Morgan Godfery on the new popularism, the politics of love and his new book, The Interregnum: Rethinking New Zealand

“Imagine a French peasant in 1787, one who is convinced that kings will rule in perpetuity, feudal lords will always starve the masses, and bishops will forever be at their intrigues,” Morgan Godfery writes in his introductory essay to The Interregnum: Rethinking New Zealand, a book he’s edited containing ten essays from New Zealand writers on the possible futures of politics in New Zealand.

“The peasant will have at his or her side the authority of history, the overpowering knowledge that nothing has changed in centuries. But he or she would be wrong about the direction history is travelling.”

Godfery and the book’s contributors argue that we (in New Zealand and elsewhere) are at a point in history where the neoliberal political consensus of the last 30-or-so years is beginning to break down without a new dominant ideology coming to take its place. This moment of uncertainty, the book argues, is an opportunity to reconsider our assumptions and rethinking of our values.

“It is up to us,” Godfery writes, “to ensure that history travels towards justice – and love.”

Image: Morgan Godfery, c/o Twitter

Idealog talks to Godfery about the book, where we’ve been and where we might be headed.

To start at the beginning, what is the ‘interregnum’?

It has an interesting linguistic history. It used to refer to the moment between the death of one sovereign and the enthronement of another. But in the 1920’s, Antonio Gramsci, writing from prison, subversively used the word to refer to the space between dominant ideologies or the moment between political discontent and political change. He was referring to all the big transformations happening outside his prison walls in Italy – the rise of fascism and communism in the country and the pushback against that. That’s how we use the term – that ambiguous moment between political protest, political discontent, and then actual change.

What’s the period that’s ending, or, to use the book’s subtitle, what’s the New Zealand that’s being rethought?

The argument is that the political settlement of the last 30 years, whether you call it Rogernomics or neoliberalism or the free market, that definitely period of New Zealand history is coming to a close and there’s intense and growing debate about what takes its place.

So we see the free trade consensus beginning to fray with the anti-TPPA movement and all these other dramatic changes beginning to happen in New Zealand which signal that we’re entering that space between dominant ideology and political protest, and discontent and actual change.

You probably see it in the US a bit clearer with the rise of Bernie Sanders and his democratic socialism and Donald Trump and his capitalist authoritarianism, and those two ideologies battling it out.

That’s an interesting dynamic in that both of them come from a similar space, where Trump is obviously very protectionist, he’s appealing to people where a lot of jobs have been lost to free trade. We haven’t had that political figure here yet. Over the last 30 years there’s been a convergence in the centre, particularly in the last 15 years with Helen Clark taking Labour towards the centre, and that in turn forced National to move to the centre too. The Green party, widely thought of as the most leftist party, is positioning itself as a business-friendly, ecological alternative to both Labour and National…

What’s interesting is that the Labour party is making movements to the left. Bryce Edwards called their tertiary education policy a “return to radicalism”, and just yesterday we saw Andrew Little calling for a debate around a universal basic income [UBI], which is probably the most left-wing proposal from the Labour party that we’ve seen since before the David Lange era.

But it’s an interesting point about Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders – very different solutions but they emerge from that same social trauma – the loss of jobs. And they talk about the same things – trade deals that lead to off-shoring, and a healthcare system that doesn’t provide for a high number of Americans. They’re tapping into the same insecurities and proposing very different solutions to it, which is fascinating.

It seems like another sign of the interregnum, a battle between these two competing ideas which come from the same place.

You use the February anti-TPPA protest in Auckland as a symbolic event. Do you see that activism turning into a more practical, electoratoral politics? Where do you see that energy going?

It’s interesting because the movement hasn’t cohered into an electoral force, they’re not pushing the Labour party or the Greens to do something radical. It’s very much still a street-level movement, which is interesting because that’s exactly how the anti-war movement in the UK started under the New Labour government. It was very much a street-level movement until very recently when it got behind Jeremy Corbyn. The anti-war movement was instrumental in catapulting him to the Labour leadership and evolving into this group Momentum, which has formed to keep him there.

It’s really interesting to see whether the TPPA movement does a similar thing – do they get behind an electoral force and try and catapult him or her into a position of power, or do they remain a street-movement and try and protest and bring attention to that issue?

It’s an interesting dynamic because if you buy the thesis that we’re in the interregnum, you can’t actually answer where it goes from here, because it is an uncertain space where we have all this political energy and movement but no one’s actually certain where it goes.

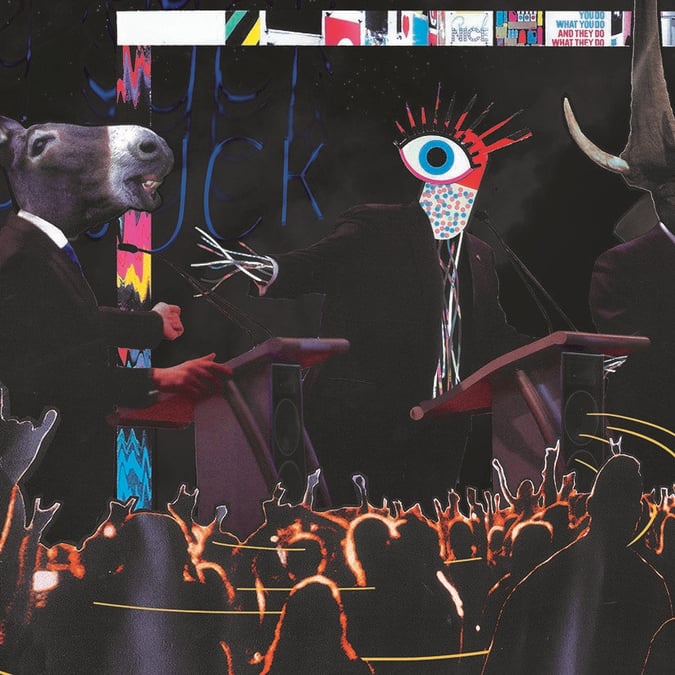

Image: TPPA protest c/o ActionStation

What are the book’s proposals? Is there a linkage between them? Was that the pitch, looking for proposals as to what comes next?

