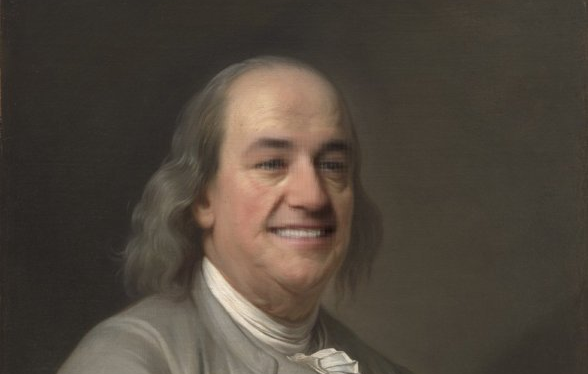

Tom White, senior lecturer in Victoria’s School of Design, has created Smilevector – a bot that examines images of people, then adds or removes smiles to their faces.

?? #NeuralPuppet pic.twitter.com/uuHqzujej1

— smile vector (@smilevector) October 22, 2016

“It has examined hundreds of thousands of faces to learn the difference between images, by finding relations and reapplying them,” he explains. “When the computer finds an image it looks to identify if the person is smiling or not. If there isn’t a smile, it adds one, but if there is a smile then it takes it away. It represents these changes as an animation, which moves parts of the face around, including crinkling and widening the eyes.”

— smile vector (@smilevector) November 13, 2016

— smile vector (@smilevector) November 14, 2016

?? #NeuralPuppet pic.twitter.com/z3bJdjU1Uy

— smile vector (@smilevector) October 21, 2016

OK, so it all sounds a bit quirky – but White swears there’s a serious purpose behind it. “These systems are domain independent, meaning you can do it with anything – from manipulating images of faces to shoes to chairs. It’s really fun and interesting to work in this space. There are lots of ideas to play around with.”

The creation of the bot was sparked by White’s research into creative intelligence. “Machine learning and artificial intelligence are starting to have implications for people in creative industries,” he says. “Some of these implications have to do with the computer’s capabilities, like completing mundane tasks so that people can complete higher level tasks. I’m interested in exploring what these systems are capable of doing but also how it changes what we think of as being creative is in the first place. Once you have a system that can automate processes, is that still a creative act? If you can make something a completely push of the button operation, does its meaning change?”

White says people have traditionally used creative tools by giving commands. “However, I think we’re moving toward more of a collaboration with computers – where there’s an intelligent system that’s making suggestions and helping steer the process. A lot will happen in this space in the next five to ten years, and now is the right time to progress. I also hope these techniques influence teaching over the long term as they become more mainstream.”

The paper Sampling Generative Networks describing this research is available as an arXiv preprint. The research will also be presented as part of the Neural Information Processing Systems conference in Spain and Generative Art conference in Italy in December.

As good-natured as White’s project seems, it’s also worth noting how easily automation can also go wrong. In 2015, Coca-Cola had to shut down its #MakeItHappy chatbot after it began to tweet passages from Mein Kampf.

#MakeItHappy is far from the only chatbot that’s had problems. Earlier this year, Microsoft launched Tay, a chatbot intended to answer questions via Twitter in the manner of a teen girl. Tay was taken offline in just 24 hours, after it horrified its creators when it began spewing profanity-laden racial epithets and talking endlessly about graphic sex acts while praising Hitler and proclaiming the US government was behind 9/11. Microsoft blamed the whole thing on internet trolls who “taught” Tay.

The issues aren’t limited to chatbots. In November, a robot named “Little Fatty” designed to interact with children aged between the ages of four and 12 went berserk at a Chinese tech fair after answering questions. During its rampage, Little Fatty rammed a display booth and drove into a visitor. One man was hospitalised as a result. Even creepier, when workers finally brought Little Fatty under control, the robot reportedly made an “unhappy” face.

Little Fatty.

Even IBM’s famed Watson has had its issues. About five years ago, an IBM research scientist attempted to teach Watson slang by uploading the entire Urban Dictionary. As a result, Watson began to curse and even use racial slurs when responding to questions.

Slightly less sinister, the WTF Is That Bot was designed to identify what’s in photos sent to it. Unfortunately, its results have been less than accurate.

Although not as spectacular a failure as Tay, Microsoft has struggled with photo identification automation, too. Your Face was designed to “provide a frank assessment of your face.” Idealog tried it out – and we weren’t exactly impressed.

Some of Idealog’s interactions with Your Face.

The takeaway here: as charming as the Smilevector seems, the reality is that automation has a ways to go before we can view it as something capable of showing respect – or even basic manners.