White Mirror is a series that considers the positive human impact that can be achieved with the help of machines. In this second episode, you follow the life of Stefan Rochfort, the tech-for-good advocate who’s working to democratise the disability rights movement. Read how the overcoming of his mental illness gave him the emotional toolbox to build an empathy-inducing VR experience. And how this simulator creates awareness not only for profound disabilities, but also the perceived barriers we mistake for our weaknesses.

Leave behind all of your expectations and preconceived ideas.

If while you’re reading this, you begin to judge the words or feelings that arise, try to suspend them… if only for a minute. You’re about to glimpse an alternate reality; one that’s available to you right now.

Welcome to White Mirror.

Part One: Locked in

Imagine you’re unable to communicate with the world around you. Trapped inside your body, with all the thoughts, intentions, hopes and frustrations you’d usually experience in a given day. Try to imagine what it would be like not being able to move your limbs or express emotion.

This is the nightmare that South African, Martin Pistorius, spent 13 long years locked in. From age 12 to 25 he was in a vegetative state, diagnosed at best with the cognitive capacity of a 3-month old baby. His caregivers treated him as such – wheeling him in front of the television to watch Barney. Behaving in ways people do when they think no one is watching. In some instances, even committing crimes of abuse. It wasn’t until a new support worker had a hunch he was trying to communicate with his eyes, that Martin was retested and then given an assistive communication device. He’s since had a child, completed a degree and written a book.

“I cannot even express to you how much I hated Barney.” – Pistorius

Let’s face it – it’s a rather complex task imagining yourself locked inside your body for 13 years, let alone any of the other horrendous indignities that might entail. This is the ‘why’ for digital media creative, Stefan Rochfort, and his wife, Dr Sarv Taherian. Their work involves software, psychology and human narrative, to back fill our lack of first hand experience with disabilities like Martin’s, and the diversity of needs across the disability community.

A self-described ‘fashioner of new hats to wear in a capacity that’s useful for others’, Stefan is designing and building experiences that grow deep empathy. The first of these – an immersive VR simulation called “Talking Mimes” – short for Talking Mimes Must Die, an ode to Martin’s loathe for Barney.

Used internationally by students, professionals and the general public at TEDx Auckland, the University of Canterbury, disability support organisations, hospitals and assistive technology companies.

Talking Mimes is not only an interesting application of the often over-hyped virtual reality technology, but also at the cutting edge of a new wave within the diversity and inclusion movement. It’s important, because even in these comparatively woke times, disability is often the last item on diversity checklists, if it’s there at all. Arguably even more wonderful, it’s also had some beautiful impact for the families of those with profound physical disabilities.

That’s because Talking Mimes is a 12-minute simulation that makes you feel the intense frustration, helplessness and disempowerment that you are trapped with when you have a profound physical disability. Revealing how the problem isn’t with the individual you become, but the way society treats you in the 12 minutes behind the headset, and them every moment of their lives.

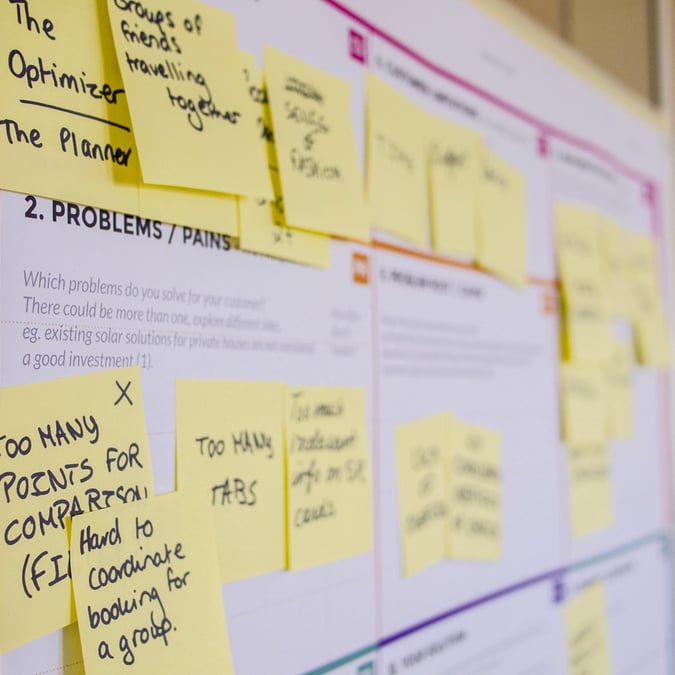

Co-designed with people who have the lived experience of profound disability and their families, drawing from personal interviews, case studies, biographical and scientific literature, the experience sets out to challenge both traditional low tech and modern VR/XR simulations, which can often be problematic and downright insulting to those with disabilities.

