Since 1990 there have been 3,900 fewer sheep in New Zealand every day. And, in the 1950s, when the New Zealand economy was booming, there was strong demand for wool and meat and New Zealand became accustomed to solid returns. That was exactly the time companies needed to force themselves to be paranoid, and to imagine what disruption might come to their markets. Instead of innovating, the New Zealand sheep sector settled in. And what hit the sector was the market dominance of synthetic textiles. At first, those textiles didn’t look like a threat, they looked like inferior fibres. In no time, the New Zealand wool industry was in trouble.

Ten years ago, taxi companies had their challenges: deregulation, the cost of petrol, cheaper travel and the increased use of public transport. The taxi companies acted the way all big businesses act and just did more of the same. No-one saw a whole new business model that would turn the taxi industry on its head and force it to fight for its very survival. Yet that’s what Uber has done. Using ordinary drivers in their own cars, Uber has cut prices, changed consumer expectations and challenged the taxi industry at a fundamental level.

That’s the thing about disruption. It was an opportunity long before it was a threat, but it has taken the entry of Uber into the marketplace for other taxi companies to develop apps and bring their offerings into the digital age. And it took the destruction of much of the New Zealand wool industry for it to turn itself inside out.

Disruption will come to every sector. When it does, companies must have the flexibility to create commercial models that allow it to happen, and commercialise it. For most companies, it’s not a lack of good ideas that’s the problem. It’s a lack of appropriate commercial models that allow the company to bring new products to market.

When disruption first appears, it often seems comical and hard for the incumbents to take seriously. But innovations that didn’t seem as though they could be a serious threat have the power to change the status quo beyond recognition. Usually, too, the new thing is not as good as the existing one at first, so it’s hard for companies to imagine how it might develop and displace the status-quo.

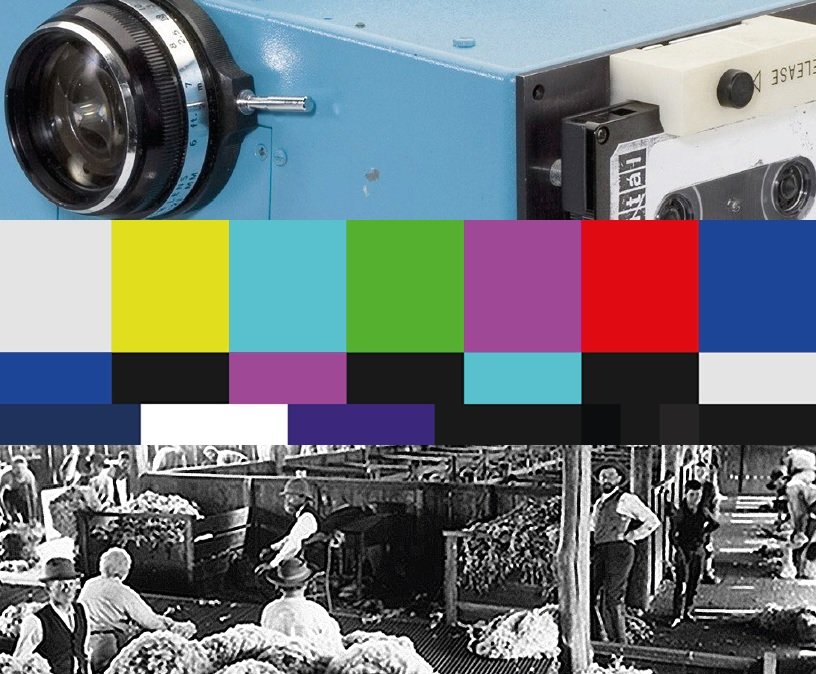

History is littered with famous examples of people who didn’t recognise disruption when it was staring them in the face. The inventor of modern electronics, Lee de Forest, said that television was commercially and financially impossible. Kodak invented the digital camera, but because it wasn’t initially as good as their high-end SLR camera, they dismissed it. In New Zealand, the wool carpet industry was disrupted by synthetics. They didn’t see it coming. Why would people not want the best wool on their floors? Because for many customers, other factors – price, durability, convenience, the ease of cleaning, and the ability to replace flooring more often – came into play.

