If you take a look at the statistics, it’s pretty bleak. From secondary education to higher study, occupation to new ventures, in New Zealand, women are underrepresented across the board.

While primary education statistics show equal gender participation in the sciences, a gap appears in high school and continues to widen through higher education, reaching its most extreme at PhD level (especially for engineering, where women make up just 15% of the engineering PhDs).

(Source: http://www.awis.org.nz/wis-in-nz/statistics/)

And while female students are over-represented at university, subject choices continue to reflect an aversion to IT and engineering: In 2011, just 20 percent of students completing a Bachelor of Science in Information Technology were women.

This pattern is repeated moving into the workforce, with women underrepresented in STEM-dependant workplaces.

According to the last census, of almost 40,000 computing professionals, only 25% are women; of 6,132 IT Managers, only 22% are women; and of 6,291 computer equipment controllers, only 25% are women (source).

The disparity then continues across average income for BSc graduates.

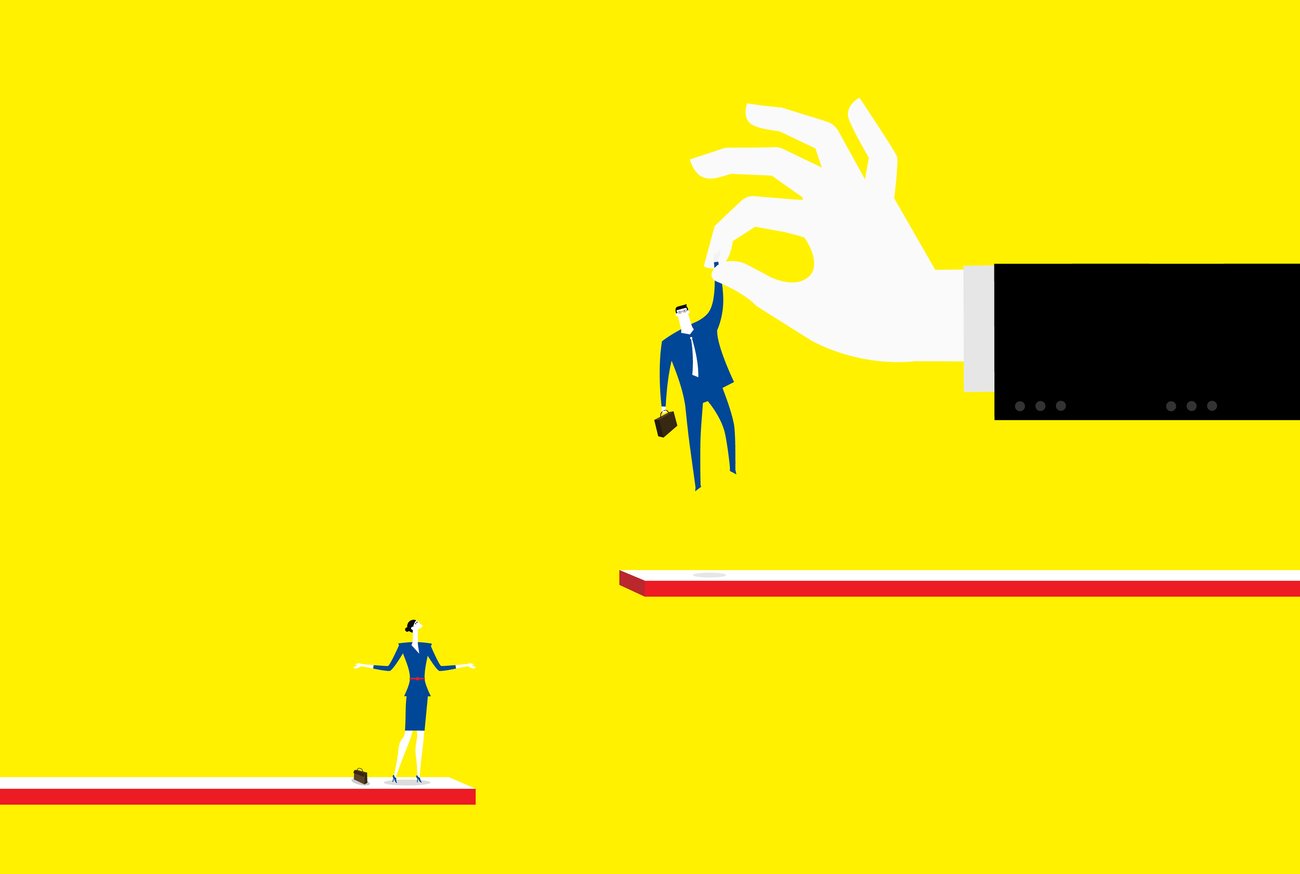

So while the gender pay gap is closing, it still sits at 9.9% in median hourly earnings between the sexes, attributed in part to occupational segregation and ‘unconscious bias’.

In a nutshell, there is a huge gender representation gap in the study choices, status and pay of those working in the science and IT fields.

So the question is this: There are plenty of good reasons to close the gap, so why don’t we?

The culture

Worldwide, women are under-represented in innovation, with female inventors taking out less than 1% of all patents, with a similar ratio likely here.

“In New Zealand 15% of angel and VC money goes to companies that have a woman founder,” says Melissa Clark-Reynolds, technology entrepreneur and founder of Seven Dragons.”

“In the US it is 0.97%.”

That may be heartening from a global perspective, but being more socially progressive than the US is rarely considered an achievement here.

Sue Ironside, chair of Baldwins Intellectual Property, says the disparity is systemic and begins at school.

“I look back at myself at school,” she says. “I did sewing and cooking, and at that time, you just didn’t get a chance to woodwork and metal work. I ended up in the IP space, but that was just me. There are very few women in my age bracket out there doing innovative, creative stuff.”

Image: Sue Ironside, chair of Baldwins Intellectual Property

A workforce not optimised for women

