Half a century ago at Victoria University of Wellington, a radical new school set out to reinvent design education in New Zealand. Since then, it has transformed careers and reshaped the way the nation designs, builds and lives. Robyn Phipps, dean of the faculty of architecture and design innovation, looks at how its groundbreaking approach helped spark Aotearoa’s culture of innovation and urban creativity.

In 1975, as oil shocks unsettled economies and the space race reshaped how people imagined the future, Te Herenga Waka – Victoria University opened an architecture school that responded to the times with a bold experiment.

It was founded on the conviction that design could not stand apart from science and technology. Decades ahead of their time, staff placed thermal performance and sustainability at the core, and elevated physics, structure and materials from supporting subjects to central forces sparking new approaches to the built environment.

This was a contrast to Auckland’s long-established programme, which drew on the traditional Beaux-Arts model of studio training and professional practice. Wellington complemented that by reorienting the field toward science and technology as creative drivers of design.

Half a century on, the spirit of that experiment endures in the extraordinary breadth of its graduates, whose work spans city skylines, industries, technology and ideas that reach far beyond New Zealand.

A radical departure

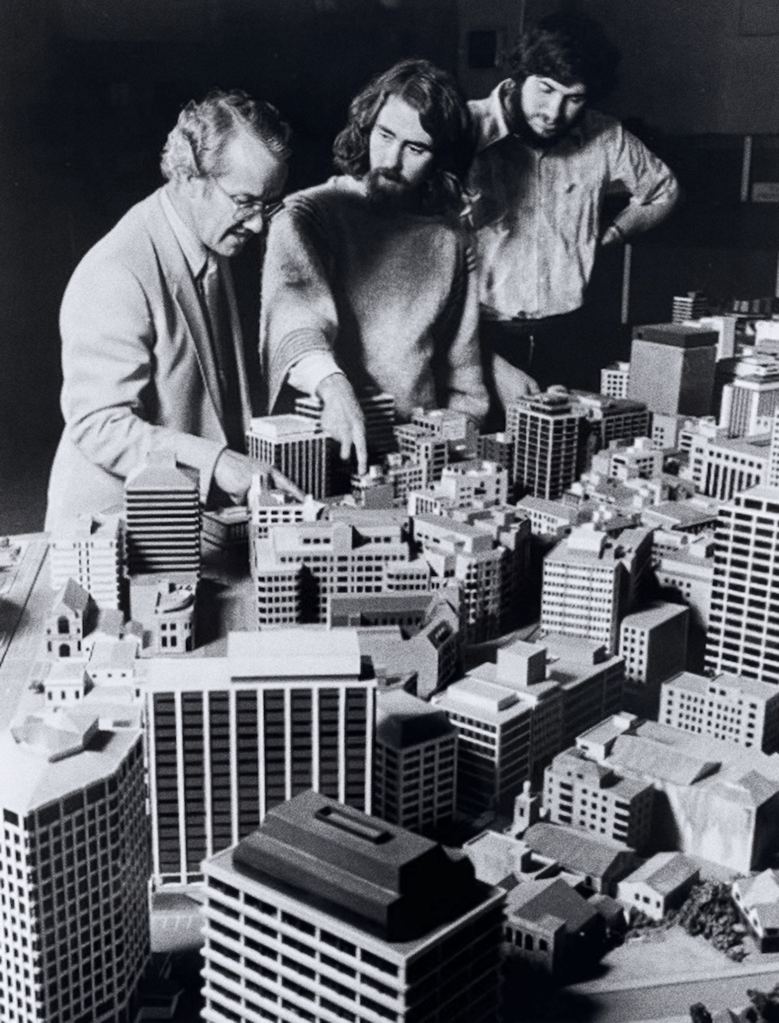

Wellington’s break with tradition was a deliberate choice. Founding professor Gerd Block drew on international reform movements of the 1950s and 1960s, particularly the 1958 Oxford Conference on architectural education, which urged schools to ground their teaching in science and evidence.

Block assembled a faculty of engineers, scientists and designers in services, structure, lighting and building science. The team included John Gray, who taught communication and helped students articulate ideas as well as draw them; structural engineer John Webster; design theorist John Daish; and architect Wendy Light, recognised for her innovative use of colour.

