If you pay for something, it’s the product, but if you don’t, you’re the product, writes Vaughn Davis (who is not the product. Wait, what?)

I’m writing another book. Well, to be honest, I haven’t gotten very far with it, but it does have a name and I’ve even mocked up a cover (red leather, gold embossed in a soothing serif font, naturally).

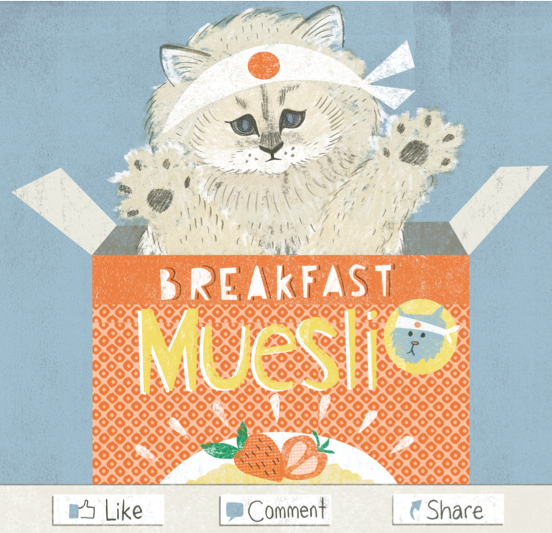

ILLUSTRATION: Angela Keoghan

My book is about privacy on the internet, and the implicit and explicit contracts we enter into every time we use an online service.

It provides a perspective on our rights as users, and the extent to which a service provider should and shouldn’t use information about our profile, network and online behaviour for commercial gain. My book is called You Ticked The Fucking Box, People.

I think it’s a rather good title. (So good, in fact, that I really can’t see what needs adding in terms of actual chapters and suchlike, hence I haven’t written any. My publisher is unimpressed.)

Of course, ticking the box doesn’t even come close to meaning we actually read the 80 pages of conditions that preceded it, but that’s another story, and one that was told excellently and scatologically in the South Park episode The Human CentiPad. (As was impressively pointed out to me by Privacy Commissioner John Edwards as I was researching this column.)

But back to my book. There’s a saying in the online world that if you pay for something, it’s the product, but if you don’t, you’re the product. (While it’s recently become popular again, it dates back to at least 1999. No one really sure who said it first.)

It’s probably not as black and white as that, but the value equation is pretty clear and pretty obvious to most people. A web service such as a social network is provided free of charge, in order for the owner to capture your behaviour and sell that information to advertisers.

It’s hardly a new idea. That free local newspaper that comes through your letterbox is, of course, just a way of delivering your relevant local eyeballs to the plumbers, cat minders and supermarket owners whose ads finance the paper. All the online world does is allows those eyeballs to become even more relevant, by keeping close tabs on everything you do on the platform.

And even speaking as a human, not an ad guy, I’m perfectly OK with this. It’s the deal. It’s how that works. I get to use Google – Google! – the most powerful way in the history of our species to find pictures of Japanese cats in cereal boxes – free of charge. But every time I search for those cats, Google learns a little more about me and uses that knowledge to sell my preferences to advertisers. Every one of my 50,000 tweets adds a little to the sum of knowledge Twitter is beginning to use to slip ads into what I naively call ‘my’ Twitter feed. And every day of my online life I live on Facebook gives Mr Zuckerberg’s algorithm a more chillingly accurate picture of who I am.

Last Valentine’s Day, for example, Facebook data scientists released a cute piece of research showing they could predict the exact moment a couple would change their relationship statuses from ‘single’ to ‘in a relationship’, based solely on the frequency of public messages the couple posted to each other’s walls. They also had a study that had worked out when couples would break up, but were kind enough not to release that one at the same time.

And if they can do that, then knowing when we’ll be receptive to an ad for KFC, or cheap Ray Bans, or Hot Russian Brides is child’s play. And I’m OK with that. After all, I ticked the box.