“I believe there is some hidden bias in the workforce,” says Victoria Crone, managing director Xero.

“We’ve been conditioned for so long that this is what the workforce looks like and this is what an executive looks like. We aren’t seen in the same way that men are sometimes seen.”

Crone says that the fact that primary caregiver responsibilities are rarely taken into consideration in the modern work environment disadvantages women attempting to perform in both work and care roles simultaneously.

“Juggling really large roles and being a primary care giver is very demanding and it takes its toll,” she says. “The work environment is just more suited to men. It’s hard to manage the things I have to be at along with my family life. It’s hard and women may just end up saying ‘that’s too hard’.”

Image: Victoria Crone, managing director Xero.

Crone says that in innovation and technology spaces, women have very low re-entry rates after having children.

“The workforce isn’t optimised for [family-oriented leave] so we often don’t want to go back into it. Technology is so fast moving that it’s hard to take a lot of time out. When you come back in, there’s often not a lot of support to manage that.”

“Look at it this way: there are few breastfeeding rooms in the workplace for new mothers. How are you going to support that? It’s been that way for 100 years, so it’s not really a surprise, but it’s not ideal either.”

So is it a case of the workplace still being an ‘old boys’ club’, where women, regardless of their performance, are still considered outsiders?

“That probably is a part of it, to tell the truth,” says Ironside.

“I’ve never had an issue in my career but I know it’s prevalent out there. I think I was lucky with my bosses. They were very progressive. I have been paid the same as my male colleagues, I’ve had the same opportunities, but I may have just been lucky.”

So what’s being done to address the imbalance?

That’s the good news. Just as the gender pay gap is rapidly closing in this country, attitudes are changing too, new ideas are being promoted and work is being done to maximise women’s involvement and contribution in the science and technology industries.

That starts with schooling, says Bryn Lewis, devMobile developer and one of the founders of CodeClub, a nationwide network of coding clubs for kiwi kids aged 8 to 12, which provides girl-only environments for would-be coders.

“IT is a great business,” says Lewis. “It’s gender-friendly, doesn’t require physical strength, it’s well-paid and family friendly, so it’s a shame that more women aren’t involved. It’s sad that in the IT industry 50% of our intellectual capital is disenfranchised,” he says.

