Empathy, not imitation: Google Empathy Lab founder Danielle Krettek on why it’s time for businesses to match their EQ to their IQ

Krettek, a Nike and Apple design alumni, works across Google’s design group and machine intelligence group as the founder of its Empathy Lab. A lot of her team’s research directly affects how Google’s AI assistant Alexa is designed and interacts with its human customers.

In her words, Google is designing “products, not presences”. Speaking at Semi-Permanent Sydney, she said Alexa is meant to be like the family dog in the room along for the ride, supporting people’s most human moments.

“Don’t put eyes and ears on it, it’s weird,” she said of the tech industry’s tendency to go down the humanoid route.

“I think the far more interesting space is humanness. Which is what the essence of humanity? My secret fantasy is to be a Montessori teacher for these learning machines.

“The most human things are actually really hard for machines – what’s up, what’s down, what’s joy? What does it feel like to be messy? What does it feel like to have dreams and make mistakes?”

She referred to emotion as “the invisible language weaved into the work that we do” and says that a lot of people do it instinctually or subconsciously.

“In technology, we often think about ‘what are we doing? How does it work?’ What is interesting now is that it really matters how it feels. You have to think about stuff in a totally different way and bring more of your messy self to your design work, because you can’t access that space and have resonance with the person on the other side unless you’re going there yourself,” she said.

“We’re really at this point where it’s time for our EQ to match our IQ.”

She gave the example of a Harvard study that proved a machine needed to show vulnerability in order for a human interacting with it to show vulnerability.

Participants in the study came into a lab where a computer that had a terminal that would say ‘How are you? What’s your age? Where do you live? Oh and by the way, what’s something in your life you are most guilty of?’

People did two things, Krettek said: they lied and said they weren’t ashamed of anything, or they called the experiment ridiculous and left the lab.

In phase two, the study was redesigned so it wasn’t one side being vulnerable, it was a two-way affair. The computer was reprogrammed to read, ‘I’m a computer, I’m reading a script, I’m going to ask a few questions – let me tell something, I will crash. And it’s often at the most inopportune moments for reasons that are totally unknown to you, tell me about something in your life that you are most ashamed of?’

“And people were like ‘BLEEEHHH’,” Krettek said, imitating an outpouring of emotions to the amusement of the crowd. “It’s just in us, you can’t not do that. What’s fascinating is that sense of ‘Humans gonna human’, so when you’re designing for that paradigm, empathy is that thing that makes people more comfortable, but you also have to have a lot of integrity with it.”

See our Q&A with Krettek below. This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Listening to the way you work as Google’s Empathy Lab Founder and the paths you go down research-wise, it sounds like your job is a dream job: you get curious about something, and then you get to go fully in depth and research it. Is that how it works – you follow what sparks your interest?

I started the Empathy Lab three years ago, but I probably didn’t realise I started the Empathy Lab until a year and a half ago. I was like, ‘Wait, this is a thing that’s going well. I should probably call it something so it’s not just called Danielle’s stuff.’ Moments in your life can sneak up on you and I didn’t have a moment where I was like, ‘I founded the lab’. What actually happened was I was actually working on the most unsexy things ever – I was working on notifications and voice interaction. The thing I always did in my work was to look at the problem that needed to be inquired about. Take notifications: they’re so unsexy, we kind of hate them. It’s great if it’s a best friend, but mostly you’re like ‘Ugh. I don’t need to know that it’s six degrees colder tomorrow.’ So notifications are a really tough space for information.

So I went, I’m going to understand the anatomy of a notification, the nitty, gritty, crunchy details of people and how they feel about that. What I always do with a project is look at what is the creative angle: how can I make this interesting for people? Because I think the more creative it is, the more creative your designers can be liberated to be because you’re going to tap truth, you’re going to tap emotion and you’re going to tap a place in people where they’re like, ‘I didn’t think about it this way’.

