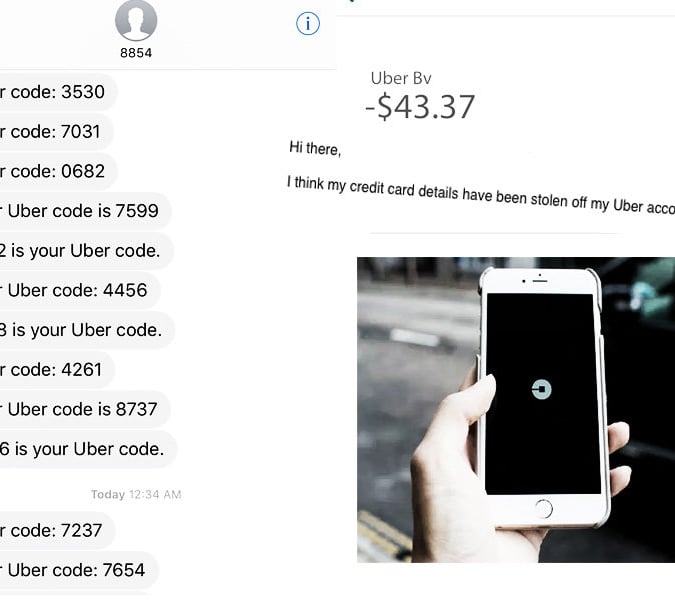

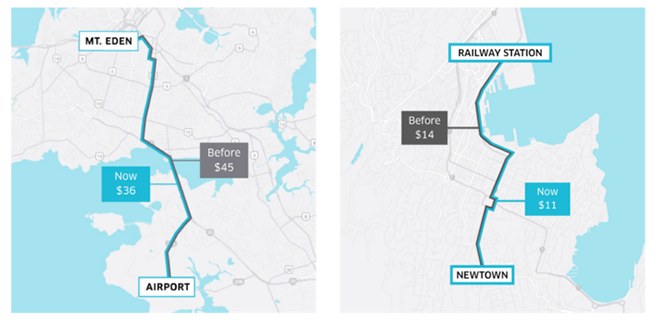

Yesterday, Uber announced via an email and social media that it would be reducing its rates by 20 percent and easing driver restrictions in New Zealand.

From the customer side, this news was obviously welcomed because it meant that riders would be getting a fifth of their journey price slashed.

However, the news wasn’t quite as pleasant for the drivers using the service.

Three drivers, who spoke StopPress under an agreement of anonymity, all expressed concerns about the shift in Uber’s policies.

They all said that in announcing the news, Uber didn’t consult drivers prior to sending out the group email to everyone using the service.

The drivers said that there were no efforts made by the company to inform them of the change prior to yesterday’s announcement, and that it was made unilaterally without consultation.

If an entire workforce lost 20 percent of its standard pay rate in other industry, there would be outrage. And while they don’t represent all Uber drivers, the three we spoke to all concurred that they were disappointed by the change.

One particularly incensed driver said that he would stop working for the service, adding that he felt lucky because he didn’t rely on Uber to survive.

Asked whether he thought other drivers should follow suit by also refusing to work for the company, he said that he didn’t want to speak for anyone else.

The second driver told us that in addition to dropping its rate, Uber had also updated its commission structure for new drivers.

“Uber used to take 20 percent from drivers who signed up before 20 April, but any new drivers after 20 April will have to pay 25 percent,” the driver said.

A third driver told us the 20 percent drop really does affect his pay and that he’d only just invested in a new car before hearing the news.

He said Uber had promised the drivers they would get more work because of the decreased fares, but he was sceptical.

StopPress has contacted Uber and is awaiting a response.

Uber’s policy shifts come at a time when the government has announced a raft of regulatory changes that will see both taxis and app-based providers included under the umbrella term ‘small passenger service’.

“Currently there are separate categories and rules for taxis, private hire, shuttles, and dial-a-driver services. In the future, these services will be regulated under the single category of a small passenger service,” the government statement says.

The government believes that these steps will help to level the playing field across the industry.

“This will allow all operators to compete on an even footing and to differentiate from competitors as part of their brand on aspects such as cost, service, environmental footprint and philosophy. Consumers will have a range of services to choose from, and can be confident that they can use these services safely. Drivers will also feel safe in their places of work.”

In the context of these new regulations, Uber’s decision to drop its prices certainly does look a competitive play aimed at keeping its riders loyal. How this pans out is yet to be seen, but the heightened competition should bring more good news for consumers.

This comes at a time when governments across the world are looking for ways to regulate Uber.

In the United States, legal proceedings earlier this year that saw the California Labour Board ruled that a former Uber driver was an employee and therefore eligible for unemployment benefits.

Upheld twice on appeal, this case was a major blow for the company.

As a Guardian reporter observed: “The case strikes at the heart of Uber’s business model, which relies on the firm positioning itself as a mere middleman between drivers and passengers. Many analysts have questioned whether the firm would even be sustainable if it was forced to provide standard employee benefits to all its contractors.”

Earlier today, news broke in Massachusetts that Uber had agreed to pay $100 million as part of settlement agreement, which arises from class action initiated by drivers with various claims.

But this does not necessarily mean that drivers’ woes are settled in the United States, or the rest of the world for that matter.

In an official statement released alongside the news of Uber’s settlement, attorney Shannon Liss-Riordan (who represented the drivers) said that the settlement has not resulted in legal clarity:

“Importantly, the case is being settled—not decided. No court has decided here whether Uber drivers are employees or independent contractors and that debate will not end here. This case, however, with this significant payment of money, and attention that has been drawn to this issue, stands as a stern warning to companies who play fast and loose with classifying their workforce as independent contractors, who do not receive the benefits of the wage laws and other employee protections. As a result of this litigation, many companies have chosen to go the other way and not fight this battle, and instead to classify their workers as employees with all the protections that accompany that classification.”

At the moment, these issues might be restricted to the Uber drivers but this is changing quickly.

The gig economy is already flourishing in advertising, with companies like Fiverr offering creative services at a fraction of the cost of what they are available for in the general market. If you have a clear brief and know exactly what you want, you won’t have much difficulty picking up the services you need from a freelancer somewhere in the world.

Of course, Fiverr doesn’t have the scale or clout of Uber yet. But with more than 200 people in five international offices and a recent prop-up of US$60 million in investor funding, the company is growing quickly.

It wasn’t long ago that musicians were the only ones on the hunt for gigs. However, with the growth in companies serving as middlemen between driver and rider, buyer and seller, or business and freelancer, a growing proportion of our workforce could potentially find themselves on the hunt for the next project.

While this is creating a host of very exciting and innovative companies and giving some workers the freedom to work when they please, it is also rather quickly unravelling the notion of job—or pay—security. And the jury’s still out as to whether governments can keep up with how quickly this is all changing.