In the agricultural sector, we need to think about the future of food. But the future’s already here. Silicon Valley company Impossible Foods has invented a plant-protein burger that looks, tastes, and cooks like red meat. Its founder and CEO, Patrick Brown, sees the market as meat eaters, not those already attracted to quinoa and beans. He knows that the world simply can’t satisfy its growing appetite for meat by using animals. The burger his company has developed uses fewer resources, is healthier and will eventually be cheaper than red meat. It apparently tastes great too. Beyond Meat, based in Los Angeles, has also produced an acclaimed pea-protein burger. Bill Gates is backing both companies, as is Google Ventures. Plant-based meat has huge implications for New Zealand agri-business.

But our companies can’t disrupt themselves, no matter how hard they try. Why? Because the culture, resources and profit formula of an organisation are intertwined. The model is about adding value, not creating it.

In New Zealand, Spark has tried to disrupt itself. It has managed to sustain innovation, through its offshoots Bigpipe and Skinny mobile, rebranded existing products, with a tweaked business model. But Spark’s foray into on-demand streaming through Lightbox has been less successful. Despite offering free sign-ups, its user base is low and, although its figures aren’t public, is probably not a commercial success. Spark’s move into home security through Morepork is also unlikely to succeed. Both require different cultures, resources, skills and profit models, and that’s usually incompatible with core business. So the formula of the core business conspires to kill off the new enterprise.

The only way incumbents like Spark can disrupt themselves is to create a separate business unit for that purpose. They have to spin it right out of the core business, give the unit its own identity, and then leave it alone. But that’s too hard for most listed companies to do, when they have to do continuous reporting and keep their share price up.

The reality is, creating whole new products and markets with a different profit formula is almost impossible inside a larger company – no matter how smart its people are. Big enterprise resource planning (ERP) software companies struggled to move to the cloud and a software-as-a-service (SaaS) model because their profit models, and sales remuneration systems, were all set up around multimillion dollar sales, not monthly rentals. This is why it was the newcomers – AWS, Google, etc. – who have won in the hosting space and not IBM (although it bought in later).

Similarly, Fonterra’s ‘volume, value and velocity’ story is hard to execute. Volume businesses have one set of profit/culture/resource models while companies that create (not add) value have to be completely different. This tension plays out in Fonterra, where it is good for the value-add part of the business if the milk price is as low as possible, but not the farmer-owners.

What large companies can do, though, is continuous sustaining innovations. They can continuously improve on their core products – and have to in order to keep their most demanding customers happy. Protecting your patch through regulation or legal challenges to the upstarts disrupting your business won’t work.

The wool industry has been turned inside out – all the business models have changed. They took a market-shaping approach (from volume to value), new business models and undertook heavy investment in market innovation. This was supported by funding from the Ministry of Primary Industry’s PGP Fund and growers themselves paid up through a non-compulsory levy. This led to the creation of new disruptive market categories. Icebreaker is famous for creating the active outdoors catagory. Wool shoes such as Glerups and Allbirds didn’t exist a couple of years ago.

John Brackenridge from NZ Merino sums it up: “New Zealand must be prepared to disrupt and shift away from anachronistic models. To do so requires a fundamental shift within business and across industries. The rewards for New Zealand in getting this right are huge, failure to do so is likely to be harmful for New Zealand socially, environmentally and economically”.

New Zealand producers are at a fork in the road. Do we use the technology we have to increase the volume of food we produce? Or, do we use our technology to produce the world’s best, cleanest, most ethical and delicious food?

We can’t choose both. Will we be the disrupted, or the disruptors?