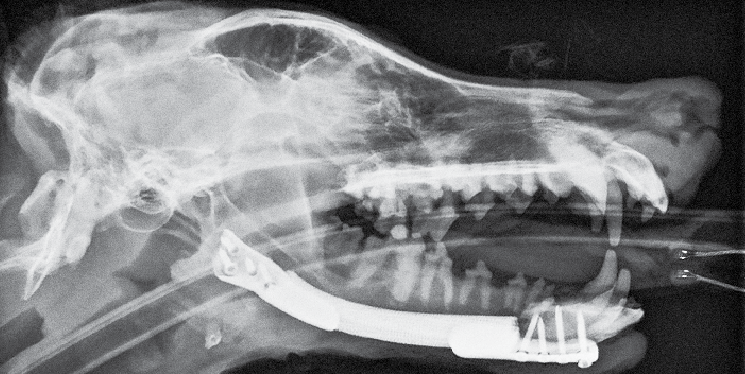

Last year, Warwick Downing got a visit from a TV crew making a story for Canadian television about a Canadian cat with jaw cancer getting a titanium implant to replace the diseased bone. The custom-made titanium part was being made, not in North America, but at Downing’s company Rapid Advanced Manufacturing in Tauranga, using CAD files generated from CT scans of the cat’s jaw. Once printed, the part was sent to Canada for the operation, saving the cat’s life.

Titanium body implants aren’t that uncommon these days. Titanium is bio-compatible, non-toxic, doesn’t rust in the body, and has a good strength-to-weight ratio. But what Downing’s company can do that many other companies (even countries) can’t, is custom-3D print titanium from CAD files, so the implant fits the recipient exactly, improving outcomes and surgical time.

RAM trialled its first artificial dog jawbone in mid-2013, working with Hawke’s Bay design company Axia and Massey University vet surgeons to save the life of a boxer dog with aggressive mouth cancer. Downing’s company printed the titanium jawbone on Tuesday, it was fitted to the dog on Wednesday and 12 hours later, the animal was eating happily.

Since then, RAM has done more animal implants, including leg and hip bones. And in June last year, it 3D printed part of a titanium human jawbone, for a ground-breaking operation on a 32-year-old in Australia.

“We have done a handful of human implants, mostly into Australia,” Downing says, “but this is just a precursor of what we will be able to do, creating really cost-effective parts designed for individual patients. At the moment we are being held up [from doing further human implants] by regulation, but I’d like to see New Zealand being competitive internationally across the customised and semi-customised implant market.”

A handful of crushed titanium

Madeleine Martin, general manager of Christchurch-based Ossis Custom Orthopaedic Solutions, which uses 3D printing to make custom titanium bone implants, says although off-the-shelf implants are common, they don’t always fit the patient’s problem.

“Our company works with surgeons who have very complex problems to deal with. The organic shape of the 3D printing allows us to create custom devices that better suit patients.”

She says New Zealand is at the forefront of the custom implant field. “Internationally, quite a few companies are starting to use 3D printing for off-the-shelf implants, but very few companies use a custom method, and even fewer pair a custom method with 3D printing. We have one key competitor in Belgium. But they don’t have the longevity or experience that we do.”

How New Zealand got to be at the forefront of 3D printed metals comes down to a group of about eight far-sighted engineering, research and manufacturing companies in the Bay of Plenty who got together in the late-‘90s to explore 3D printing with metals.

“A group of people thought there was a lot happening in powder metallurgy, but New Zealand was not taking advantage of it,” says Downing, who is also CEO and founder of TiDA Ltd, a company doing research and product development based on powdered metals.

“We worked together to buy New Zealand’s very first metal-printing machine. At the time it cost well over a million dollars and was one of only about 10 machines in the world that could do it.

“The beauty of being in Tauranga was that a lot of business people knew each other and said, ‘Let’s give it a go’. We put money in, got support from NZTE and that was the basis of getting the industry started – people with a vision that we could do things differently. We were right at the forefront of 3D printing internationally – we got out of the starting blocks early.”

These days, RAM has four 3D metal printers on site and about 150 clients for its 3D printing services, of which about 10% are still in the Bay of Plenty. About 30% of RAM’s business is in titanium, and 5%-10% of revenue is from export.

“We’ve managed to build a global reputation for developing this technology. For example, we have people coming down from Boeing to visit us.

Everyone thought Australia must be well ahead, but we’ve got more 3D printing machines operating commercially, and more activity. They are trying to replicate what we do, over in Australia.”

Downing says the main disadvantage of titanium has traditionally been its cost, and the fact it is “horribly, horribly, terrible to machine”. 3D printing resolves the machining problem, and makes titanium more cost effective by eliminating waste. He says 3D printing is particularly good for making intricate shapes and structures, and increasingly companies are using it for anything from taps to jewellery to aircraft parts.