So with the Airplane mode example (in an experiment, Google asked people to come up with other modes to set their phone in according to their mood besides Airplane mode. People came up with over 400 different modes, such as ‘professional mode’, ‘hungover mode’ and ‘gentle morning mode’. Krettek joked the latter two were essentially the same thing) people got to have fun with it and it gave so much truthful, authentic information about their lives. The piece you got out of it was about moods and rituals and how people emotionally travel through their days. The funny thing is the curious place isn’t always this field to pick flowers from. It’s not always as glamorous or interesting as the stories I tell at the end, but over time, I found that everyone was interested in the crazy, creative thing I did, so as I went through the last five-and-a half years, I started dialing more towards the creative, curious, interesting things. The lab is an exercise in courage and brave ideas and good questions and I built momentum over time saying, ‘This is the thing I’m studying.’

The more you own that – ‘This is the thing I’m studying, the design exploration I’m doing, trust me for a minute’ – and the more you follow that little voice while ignore the critic in your mind saying ‘That sounds batshit crazy’, the more you’ll get courage over time and then you end up a position like me where I look like I have a total dream job – and I do. I made it in the shape of me, I made it out of the work that gives me the most juice so I can give the most juice to the work.

When you think about people who work in the tech industry, the stereotypical person is someone that isn’t so personable – you’re so in tune with your emotions. So what first drew you to that industry, and how did you end up there?

The way I got into tech, I make the joke that I love Alice in Wonderland – Dad’s a surgeon, Mum’s an artist. Predictably, you can see my lineage in me and the need to make balance out of both. That’s so human and annoying. But I feel like my career is a backwards fall into the rabbit hole because I literally started in London working in a design and advertising firm where I was looking after the minority vote, or Rock the Vote for the UK, and the movements of social change for a greater good. Nike heard about that then I went to New York. I feel like all the places I’ve worked, I’ve been really blessed because of course they’re work, but they were an education. On Nike, I learnt what it was like to create feelings in people and bring them alive. I worked on Michael Jordan shoes and the idea that flight was possible. That got me noticed by Apple, so I worked by Apple’s ad agency, then I switched to the in-house design group. I was really blessed to be there for the golden years, when Mac made the switch to intel and Steve was like, ‘We’re going to tell stories about how Macs are not for creative people and coffee shops, it’s for everyday creativity, computers are a bicycle for the mind, this is about the human spirit’ and I was like Yes! Right?

Every good piece of work feels like liberation if you’re doing it right. I’d always been following feelings, then with Google I loved that it was so open: ‘We’re going to solve the most audacious, significant human problems with technology and we believe in everyone and that you should be open, democratic, free, even though we have products people pay for.’ The spirit of Google called to me because it was truly for everyone. I still don’t feel like I work in tech, even though I work on AI. For me to be at Google, I’m deep in the core of this technology and really proud to be there, but it’s all the more reason to bring the unexpected voices into technology – the storytellers, film makers and the designers – that’s the beating human heart of this.