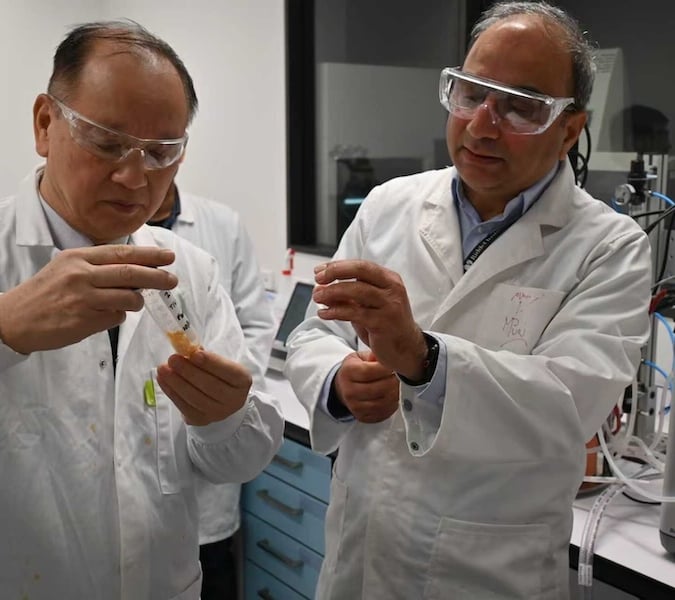

Within building science itself, three strands took shape: structures led by John Webster, construction by Tom Jarman and environmental services developed by George Baird and Kit Cuttle. George focused on heating and ventilation, while Kit developed lighting and acoustics. Research funding George secured enabled him to bring in a young physics graduate, Mike Donn, to join the work.

The mix was unconventional, with no discipline dominant, giving students perspectives they never expected in an architecture school. Lighting specialist Kit Cuttle, one of the original building science staff, recalled Block’s conviction: “Students can only draw pictures until they understand the science of building. They need this to truly understand design.”

Different from the start

From the outset, the school looked and felt different. It resembled less a traditional atelier and more a working laboratory. Barry Pearce, a founding staff member with a background bridging engineering and architecture, highlights how different the approach was: “Wellington stood out because it treated technology as something to inspire design. The aim was to get students to love technology, not fear it.”

That philosophy was visible everywhere. Studios were stacked with wind-tunnel models, daylighting rigs, acoustic testing gear and thermal mock-ups. In one corner, students might be experimenting with giant icosahedrons and space grid structures. Everywhere you looked, instruments of science doubled as tools of creativity.

A school of its place and time

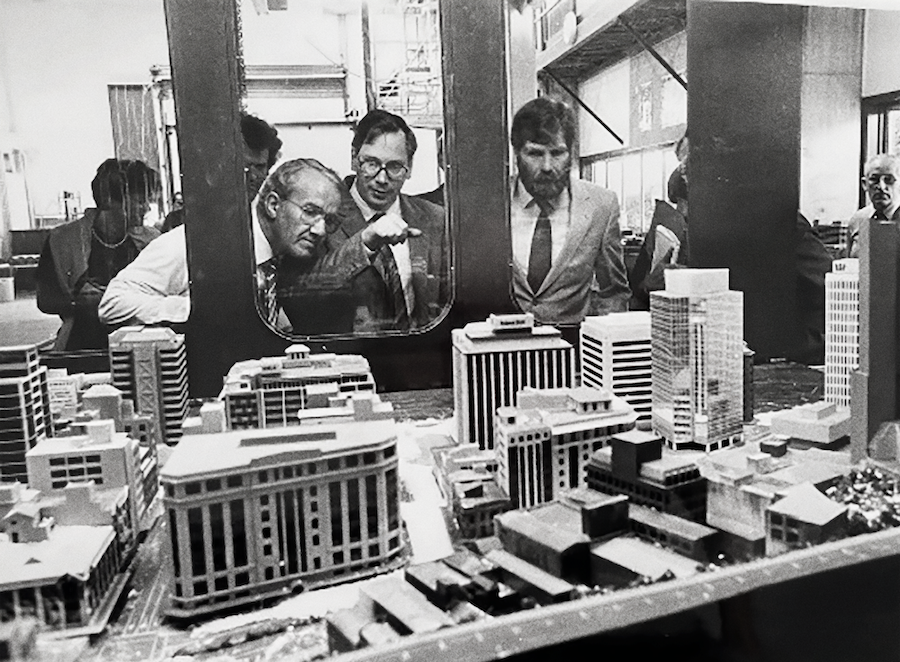

In Wellington, the concentration of government agencies, research institutions and technical specialists flowed straight into life at the new school, turning the city itself into an extended classroom.

George Baird, one of the founding staff and head of building science, remembers the capital as “a special kind of place” where the department of scientific and industrial research, the ministry of works and development, the government architects, the education board, and the building research bureau were all within reach of the school.