One of Rapid Advanced Manufacturing’s customers is Mt Maunganui-based Oceania Defence, which uses titanium for its gun silencers to reduce weight. Another company, Kiwi Klimbers, is making climbing spikes to help arborists get up trees. Upmarket London store Harrods stocks scissors made by a New Zealand designer and printed at RAM, and Auckland furniture and lighting studio YS Collective 3D prints parts for some of its pieces.

A Victory Knives knife

John Bamford, managing director at Auckland’s Victory Knives, says most of the company’s knives are steel, but it started thinking about titanium after an approach from yachting syndicate Team New Zealand before the last America’s Cup campaign.

“The team had other sailing knives but they weren’t happy with them. They said to us, ‘If you can come up with something better we’d love it’. We already had a relationship with Warwick [Downing] and TiDA developing titanium knives using 3D Printing. When Team New Zealand got keen, everyone got keen. It went from not even an idea to a fully-fledged working prototype in under a month.”

Still, until prices come down, making knives from titanium isn’t going to be a mainstream part of Victory’s business, Bamford says.

“It’s a great way to print a knife quickly, but as a full-on production process, 3D printing is expensive. Most sailors won’t spend $400 on a knife. There will be a tipping point soon where it becomes economical for us, but at the moment it’s a bit too niche to have a significant impact on the knife world.”

***

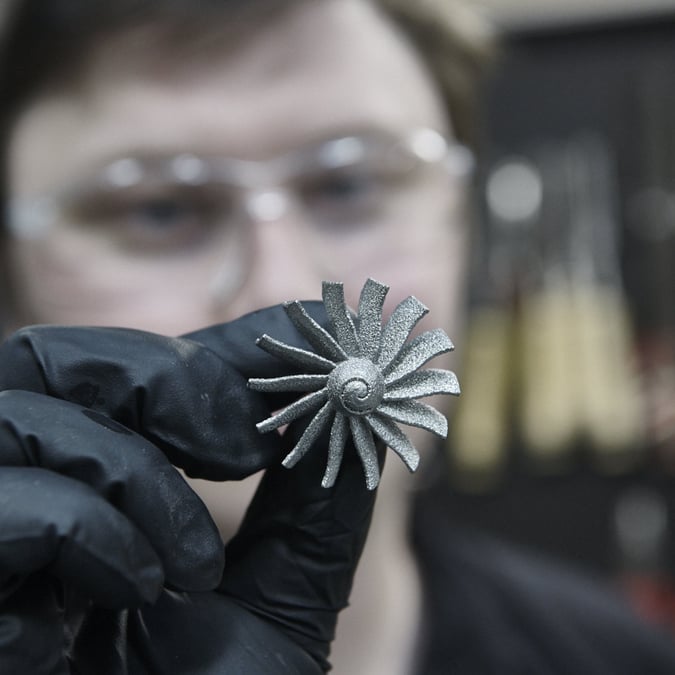

So, how do you 3D print titanium?

Most of us have seen a 3D printing machine make little plastic things. It’s like a glue gun on steroids shooting resin, which builds up into an object. 3D printing metal is different. For a start, instead of building upwards, the process used by RAM and others (called ‘selective laser melting’) builds the object downwards. Imagine a bed of fine sand (the titanium powder). The computer-generated design breaks the object to be printed into thin layers. To print each layer, a laser melts the titanium powder on the bed to match the pattern for that layer. The fused powder layer then drops down fractionally and the printer spreads a new layer of titanium powder over the top of the previous layer. The laser then fuses that layer of powder onto the layer below it. And so on.

***

Titanium everything

Warwick Downing says most people think 3D printing only has a small number of applications, and is limited to the biomedical and aerospace industries.

“But as soon as you put complexity into a design, this technology will come into its own,” he says. “It is quite versatile and it’s certainly not restricted by the industry.”

With those words ringing in our bionic ears, we found a few other things being printed in titanium.

Bikes

Titanium is light and strong so in 2014, Empire Cycles, a British manufacturer that makes high-end bikes, engineered the world’s first 3D-printed titanium mountain bike.

Eyewear

Hoet is a Belgian eyewear company using 3D printing to make highly customised, very sexy titanium specs.

Earphones

Japanese hi-fi company Final Audio Design, with the help of a few others, designed and created the world’s first mass-produced 3D-printed titanium earphones. Plastic? Pffff.

Overpriced ornaments

i.materialise offers anyone the opportunity to buy 3D printed titanium objects or have their own designs created—for a fairly hefty fee. Your mantelpiece never looked so good.