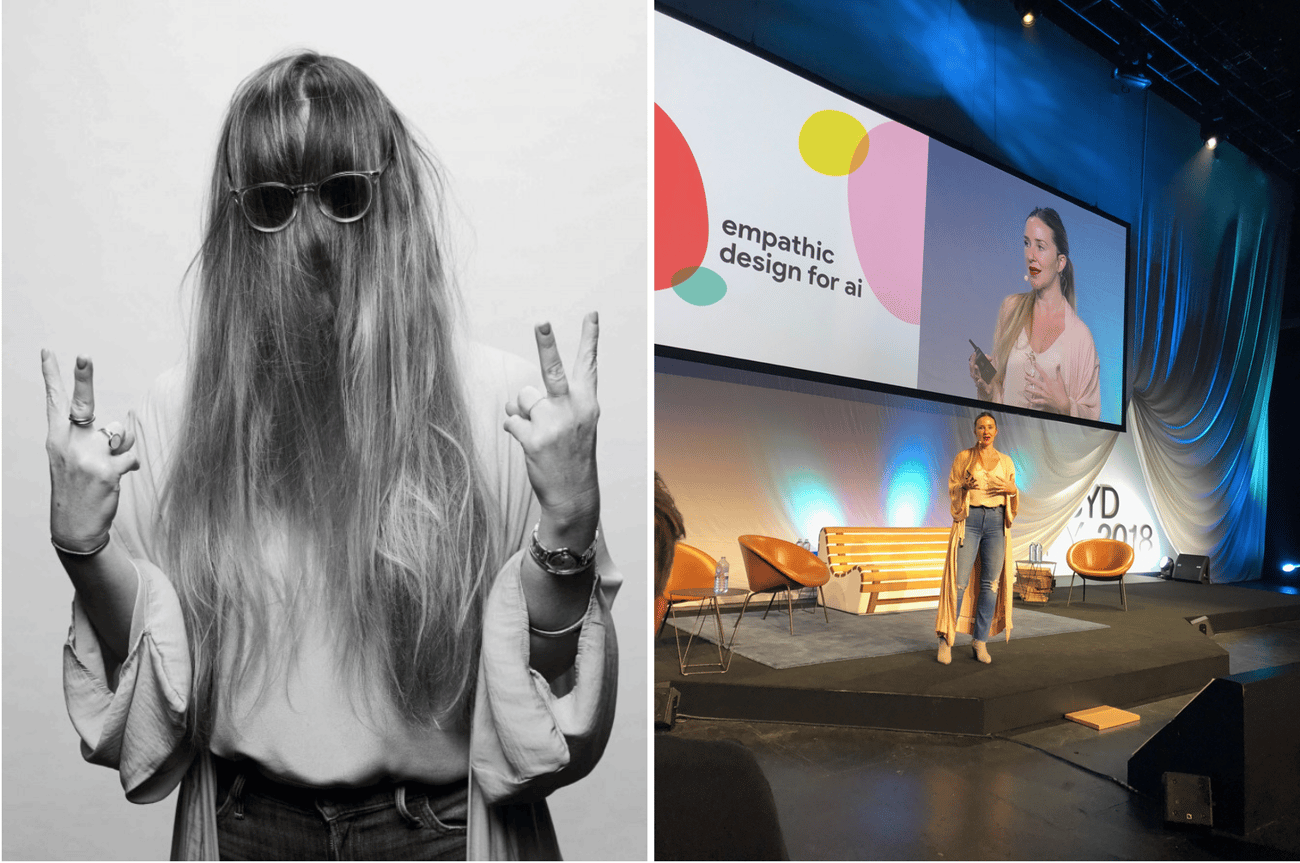

Danielle Krettek speaks at Semipermanent Sydney. Photo: Kristen Stephenson

I interviewed Jenny Arden (Airbnb’s user design experience manager) earlier this year and she talked about how companies like Airbnb will bring in an astronaut to be on the design team just because they want that completely new perspective to it, so it’s not just people in the tech sector.

It’s one of the things I study – I call them ‘the unexpected experts you need to listen to’. It’s like, I work with entomologists (the studiers of insects) as I’ll be looking at a product or problem and think, ‘What would be a very different way of looking at this?’ So if you look at gesture, you talk to dancers and choreographers, people that speak American sign language, and you pull from the full spectrum of non-verbal communication: neurobiology, physiology, art. It’s not just the designer and the art director, the table is so much bigger if you think with a genuinely human, inclusive lens, so I think that’s why Google’s always encouraged bigger, bigger, bigger, and I say I’m going to go deeper, deeper, deeper.

Why do you think there has been that humanity component missing from the tech sector and why is this changing now?

What’s so interesting about being in technology is humans are humans, to state the obvious, but the thing that is most challenging is actually at the culture level. People feel like they need to come up not just with problems, but with solutions. They don’t need to create messes, they need to clean things up. They need to be right, to be certain and to create and add value, and these are all things that make you a professional, adult human being that’s smart and successful.

What’s really challenging is the human experience is not that – we are not these decision-making engines, we are messy, emotional beings that are constantly traveling around, feeling all these feels and yet there’s a really weird thing that happens when you walk into work in the morning and you’re like, ‘I’m going to turn those things off because here is the place where I do the thing I’m good at and do it over and over again’. You’re shutting off however much of yourself that you don’t let that in the door. There isn’t a lot of space for not having an answer, so in that space where maths has an answer, science has an answer, it’s really hard to say, ‘Okay, the watery, messy parts of myself are just as important, because those are the unknown depths, but these are the great mysteries that move the human spirit.’ It’s hard to say, ‘I’m going to do the tough thing, I’m going to sit with the mess and trust that on the other side if I take more of me, the work will be better because more of me is in the work.’