To that end Lewis created the CodeClub, a volunteer-based primary and intermediate after-school program that aims to teach young people to program via computer game, animation, and website-oriented challenges.

“I’ve got an 11 year old daughter and I wanted to give her the opportunity to choose IT as a career,” he says. “We need to get girls thinking about IT early on, and girls-only clubs seem to create an environment where they can learn. They haven’t necessarily decided to become programmers, but they’ve decided to embrace IT as a career.”

That however, brings its own problems, says Lewis.

“Unfortunately, we struggle to get female volunteers. There aren’t many women in IT to start with, and we have to be careful not to burn out the ones we’ve got.”

“I would just like there to be more women in the industry, because that makes the teams that develop the software more representative of the communities that consume it.”

Crone concurs.

“There are three levels that need to be managed,” she says. “Firstly, we need to encourage kids into these careers, showing them how fun and challenging and demanding they can be, and showing them that it is just as good as any other profession. Then we need to make sure that we’re making that tech fun and accessible, and then we have to increase the number of kids getting into those STEM subjects at university.”

When that interest is sparked, it’s just a case of creating systems that can nurture support that decision, post-higher education, says Crone.

“It’s about supporting women as they leave university and enter the workforce,” she says.

“Going from university where you’re a minority in these subjects, women are finding that they’re an even greater minority in the workforce. We’re only beginning to set up those support networks now.”

“It’s about making sure you’re not putting obstacles in the way, either consciously, or unconsciously. At the senior level there needs to be mentors and champions that will encourage and push women into those roles. We [women] tend to be a little more conservative around the risks we will take, so that support is important. And it’s not just in terms of women, it’s also culture and age. We need greater diversity and more young people in our enterprises and on our boards.”

Positive effects

As attitudes change, and as female innovation leaders emerge, they are serving as role models, encouraging others to follow in their footsteps.

“There are female innovators in the space, but they are perhaps a little more unassuming in the way they conduct themselves,” says Ironside, “but even that’s changing”.

“There’s a little bit more confidence for women to be out there as innovators, and they’re starting to encourage other women. There are more and more coming through, like Michelle Dickinson who is fantastic, and they’re encouraging other young innovators. It’s all about encouraging women into that space.”

Mary Quin, CEO of Callaghan Innovation says that we’re at something of a tipping point for women making their mark in New Zealand innovation.

“There are still cultural factors at play,” she says, “but they’re diminishing and they have diminished substantially. I see huge potential there and it’s essential that we tap into that half of the population to contribute to these high growth and manufacturing firms.”

“Overseas, women are creating more new businesses than men. Women are starting up companies, but are less likely to take on equity capital to grow those companies to make them bigger. So there may just be a different risk profile that women have that makes them more cautious of the risks of bringing in outside investors.”

“But New Zealand now has a critical mass of women who are running companies and women in science who are very visible in their work – you don’t have to search hard to find women in innovation and entrepreneurial roles. Those role models are there so the next generation are not going to see [women in leadership positions] as unusual. That makes me feel very optimistic and encouraged.”

Image: Mary Quin, CEO of Callaghan Innovation

—

Resources for young innovators

Code Club Aotearoa

Code Club is a nationwide network of free volunteer-led after-school coding clubs aimed at children aged 9-12.

Mind Lab

The Mind Lab by Unitec aims to enhance digital literacy capability and the implement contemporary practice in the teaching profession. They offer a range of services, from school holiday activities for children aged 7 to 12 years to post graduate scholarships for public school teachers.

Refactor

Formerly operating under the Girl Geek banner, Refactor runs events to encourage, support and motivate women working in, or passionate about, technology.

Girl Code

Girl Code offers young women a chance to experience real tech projects before going to university. No coding experience is necessary and it is open to ages 15 to 19.

Gather Workshops

Gather Workshops support students and teachers looking to learn programming. Their manifesto states they’re looking to break stereotypes about what type of people become creative IT professionals.

OMG Tech!

Founded by Vaughan Rowsell, Michelle Dickinson and Rab Heath, OMG Tech! runs events designed to promote science to young people, including “robots, nano, biotech, rockets, programming, and mind control”.