How The Britomart Foundation is transforming the lower CBD with public art

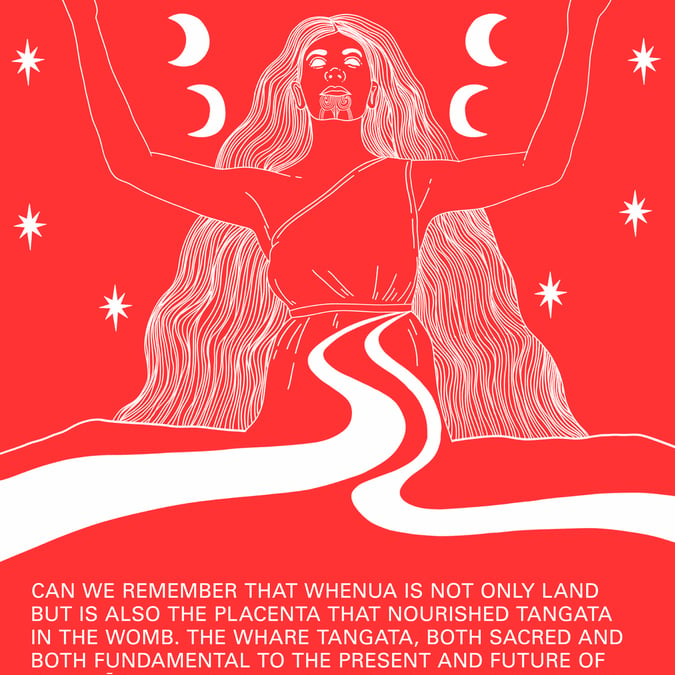

Tracey Tawhiao (Ng?i te Rangi, Whakat?hea, Ng?ti T?wharetoa) represents the first artist to participate in the series. Tawhiao’s artworks turn ugly media narratives into intricate paintings of positivity and are complemented with her words to help onlookers understand the message the artworks serve to the space.

{% gallery ‘britomart’ %}

Hansen says, “Tracey has been a well known artist for a long time – I’ve personally admired her work for a long time – one of the things that struck me about it was the way she is making a political statement as well as creating something of beauty.

“She is re-editing media narratives that she sees as racist and transforming them into objects of beauty.”

The artworks are embellished with a vibrant colour palette inviting attention against the black urban fencing that it adorns. The colours, Tawhiao told The Britomart Foundation, are inspired by nature, particularly from the sea, where she lives and works in Piha. This shares a sense of freedom, both politically and artistically, to the urban onlooker. And possibly a reflection of the brief Hansen allowed.

Hansen says, “The artists are paid fairly, we are not trading exposure for art in that sense but it is a proper commission.

“Also, we are being as non-prescriptive as we can with the brief, so the only prescriptive part is that we have a certain amount of frames and the posters need to be a certain size. Apart from that, we are leaving it up to the artist to interpret how they want to work in that situation.”

It’s difficult to ignore the strong current of cultural diversity, and particularly the M?ori voice, seen vividly in the artists selected for the series. Certainly, this is visible in the selection of Tawhiao, but also in the artists to come such as Tyrone Ohia who, Hansen tells me, plans to reference the water of the Waitemat? before the reclamation for Britomart was undertaken, as well as the choice of artist and photographer Jermaine Dean, who is a current member of the FAFSWAG collective.

Hansen says the recognition for diversity came partly unconsciously, and partly from his experience as the curator of the New Zealand Festival of Architecture.

“One of the dominant narratives of the many events in the festival was indigenous urbanism, and talking about how unwelcoming many of our urban spaces feel to M?ori. They can’t see themselves in those spaces and to a certain degree, these spaces represent a colonial act that excludes M?ori.

“The selection of Tracey and a number of the other artists was about foregrounding M?ori narratives in this space and a response to some of the concerns and criticisms that were expressed at the festival of architecture and trying to embed those narratives into the city.

“Obviously, these are temporary projects so they don’t have a permanent effect, but I hope that by foregrounding M?ori artistic voices on a prominent site like this helps to engage people with that conversation. We see it as our opportunity to further these conversations.”

The significance of public art and, its subsequent voice to community spaces and the people within them, has long been a vehicle for cultural engagement. Earlier this year The Prime Minister and Minister for Arts, Culture and Heritage, Jacinda Ardern, voiced the need for openly accessible art: “The challenge … is that the benefits of art, and of culture are not always readily available to every New Zealander. They should be.”

A challenge relished by Hansen, who actively seeks every opportunity to bring public art into open public spaces.

Hansen says, “I have a wonderful urban canvas to work with here. There is a group that works on permanent artworks that works separately to me, and a level higher than me. My job is to bring art in a temporary basis into the area as much as possible.

“Because I have worked in arts and journalism for a long time I am conscious of the transformative power of art in public spaces, and how that can work in a complementary way with good architecture.”

Asked what the current landscape of public art in Auckland looks like, and if there is anyone in particular we should keep an eye on. Hansen says, “I would be loathed to highlight one or two out because I would miss so many out.”

“A lot of really good public art, especially Maori public art, is hiding in plain sight. If we spend a lot of time in urban spaces, we sort of forget to look with fresh eyes.”

Hansen points to the array of existing examples, from the Michael Parekowhai artwork ‘The Lighthouse’, to Chris Bailey’s sculpture Tauranga Waka – the resting place of canoes, and the Pipi Beds gifted to Britomart by artists from Ng?ti Wh?tua ?r?kei.

“It’s about supplementing permanent works with temporary works so that our streets can a lively exhibition space if we want them to be. So, it’s trying to look for the potential for art to liven public spaces with any opportunity we can get.”