There’s been more media attention on the issue than ever before, but the fact remains that there’s still a significant gap between the number of young women and young men going into STEM careers. Research conducted by the Boston Consulting Group shows just 35 percent of girls graduating from high school go into science as a career, with only 18 per cent graduating. Things are a bit better in Aotearoa, with about 40 percent of science bachelor’s degree graduates being female.

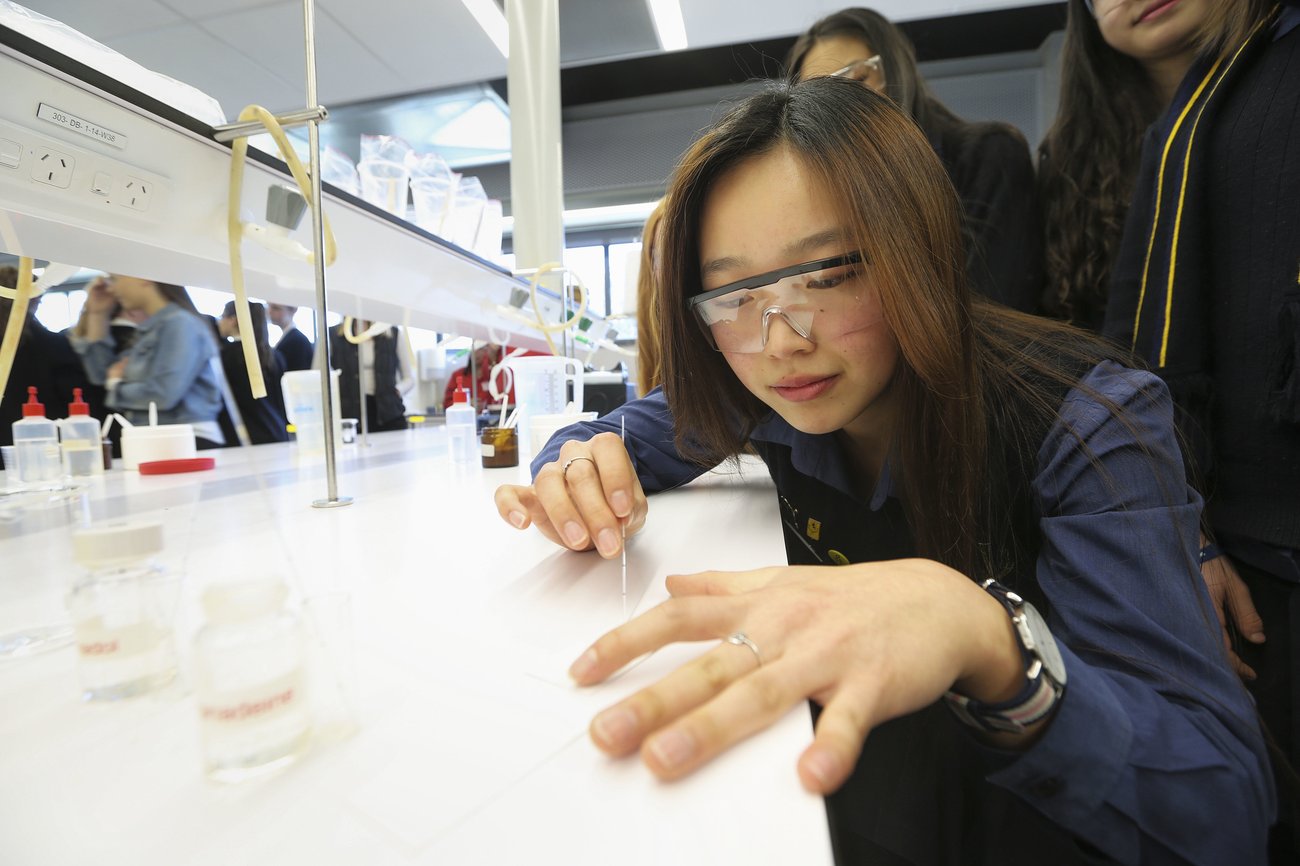

Thankfully, things are being done to help achieve equality beyond simply highlighting the issue. L’Oréal NZ’s third annual ‘For Girls in Science’ forum took place on September 9, and bringing 180 years 11 and 12 girls from 20 schools around Auckland to learn about science and science careers from some of the best female scientists in New Zealand. Supported by the University of Auckland, the forum included a talk by professor Margaret Brimble – the first New Zealander to receive the L’Oréal–UNESCO For Women in Science Laureate in 2007, second to be awarded the Rutherford Medal, and the third woman to win the Marsden Medal for a lifetime of outstanding achievement. There was also a panel discussion hosted by nanobiologist and science educator Dr Michelle Dickinson, popularly known as “Nanogirl,” and first-hand interactive laboratory tours.

Getting more young women into STEM careers is important, Brimble says. “I think it’s important to really capture the hearts and minds of these young girls when they’re at school, and probably back at primary school level, so they really are exposed to science as just a normal thing to do,” she explains. “It’s just like becoming a doctor or a lawyer or running a business – you have a career in science. It’s not something geeky that people don’t really relate to.”

While more young women are going into STEM careers than ever before, the struggle is keeping them in those careers, Brimble explains. “We have good entry levels into science from females,” she says. “We’re definitely over the 50 percent mark. Good retention now from undergraduate to postgraduate [too]. That wasn’t necessarily the case [before]. There are some areas that are still a little bit low, things like engineering. Chemistry we’re doing better. Biology we’ve been doing well. The problem then is they do their post-doctoral work, they do their PhD work, they do their post-doctoral fellowship. Then they’re hitting their 30s, and for women that’s when they’re thinking of having children. And so it’s that absolutely critical part when you’d normally embark on your independent career, suddenly the women have to fit in this family thing as well. And that’s really quite challenging. A lot of the positions you get as a young scientist are only short-term, short-contract type work. So it’s hard to keep going.”

