You can hardly move these days for new thinking on the potential for digital technology to remake the world we live in within a generation.

A world in which every machine is wired to every other, foreseeing our wants and needs, and meeting them seamlessly. Where medical technologies will be able to be controlled by neurological commands and where the blue and white collar jobs of today are likely to disappear in droves.

Previous waves of technological change have always ended up producing more and new jobs than those that were lost by the change. The cause for optimism about the future of work, based on past experience, is strong. But that optimism is cold comfort for the 46 percent of the workforce that studies suggest are at high risk of being replaced thanks to automation and robotics in the next 20 years.

The reality is that the new jobs are likely to require di erent skills, may not be as well-paid in many cases, and won’t necessarily be in the same places as the jobs are now.

There’s a lot of airy talk of new jobs requiring ‘soft skills’ – the ability to deal with others. For many, that is code for looking after the wave

of elderly people who are steaming over the horizon and will require the kind of care that

robots simply can’t give. A robot can maybe dispense some pills, but a robot that bathes and cleans you is, if you ask me, likely to meet a bit of customer resistance.

A study by CA, an Australasian accounting body, and the New Zealand Institute of Economic Research warns that regional economies are in particular danger of an accelerated hollowing

out as these trends develop. Auckland and Wellington stick out as the places where the least jobs are at risk from technology.

And given the speed with which this change is coming upon us, it’s reasonable to ask whether that most cumbersome of things – a central government – will prove su ciently agile to create the best possible environment in which to embrace the good and manage the bad.

But, these issues are emerging on the political agenda. In a year’s time, expect them to be at the centre of the political debate ahead of the 2017 election campaign.

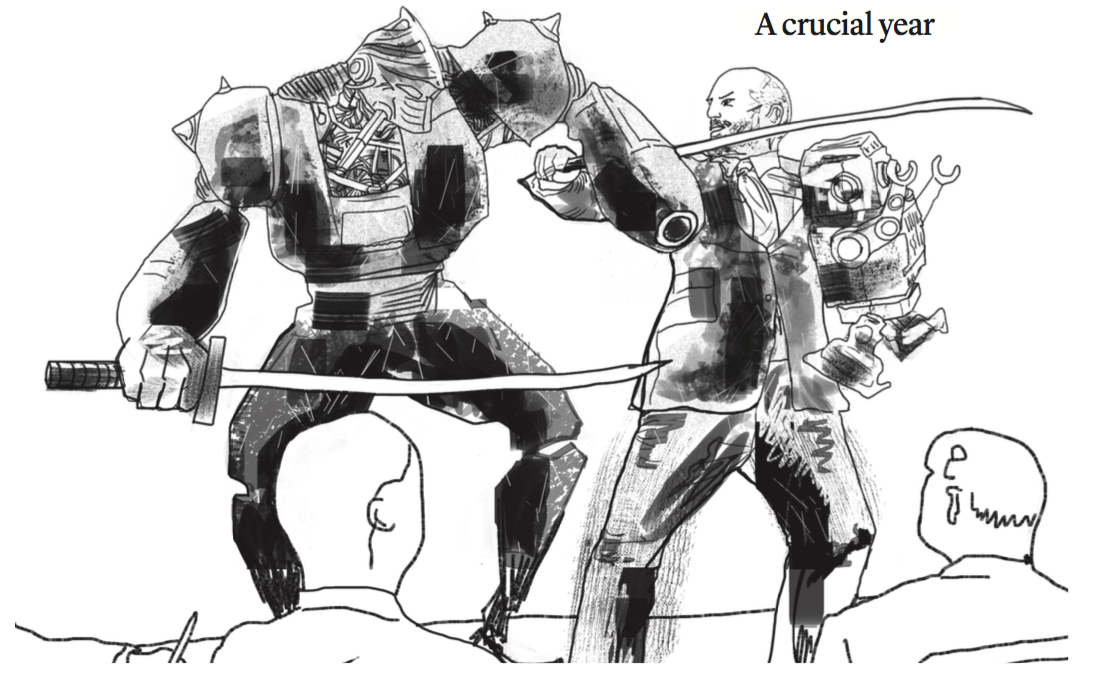

That makes this year a crucial year politically, especially for the Labour Party, which has spent the time since its 2014 defeat quietly repairing its internal relationships, deciding it can live with the sometimes somnolent and tin-eared Andrew Little as its leader, and dumping old policies that were vote-killers.

Into the resulting vacuum, Labour must now start pouring policy. If it doesn’t do that by the end of this year in a solid and convincing way, then only a collective migraine at the thought of a fourth term led by John Key will get Labour and its allies over the line to form a new government.

Of course, it’s also conventional political wisdom that opposition parties don’t win elections, governments lose them. In theory, Labour

could continue to wallow in its current soup of undi erentiated policy and hope for the best.

But that’s not the plan. Rather, nance spokesman Grant Robertson must use this year to put esh on the bones of his Future of Work Commission – a worthy exercise that has yet

to light any res, but is at the heart of Labour’s need for new positioning. He’ll be hoping his conference in March, addressed by one of

the global gurus in this area – former Clinton administration labour secretary Robert Reich – will be agenda-setting.

If he u s it, Labour may have all kinds of policies about all sorts of things, but it won’t

have a de ning platform. In fact, if Labour’s

not careful, National will try to out ank the discussion of the future of work, stealing ground from the centre-left in the same way as the 2015 Budget’s bene t increases – which will kick in this May – undercut Labour’s mortgage on caring.

The evidence of some such manoeuvring

can already be seen in the inquiry into tertiary education provision that Bill English and Steven Joyce have ordered up from the Productivity Commission.

Not only are ministers not sure what they’re getting for their money from the tertiary education sector, but they worry it’s not able to adapt fast enough to the changing demand for higher education that a very fast-moving labour market might demand.

If it’s true that as many as half of all jobs are at high risk of being automated in the next 20 years, then policies to anticipate such a huge impulse are urgently needed.