We recently interviewed Sennep’s co-founder Hege Aaby ahead of Semi Permanent, and at the event in Auckland last week she and co-founder Matt Rice showed off some projects that prove it can be more important to engage the user’s heart than their head.

When you’re talking to a room of designers and creatives, you need edgy labels for your trade secrets. Aaby and Rice’s are ‘seeds’ – little R&D explorations and motion prototypes that can turn into big things – and ‘passion projects’ – work that throws off the shackles of client demand.

Playful experimentation gives Sennep’s work a sense of personality and evokes emotion in their audience, says Aaby, something she says is more important – and less common – as the digital world zeroes in on process, numbers and analytics.

“Passion projects are crucial in the development of our company. The excitement and the energy you put into creating something can be felt by the person that sees it.

“We believe play is the best form of research and over the years we’ve really seen the value of learning by doing.”

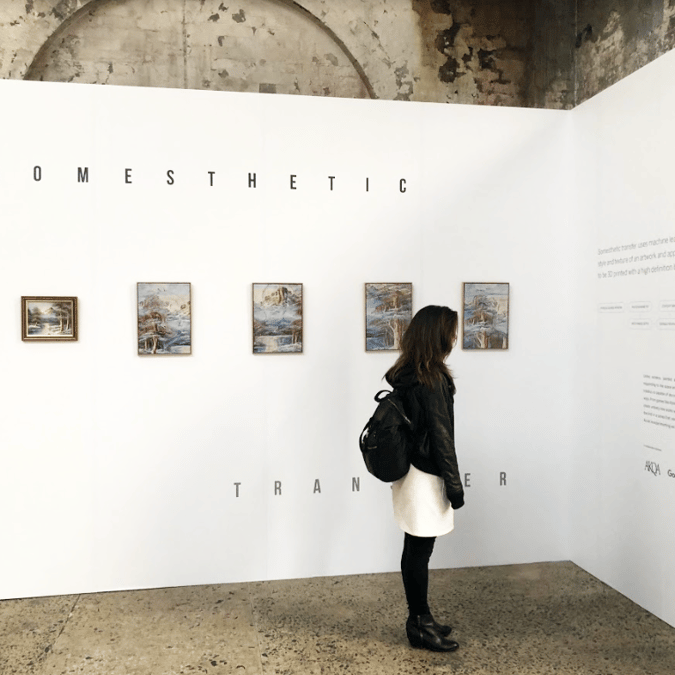

Image: Sennep co-founder Hege Aaby

Sennep’s most blossomed ‘seed’ is the iOS multi-player game OLO. Strikingly simple, as many of the most addictive touchscreen games are, players send a virtual disc into a scoring zone to get a point, losing their disc to their opponent if they shoot it too far.

Within two weeks of its release as a web app the game had about 50,000 players and on arrival in the Apple store it won Editor’s Choice worldwide, becoming the number one game in 22 countries. Within weeks of that launch they’d made their money back and it became their most profitable project.

But the global hit began as a ‘seed’ when one Sennep developer had enough downtime to test how HTML5 could be used to make coloured balls move around smoothly.

“It was a pure passion project with no design compromises,” says Rice. “There’s real value in taking these experiments further. Apple called OLO a multiplayer masterpiece. That was good validation of sticking to your design principles and believing in your own ideas.”

Another ‘passion project’ was born from one Sennep staffer’s frustration over long waits for the bus. And when Transport for London released its live traffic data, the agency seized on a solution with the Bus O’Clock app. It overlaid the data with an analogue clock interface to tell bus users when their ride would turn up at their stop within the half hour.

The clock interface is one of many nostalgic devices the agency’s used to win their audience’s hearts. Instead of cluttering OLO’s minimal board, they tucked the menu behind it in the way that chess pieces are stored within a foldable set. And as the OLO board opens it becomes a music box with tunes that speed and slow under user control.

The art piece Dandelion – part of the Victoria and Albert Museum’s Decode exhibition of digital design – was also a nod to Aaby and Rice’s past. Each ‘80s kids, they loved blowing seeds off dandelions, so they used 3D gaming software to create an interactive work with a hairdryer as the controller.

“People just knew instantly what to do,” says Aaby. “Behind the scenes it’s full of technology but as interactive designers we want to hide this technology so people only focus on the interactive experience.”

Aaby and Rice say they’re now winning client work based on trust in their approach, and a key part of this is making complex information simple.

Their job with LSO Play was to help find a new audience for classical music and educate children about the sections of an orchestra. Visitors to the site can zoom in on four HD streams as the musicians perform Ravel’s Bolero, and interact with a diagram of the orchestral layout.

Today users are familiar with digital navigation on desktop and mobile, but Sennep’s early use of experimentation and play was based on real world objects that drew out user emotion.

Their 2005 creation for retail design agency Checkland Kindleysides used papercraft to show how ideas could come from a blank sheet of paper.

“We worked on and off the computer, cutting paper shapes by hand to understand how they would fold and then work on the computer to try to realise this,” says Aaby. “We were fascinated by how the human brain works. You make up your mind in a split second whether you like something or not and we tried to engage people’s hearts before their rational brain kicked in.”