Yeah, that was basically it – approaching ten New Zealanders and asking them how they feel about the future and what they think comes next. And do they even think we’re entering the interregnum?

And I found it interesting that they all said ‘Yes’, which is a comment on things in itself that these ten New Zealanders, some of them not even in New Zealand, but doing very smart things overseas, agree that things aren’t quite right, that wealth inequality is growing, that secure work is going. To agree on those and then discuss how we go forward was quite interesting.

The thing that connected each piece was love, which wasn’t by design and was actually quite surprising. Everyone knew Max [Harris] was looking at the politics of love but everyone, without direction, chose love as the value to underpin their thinking, which I thought was a very interesting shift. People weren’t looking at those traditional policy values, such as efficiency (to give a bad example), they were looking to something that we don’t usually associate with politics but with our personal lives, which was fascinating.

And we see Hillary Clinton kind of doing the same. Just last week she made a speech calling for love to “make America whole again”, which was set up in explicit opposition to Donald Trump’s call for strength to “make America great again”. Which was an interesting signal that maybe this idea of love in politics has greater salience than people might have thought.

Another theme in some of the essays is the way that the neoliberal economy has changed the way we live and interact, the way we see ourselves. Increasingly, our work is us and we’re always working. We’re our own brands. Increasingly, we’re less tied to specific employers, less tied to a specific career. We’re tied to the value we create in ourselves. It might seem like a crass term, though I don’t mean it in a crass way, but people’s ‘personal brand’ is important to the value of their labour now, whether you want it to be or not. If you’re a writer, for example, you’re no longer a representative of a publication, you’re a brand that is affiliated with your publication’s brand. The publication is almost a qualifier. You seem to work in that mold, as someone who’s becoming, or has become, a public figure. How do you feel about that as someone in the public sphere, as someone who has edited a book on a very public question?

I find it pretty difficult. Because you can’t opt out. Once you’re in, you can opt out because there’s always pressure. I think I use the term ‘competitive positioning’ in the book, there’s always pressure to be in the right position, to not be compromising earning time. That individual focus, Max [Harris] says it leads to loneliness, and I tend to agree because you’re always focusing on what comes next for me or how am I going to pay next week’s bill? What’s my freelance income going to be this month? Which puts pressure on you to only think about yourself because you simply don’t have time or the means or the support to actually think about other things, whether that’s politics or rebuilding a collective state, which might make things easier, or UBI, which would give you time to actually do this you might want to do rather than just how to survive week-to-week or month-to-month or year-to-year.

What are the the aspects of the moment you’re talking about that the book doesn’t discuss?

There’s an interesting counterpoint to the whole book that might be worth mentioning. We’re here talking about disruption and what comes next but we haven’t explored this feeling of resignation, we talk about the economic changes of the last 30 years and how that’s leading to disruption, but we didn’t actually deal with how that’s caused resignation as well. You see it in voter turnout for young people, which is abysmal. And we haven’t dealt with how that works and how you overcome that. We all make the assumption that that has happened because the economic changes of the last 30 years have lead to a more atomised society so people have checked out of politics because they don’t have the time or because they’re disillusioned, but we haven’t actually dealt with how you overcome that, or we haven’t actually even tested whether that theory is true. We make the assumption, but I think it’s a real blind spot in everyone’s understanding – the government doesn’t know, the political parties don’t know, we don’t know.

What’s your thinking on that?

My pet theory is that people have checked out because they’re disillusioned. They don’t think that change can happen. They think that change goes in the opposite direction to their needs – weakening of worker’s rights, weakening of the social safety net. But we haven’t seen anything to replace that. If you’re going to weaken workers rights, you should also increase opportunities for education, but at the same time as we weakened workers rights we actually introduced a fee paying tertiary education system. And it hasn’t worked out for many. In the 1980s Roger Douglas and Ruth Richardson promised, ‘We’ll make your work insecure, but we’ll make transition to new work easier’, but that never worked out. I think that’s where it comes from, that social trauma from the ’80s and ’90s. People have checked out and thought, ‘We can’t trust politicians’, or ‘politics can’t really do anything for us’.

The books ends optimistically, with Max Harris’ ‘The Politics of Love. Are you optimistic?

Yeah, yeah. Definitely. You can’t afford not to be. I’m optimistic for change. Looking overseas and looking at the new populisms – Jeremy Corbyn, Bernie Sanders, not so much Donald Trump, but Podemos, Syriza, Die Linke, all these different movements challenging the status and not taking us back to where we were, but trying to restore a sense of stability and security to people’s lives. That’s certainly what the new populisms to the right – UKIP and to a certain extent Donald Trump – are doing as well, tapping into people’s want for security and stability. Which one wins out – whether it’s Bernie Sanders or Donald Trump – is where the danger is, but we’re travelling in the right direction.