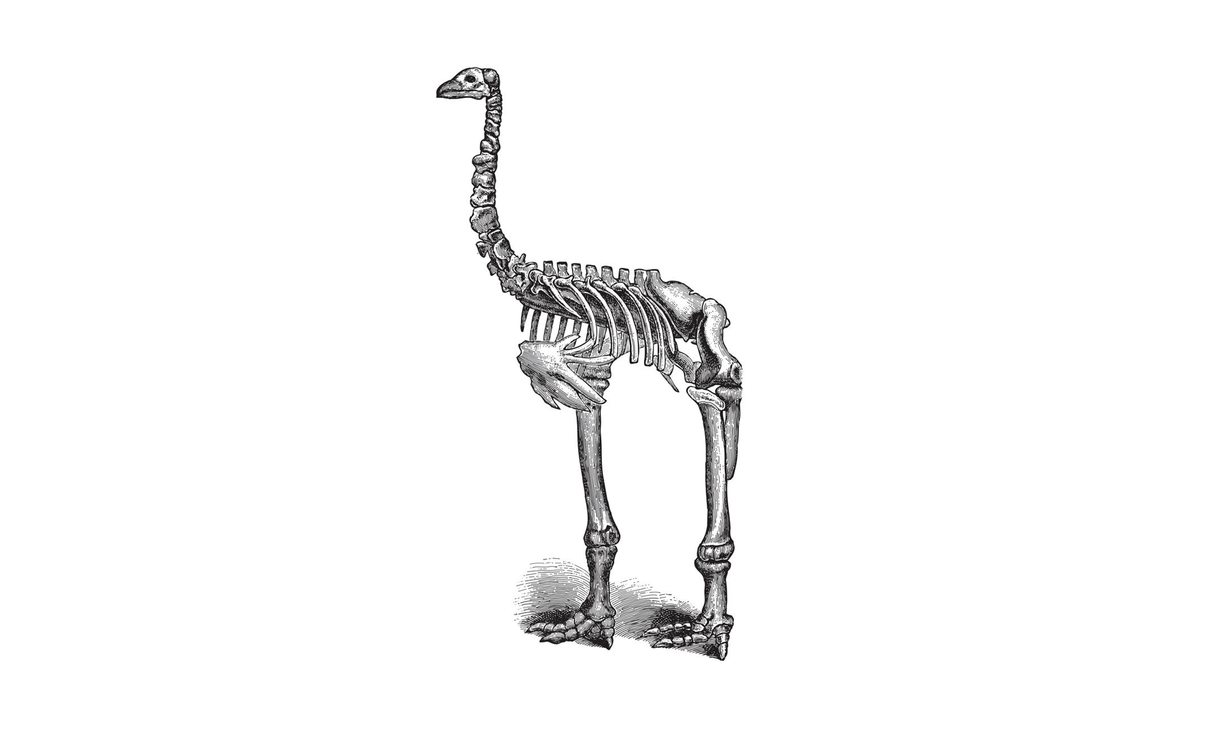

The de-extinction dilemma: should we bring back the moa or save the kiwi?

De-extinction – resurrecting extinct species with the help of modern technology – has been largely confined to the realms of sci-fi. But now technology is catching up with the fantasy.

Just a couple of years ago Labour MP Trevor Mallard was widely mocked for his “absolutely serious” suggestion that we could reintroduce the moa to forests on the outskirts of Wellington. Mallard’s idea was treated as a bit of a political joke at the time, but government may soon have to give due consideration to such proposals and weigh up the cost and benefits of bringing back New Zealand’s lost species.

Conservation costs

The idea that we could bring back the moa, or the huia or the Waitomo frog, will certainly be exciting to some. But when such initiatives become possible, it will cost money. Lots of money. Undoubtedly the question will arise: who pays? And could that money be better spent elsewhere?