As Stefan says, Talking Mimes is trying “to start a practical conversation around safety and respect. To actively reject the soft bigotry of low expectations. To peel back the layers of alienation and teach us how to be less accidentally condescending arseholes, and more on-purpose good humans.”

And we certainly need more good humans in this world.

Part Two: Having a certain kind of mind

When he was young, Stefan suffered severe depression punctuated by multiple suicide attempts. It was made worse by the two-fold guilt he felt for both putting his parents through the secondary trauma of having a suicidal child, and for the fact he had grown up in relative privilege with a loving, supportive family.

The mental toolkit he developed to survive his own mind made him more resilient in the long run. And his experience with mental illness has given him insights and sensitivities he wouldn’t otherwise have. This ‘strength from weakness’ (or perceived weakness) has been a common theme for him, and a motif he can’t stress enough runs deep through the disability community.

With one foot in the film industry for a while, Stefan won a couple of things, got paid actual proper money to write, and enjoyed a modicum of international success with a short film (even including financial success – which was a surprise to him – he didn’t know that could happen with a short film). Turns out he has some storytelling chops, or at least a talent for making people laugh and/or cry.

Evidenced most keenly when he started seeing people react to Talking Mimes: it was not uncommon for the often highly emotional reactions to culminate in tears. He describes it as a strange cognitive dissonance. Feeling good about making someone cry – being at once concerned that he delivered some measure of trauma, but also gratified that the piece is working to full effect.

“You can see a similar dissonance play out in them too, as they tearfully recount how emotionally difficult it was, but at the same time talk about how wonderful it is and insist that all of their friends and colleagues go through it too,” says Stefan.

Less complicated is the delight he feels when it makes someone laugh. An important component of Talking Mimes are the moments of fun and dark humour – something that the disability community has in spades, and gushes just as freely from Stefan, whose short film was a dark comedy.

Part Three: Nothing about us, without us, all around us

In a better world, people, particularly people in power, would just listen directly to those with lived experiences. They would listen and act on the received insights and instructions about how to make the world universally accessible – to build a world free from systemic ableism and an able-bodied default measure (currently present everywhere from infrastructure to healthcare).

In the world we live in now, where few people listen and fewer act, we need to use tactics to capture attention and deliver messages that stick and drive change.

And as we know from personal experience, maintaining attention is hard. Harder still in the age of digital devices. Research suggests we average around 50% attention in a meeting or learning situation. The other half is “monkey grooming cat friend” videos and daydreaming about your next holiday. Virtual reality, though, forces you to attend and be fully present – everywhere you look and listen can be designed to deliver the message, and your digital devices can be silenced and put out of reach in actual reality.

Stefan is convinced of VR’s potential for good. “You can pack so many teachable moments into a virtual reality experience. And even the most egocentric of subjects can find their empathy ignited when they virtually embody another. Experiential learning has the power to be richer and stickier than traditional education methods.”

Part Four: An unexpected gift

A person with vision impairment can develop superhuman listening speeds. Parts of their cortex that would otherwise be used to process light are remapped for sound, allowing them to attain listening speeds of 800 words per minute. For comparison, the average person speaks at 120wpm and reads visually at around 250wpm.

To illustrate another beautiful example of strength from (perceived) weakness, you only have to look at Kiwi, David John O’Connor, who was paralysed from the neck down in a rock-climbing incident.

In his superb words; “If regaining my physical wholeness meant that I must lose the mental and emotional lessons I have learned through the suffering and anguish, I would not want to change. I am more complete and whole as a person now than at any time before my injury. I have achieved a knowledge of self that illuminates everything clearly. It is like a key that unlocks a chest full of priceless treasures. It is the paradox of my disability.”

While our “problems” can feel like barriers to the life we want to live, they needn’t be if society evolves to stop disabling people for their differences. They can also be a source of great strength.

To put things into perspective, and why this simulation is for everyone, stop and ruminate on the fact that almost all of us will have an access need at some point in our lives and we’ll be at the mercy of others. Whether that need stems from a mental or a physical ‘disability’, at the very least we’ll need educated empathy and compassionate behaviour from our fellow humans. Talking Mimes aims to better inform that behaviour towards those of us with these needs right now.

Through this 12-minute simulation, you can counter the ignorance and empathy deficit that is distressingly dominant in the human condition. Talking Mimes shows us how powerful a VR experience can be in closing that gap.

Interested in making more inclusive decisions? Find out more at talkingmimes.com.

five and dime is an ethical creative agency that shifts mindsets, changes behaviour and creates a better world through the power of storytelling. Changemakers they have worked with include the Ākina Foundation, Creative HQ, the Shift Foundation and the Zero Carbon Challenge. Curious about their work or know someone who’d make a good White Mirror story?

Visit fiveanddime.co.nz or get in touch at [email protected] or on 04 382 0510.