Semipermanent Sydney

Not to pass judgment on men, but you do tend to find women are generally more attuned to their emotions, especially when you see people like yourself at the forefront of this shift in tech. Do you think having more women in leadership positions in business or in the technology industry is leading to this more humanised approach?

I think emotional intelligence is a skillset and it is ungendered. However, culturally there is more permission for women to be attuned in that way and more cultural training and practice around that, and it’s both a blessing and a curse. But looking at this as a skillset, everyone can develop these things, it’s not just the natural birthright of women. At the same time, I love the way women do hold this skill and this space wherever they’re operating, which is why I’m like, ‘More women everywhere, yes please.’ Gloria Steinem is one of my heroes, and I feel like by championing emotion in the tech space, this is still one of the frontiers of feminism and I’m really proud to raise my hand and be one of the many voices that are speaking for that.

Being emotionally fluent is not a soft skill. There are all of these ways of diminishing what it means to speak with truth and feeling and passion and power and I think being an emotional being is not a negative thing, it doesn’t exclude you from rationality, it’s actually a power like logic if you use it in the right way. I see women standing for that more and the more we can encourage it from both sides, the better. Men need to be allowed to have this aspect of feminine expression, it’s permission for everyone to feel and be felt and speak and be heard and take up the full space of themselves, which isn’t just about emotional intelligence, it’s about being a full human being. I think there are a lot of imbalances to be corrected.

We have been told the story that vulnerability is a point where we can be attacked, when actually, vulnerability, if wielded properly, is your greatest strength. My ability to stand up on stage and talk about how I sometimes feel like I don’t belong in these rooms, but I absolutely know I belong in these rooms, is a huge part of my power because if I can own that and say that, no one can write my story for me. There’s a lot of power in your vulnerability and your truth because you don’t feel like there’s anyone who will snipe at you for something, you’re whole and you’re expressed.

Semipermanent Sydney

Do you think we’ll ever reach a point where a machine will feel empathy?

I will never say never, because I don’t have a crystal ball. There are incredible advances being made, but in terms of being actually to being able to feel empathy, the definition I use by Brene Brown is the clearest: empathy is when the feeling that someone else is having and expressing is a feeling that you can recognise and be aware of in yourself. So much of emotional intelligence is the ability to recognise emotion in yourself, then recognise that in another, then be able to shift that or stay where you are based depending on how you want to be, so an empathetic moment requires that both beings are feeling beings.

What’s interesting about the space of AI is machines are able to do things humans can do, but I can’t see that far into the future where the machines would say ‘You’re feeling this, I’m picking up on that moment and have felt that in my experience as a machine’. That empathic leap I talked about – I do believe it’s possible because I already see it happening where we as humans are at the centre of the experience, meaning we have our abilities or emotions emphasised because of AI. The humanoid is the red herring. People say, ‘Lets make them just like humans.’ No, we should let them be machines, but think, ‘What more is possible for us?’ because we’re in this companion-like relationship where more is possible. That’s where it starts to get exciting.

To be fair to the incredibly talented folks doing this human-shaped work with AI, it’s not to say they shouldn’t be doing that. I think that in times of great progress, invention is about exploring all things. But I think I personally feel more connected to a future where the harmonious relationship with technology is defined by tapping my humanity and connecting with a machine that feels almost human in next-level intuitiveness, versus something that is trying to be like us, and never will be. Being humanoid is so much less powerful a space. It would be a great technological feat, but for me and the personal trajectory of my work and the work I’m doing with Google, connecting machines with the potential of humanity is just so much more powerful and so much more interesting.

There are people who believe it’s science fiction, as in it’s not now, but it could happen. I’m in it for the ride. If they need the first robot psychologist, I’ll be there.