Innovating by the seat of their pants: The million-dollar Kiwi helicopter sim made out of Japanese tsunami scrap

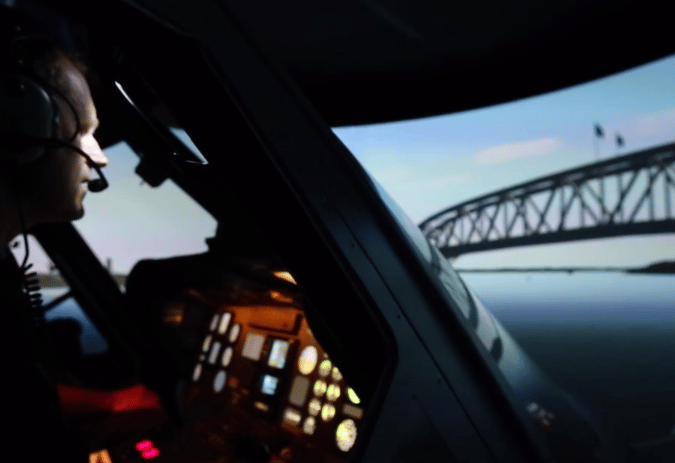

The sea beneath the Auckland Harbour Bridge has always seemed a long way down when I’ve looked at it at road level. From below, for some reason, the span looks ridiculously close to the water. The gap between the uprights seems to have shrunk too.

Maybe the tide is especially high today. More likely it’s because I’m heading towards the bridge 50 feet off the water at 200km per hour in a multi-million dollar Sikorsky S-76 twin-turbine helicopter.

The S-76 is a beast. One of the sleekest-looking large helicopters ever built, it will make almost 280km/h flat out and fly its passengers or cargo 750km on a tank of gas, then land them on anything the size of a tennis court. Right now, at 200km/h or so, it flies more or less like the fixed wing planes I’m used to.

It’s keeping me busy though, and my eyes flick from the radar altimeter to the approaching span as my feet keep us in balance and my left hand tells the 13m main rotor how hard to pull us through the air.

Then, just as the shadow of the bridge flashes over the cockpit, something strange appears in my peripheral vision. It’s photographer Adrian Malloch, flying 50 feet above the expansive Waitemata Harbour, in perfect formation alongside my helicopter.

He’s not flying, of course – and neither am I.

Rather, Malloch is standing next to the front end of a real Sikorsky S-76, recovered from the aftermath of Japan’s 2011 tsunami and turned into an eye-wateringly authentic flight simulator by the Northland Emergency Services Trust (NEST), based at Whangarei Airport.

The airport is a bit sad; a closed-down aero club, the odd Air NZ flight arriving and departing, and a bit of parachuting on nice days struggle to make its rather lovely 1000m runway look anything other than empty.

But the story of how NEST created a simulator in one of its hangars is almost as awe-inspiring as my pretend ride under the bridge.

It started with problems the trust was having getting spare parts for its three S-76 helicopters. The organization had chosen the S-76 model for its long range, speed, carrying capacity and ability to operate in bad weather –important attributes for an operation aimed at saving lives all over the upper North Island.

Commercial S-76 simulators cost around a million dollars, which is money the trust would rather spend on rescuing people. So they decided to make one themselves.

The only drawback was no one else in New Zealand had them. So it made sense for the trust to set up its own maintenance facility and build up a stock of spare parts.

Which is where the 2011 Japanese tsunami came in. A S-76, irrevocably damaged after being submerged in water, came up for sale. The trust bought it for $US40,000, planning to salvage as many usable parts as it could.

They did, taking what they needed and selling some surplus parts to overseas operators, more than covering the $US40,000 cost.

It was about then that the idea was hatched for a simulator.

“Instrument flying – flying in cloud or bad weather – is an important capability for us, but it takes a lot of training to get new pilots qualified and keep qualified pilots current,” says NEST chief pilot Peter Turnbull. “Having a simulator would save on training costs, and allow our pilots to do more training in less time.”

Commercial S-76 simulators, unfortunately, started at around a million dollars, which is money the community-funded trust would rather spend on rescuing people. So they decided to make one themselves.

As luck would have it, one of the trust’s co-pilots was a bit of a simulator whizz. Former IT guy John Keller had built two smaller helicopter simulators in the past, so leapt at the opportunity to turn a real S-76 into the ultimate training device.

It took Keller and the NEST team two years and $150,000 to complete the project. (Although, as he points out lying under the helicopter’s nose tinkering with something, it might never really be finished.)

Apart from the real helicopter body – everything from the nose back to the rear of the passenger cabin – everything is either locally made or bought off-the-shelf.

For example, the scenery outside the helicopter – including the Auckland Harbour bridge and all the airports NEST uses – is projected onto a 180-degree screen planned and built by an Auckland skateboard ramp builder.

The simulator received Civil Aviation Authority certification in 2014, and has been busy training the trust’s pilots and crew members ever since.

The next step is to equip the cabin with the same medical gear carried by the trust’s real S-76s, Turnbull says, including a patient mannequin for the team to practice on.

The one thing the simulator doesn’t offer is motion – which means it is officially known as a “flight training device”, rather than a simulator, he says.

Instead, the fuselage sits still on the floor as the projected visuals move around it, although the pilot seats do come with home theatre “seat shakers” that give a good impression of actual engine vibration.

However, the surround visuals are so convincing that you don’t miss the movement – and more than one passenger has been so convinced they’ve felt airsick, Turnbull says.

A Japanese S-76, irrevocably damaged in the 2011 tsunami, came up for sale.

The trust bought it for $US40,000, planning to salvage as many usable parts as it could.

And it’s not just NEST pilots who get to fly the simulator. The trust rents it to corporate groups and individuals for joyrides, raising funds ($200 for an hour) and community awareness at the same time.

While the team has created what is undeniably an awesome toy, the real payoff isn’t in the grins of the people who get to fly it for fun, Turnbull says. It’s in the looks they get from the patients they pick up in the middle of a shitty, stormy night, in the middle of nowhere, thanks to the piloting skills they perfected on solid ground, in a hangar full of computer parts, a salvaged helicopter and a million dollar’s worth of Kiwi ingenuity. ?

How it works

?Cockpit

The simulator is built into a real Sikorsky S-76 forward fuselage so the flight controls (stick, pedals and collective lever for rotor control) are 100% authentic.

The instrument panel is an exact replica of NEST’s three helicopters, but the mechanical gauges are replaced by small digital screens. A computer in the rear cockpit allows an instructor to set weather and introduce systems failures during training.

SoftwarE

The simulator is powered by X Plane – a commercial open-source flight simulator that fans claim offers more authentic aerodynamics than alternatives such as Microsoft Flight Simulator.

Scenery

While most of NEST’s training happens in cloud or at night, X Plane offers fairly detailed New Zealand scenery, including the Auckland Harbour Bridge and all the airports the trust flies to. The landscapes are projected onto a curved 180-degree screen designed and built by an Auckland-based skateboard ramp builder. Paris and New York are popular options for joyrides too.

Visuals

Five standard data projectors combine to create a seamless image that covers the pilots’ and rear passengers’ complete field of vision.

Computers

The simulator runs on six high-end gaming computers.

Facility

The simulator is housed in a light-proof room built by NEST staff inside a hangar at Whangarei Airport.