Students tested seismic performance with earthquake researchers, drew on Building Research Association of New Zealand (BRANZ) data for building performance, learned plate tectonics from geologists years before most schools overseas and absorbed ergonomics insights from Wellington Polytechnic.

The 1970s also brought global and social upheaval that shaped the curriculum. Energy crises made efficiency and environmental performance urgent, with staff embedding these lessons into teaching years before many other schools did – a move that helped transform building standards in New Zealand, improving both costs and public health.

It was, as Pearce recalls, “a very exciting time to be starting a school,” an era in which the space race, molecular science and new geometries were reshaping how people understood the world around them. The Wellington school absorbed all that energy, treating technology not as a means to an end but as a spark for ideas and inspiration.

An egalitarian culture

From the outset, Wellington widened the doorway into architecture. Where other architecture programmes were built around the authority of master architects, students were expected to rigorously test and assess ideas, challenge assumptions and work across multiple disciplines to reach well-considered and imaginative design outcomes.

This ethos extended to admissions. Entry was tough, relying on solid grades in maths and science during the pre-entry intermediate year, rather than solely on a portfolio. Students could also enter directly from a science degree pathway, bringing a technical depth that further enriched the school’s design culture.

In 1978, Gerd Block invited Helen Tippett, at the time the acting head of the school of building at Melbourne University, to become the school’s second professor and later dean of architecture at Victoria, making her the first female professor of architecture in Australasia. In Wellington, Tippett continued the work of building bridges across policy, industry and research.

She was active on the BRANZ Board, became the first woman to lead the NZIA and was a founding member of the New Zealand Institute of Building. At university level she represented the interests of the new school and encouraged multi-disciplinary cooperation, influencing the school’s outward-looking identity.

Tippett championed inclusivity, respecting Māori perspectives at a time when this was new in universities, and worked to broaden opportunities for a wider range of students. Tippett’s approach to teaching was also personal. As her daughter Victoria recalls: “She would invite whole first-year classes to our home as part of their orientation, so she could get to know them.”

Hard-won recognition

The early years were not without challenges. Even inside Victoria, some questioned whether architecture belonged in a university at all. One university figure allegedly dismissed the school as a “carbuncle on the side of the university.”

That made external recognition crucial. In 1979, the school underwent its first full accreditation by the New Zealand institute of architects and the commonwealth association of architects. For a week, the visiting board examined teaching, facilities and student work.

The outcome was decisive, with full approval for five years rather than a provisional nod. It was, as George Baird recalls, the moment the bold experiment proved itself and lifted the school’s profile both nationally and internationally.

Design innovation arrives

In 1999, Victoria University took the next step in broadening its experiment. A school of design was established alongside architecture, and in 2017 they jointly became the faculty of architecture and design. New degrees soon followed in industrial design, digital media and other fields, carrying the founding ethos of integration into territory far beyond the built environment.

What began as an architecture school became a hub for creative disciplines at every scale. Students now move easily between urban systems, buildings, products and digital interfaces, always with performance, sustainability and human experience at the centre.

Today, the faculty of architecture and design innovation (FADI) includes landscape architecture, industrial design, digital media, interior architecture, building science, fashion design, interaction design, construction management, construction health and safety, construction law and building surveying, and many more majors.

The university describes it as “a leading provider of innovative education in design and the built environment.” It also cooperates internationally, with a thriving joint institute with Zhengzhou University that delivers degrees in architecture, landscape architecture and industrial design.

A living legacy

Half a century on from 1975, the experiment that began with 25 students has grown into a living legacy. While many alumni are making their mark in all corners of the globe, there is also a strong contingent crafting world-class designs and winning international awards from offices located in the Te Aro basin, strengthening Wellington’s claim as the creative capital of the world.

FADI graduates dream up cities, push the boundaries of sustainable designs, prototype futures and create entirely new technologies. Their work ranges from nuclear fusion labs to alpine resorts, from prosthetics reinvented through digital manufacturing to new town precincts.

On stage and the world stage

Some are shaping the look and feel of popular culture through film, stage and digital media, while others continue to advance architecture and the built environment across New Zealand and globally.

What connects these pathways is not a single profession, but a shared mindset. The spirit of experimentation and collaboration that defined the school in 1975 still drives its graduates today and lives on in Paparahi – the pathways and tracks they continue to forge across disciplines, industries and cultures.

Fifty years on, the experiment is still evolving. Paparahi: 50 Years of Architecture and Design Innovation runs from October 24-26 at Te Herenga Waka’s Te Aro campus, with an exhibition and public symposium celebrating the people, ideas and projects that shaped and continue to shape New Zealand design.