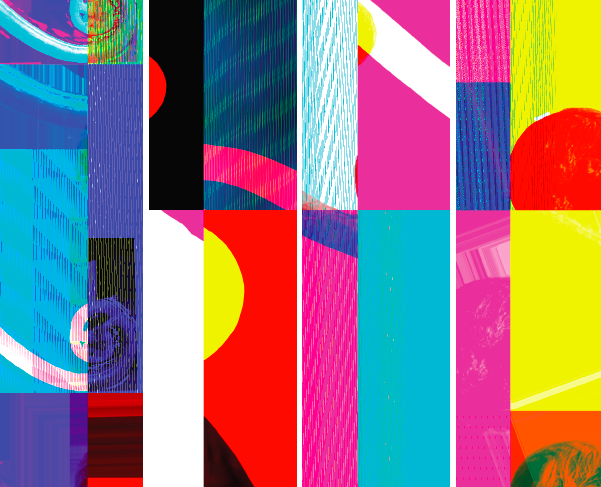

Another key feature is the renewed public artworks displayed in the departure lounge of the international terminal. The artist committed to the revival is Dr. Johnson Witehira, whose artworks will provide voice to Aotearoa’s multi-cultural identity to the millions of visitors who enter our country, but also to local people who return home.

MacKenzie says, “The overarching design narrative, ‘a journey through New Zealand from the sea to the sky’, allows us to look at the various spaces along the route and brings them back to a moment in that journey. It also allows us to connect with local people, local landscapes, and local design ideas like Johnson who has taken stories shared by local iwi and been able to weave those into the architecture.”

Witehira is a designer of Tamahaki (Ngati Hinekura), Nga Puhi (Ngai-ta-te-auru), Ngati Haua and New Zealand European descent. But his artwork also carries the voice of three different mana whenua groups, Te kitai-Waiohua, Te Kawerau and Te Ahiwaru, who were closely involved in the project. He has reached acclaim for his large-scale installations of public art, projecting Maori voice in public places across the globe, including in Times Square, New York, Courtenay Place, Wellington and also on the noisey walls of Auckland’s Southern motorway. Yet the airport presents its own challenge, to provide a gateway into our cultural heritage.

He says, “Artistically, I went through a similar process as I do on all of my other projects, where I didn’t necessarily look at other precedents of previous airports.

“One reason I was interested in the project was the integrated approach. I am an artist and a designer, and those mean very different things, but for the airport, as a designer from a pragmatic place, it wasn’t about making a stand-alone artworks or carvings, it was about creating things where our cultures were woven into the fabric of the architectural design in a way that for people who walk past them, they can look at them and see pieces representative of our cultural heritage embedded into the walls.”

Conceptualising Aotearoa’s identity caused conflicting opinions about what our identity actually looks like through the eyes of different bodies involved in the rebuild, as well as the general public.

“There is a lot of pastoral care in the process, trying to figure out the best way to navigate the process of both the iwi and the stakeholders,” Witehira says. “The biggest challenge for me was to put in elements that spoke to Maori, non-Maori, mana whenua specifically, through the design. It’s about finding the stories iwi are sharing, finding how those stories relate to the spaces and the nomadic journey, and then start designing from there.”

Each piece connects to the wider theme: a journey from sea to sky. It weaves the arrivals of Maori and Pakeha represented through a series of artworks, both in overt and subtle form. Witehira explains this nomadic journey for the traveller: “starting with departures on the shore going across the land, up a maunga and into your waka rererangi into the sky”.

“They will see little carved details added onto the walls, onto the chairs. They’ll see elements stencilled onto concrete pillars and again it was about integrating some of the iwi stories, but also stories about being New Zealander Maori and Pakeha into this building.”

A key focus agreed by all parties was to shift from tokenistic forms of New Zealands cultural representation – such as the commonly possessed jandals and buzzy bees – to a sophisticated response pulled from Maori settlement in New Zealand. It’s not the first time the airport has drawn on our bicultural heritage. In 1977, the airport commissioned Ralph Hotere to provide a symbol of our country’s landscapes and heritage. The result saw a multi-panelled 30 metre mural named The Flight Of The Godwits (referencing the long migrations by native kuakua) which adorned the walls of the International Customs hall. It was hailed as one of “the most ambitious pieces of public art” of our time.

However, during an airport rebuild in 1996, the jewel was quietly removed alongside fellow artworks by Pat Hanly and Robert Ellis – an act described by New Zealand art curator and commentator Hamish Keith as a ‘breathtaking piece of public carelessness’.

But while the airport has previously adopted stand-alone artworks to represent our bicultural heritage, the redesign is the first time these message have been threaded throughout the entire discourse of the departure lounge.

“They are not stand-alone Ralph Hotere pieces along the way which some people can engage with or not, the design speaks of our bicultural heritage,” Witehira says.

“I think a big part of the message is of Kotahitanga, of being together. All of the design elements that I have tried to create have bicultural elements, one example is the carving in the very first portals. Those are in a place of the journey that talks about arrival and that arrival occurred by greeting the sea, that are that are based on Kotahitanga and naturalistic elements.”

The balance of modern architectural applications and subtle artworks has resulted in an international departure lounge built for all types of travellers. The artworks of Johnson Witehira provides a series of touchpoints that offers a passport to our Maori heritage, but they also work as way finding to those who prefer to move through the terminal efficiently.

It presents a wider declaration for Auckland to shift from tokenistic representations of Maori culture – a ‘chuck a koru on it to tick that box’ mentality – to a mature and subtler response that informs visitors of our rich and vital indigenous history.