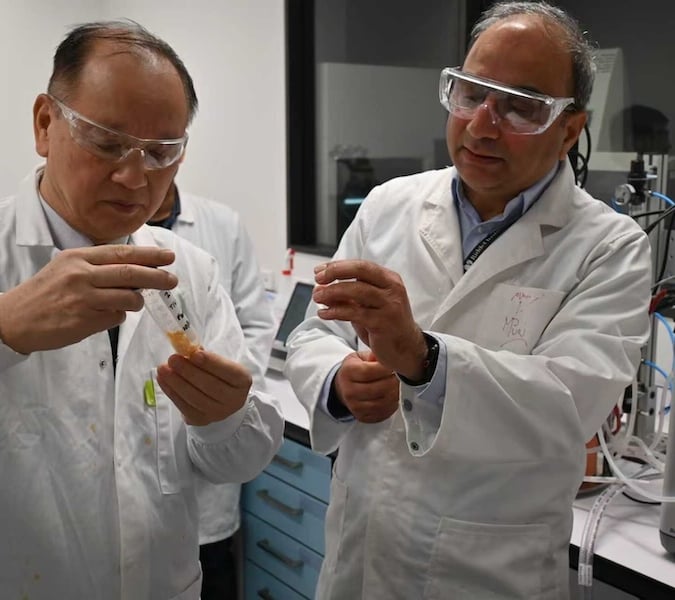

The conservation costs of de-extinction are laid out in a study recently published in Nature Ecology & Evolution. The authors – including scientists from DOC and the universities of Otago and Canterbury – examined how much it would cost governments to establish and maintain wild populations of likely de-extinction candidates.

The little bush moa, South Island snipe and long-billed wren were among the 11 extinct NZ plants and animals considered in the research, alongside five species in New South Wales, Australia. The conservation costs for these species were estimated by looking at similar, living species. For instance, the annual conservation bill for the little bush moa was estimated to be a cool $359,560, based on conservation costs of kiwi. The analysis specifically excluded the costs of actually re-creating the species, but did take into account any co-benefits protecting resurrected species might have for other natives – e.g. increased predator control.

‘Net biodiversity loss’

Even with these pretty optimistic assumptions, the authors found that if the government were to take on responsibility for protecting resurrected species, it could have a negative impact on other native species by stealing away precious financial resources. If the Department of Conservation were to foot the bill for looking after all eleven freshly ‘de-extinct-ed’ NZ species it would need to sacrifice funding for nearly three times as many – 31 – other native species.

If the costs of looking after resurrected species were covered by a well-meaning private agency it might work out better for other natives due to the shared conservation effort, but the authors note:

“However, the potential biodiversity benefits are outweighed by the opportunity costs of not applying the same funding to extant species.”

They conclude:

“Our analysis strongly suggests that resources expended on long-term conservation of resurrected species could easily lead to net biodiversity loss, compared with spending the same resources on extant species.”

De-extinction: not just about money?

In commentary accompanying the research, Ronald Sandler, an Associate Professor of Philosophy at Northeastern University, welcomed the research but cautioned against just focusing on biodiversity versus dollars and cents. Cost benefit analyses would be useful in evaluating candidate de-extinctions, he said, but they should not have the final say on whether a de-extinction ought to proceed:

In commentary accompanying the research, Ronald Sandler, an Associate Professor of Philosophy at Northeastern University, welcomed the research but cautioned against just focusing on biodiversity versus dollars and cents. Cost benefit analyses would be useful in evaluating candidate de-extinctions, he said, but they should not have the final say on whether a de-extinction ought to proceed:

“What is needed for de-extinction… is development of inclusive decision-making frameworks that situate cost–benefit analysis as one important consideration among many goods and values that might be at stake, such as cultural value, environmental rights, justice, intrinsic value and aesthetics.”

Such wider benefits of de-extinction certainly factored in moa fan Trevor Mallard’s straight-faced calls to bring back the species: tourism, scientific achievement and international recognition were among his reasons for returning the extinct bird to New Zealand forests.

“We could again see a snapshot of New Zealand as it once was before the arrival of humans. I know that this all sounds a bit like a scene from Jurassic Park. But it is going to happen.”

“The moa will be a goer.”

-

This was originally published on Sciblogs.