Her words are backed up by data. A 2013 study by University of Texas at Austin researcher Jennifer Glass and other found that women leave STEM careers at more than twice the rate of women in other jobs. After 12 years, half of women in technical careers – mostly in engineering and computer science – had switched to a different field, compared to 20 percent of women in other professions.

From left: Dr Michelle Dickinson, Dr Zoë Hilton and Dr Christina Riesselman.

Another speaker at the event was University of Otago marine science and geology lecturer Dr Christina Riesselman. Having more women in STEM careers, and keeping them in those carrers, is key for diversity. “The more different minds you have chipping away [at a problem], the more solutions you’ll find.”

Dr Zoë Hilton, a researcher at the Cawthron Institute (New Zealand’s oldest scientific research institute) in Nelson who like Brimble and Riesselman also spoke at the event, agrees. “A lot of the issues we’re trying to solve now are global issues.”

Hilton and Riesselman also agree with Brimble on another thing: while it’s great that more women than ever before are going into STEM careers, it’s a struggle to keep some women in such careers. “Pay equality would help,” Hilton says.

She also says the biggest barriers for women are often just past the post-grad level, and include issues like employment policies that discriminate against women who choose to have children. “The one size fits all approach doesn’t always work,” explains Riesselman.

Dickinson says one way to tackle the problem is understanding that we all may have biases – and then think about how those biases are affecting others. “Everybody needs to look up unconscious bias and see if they have it,” she says. “We need to be aware.”

Dr Michelle Dickinson.

And just because there’s greater awareness doesn’t mean we shouldn’t keep encouraging young women to do anything they want to, she says – no matter how old they are. “Research shows that girls decide if science is for them or not by the age of 11,” she says. “I’m a firm believer you can achieve anything you set your mind to, if you work hard enough and find great people to share your journey.”

Brimble similarly believes in encouraging young women to go into STEM careers – and in encouraging young men to do the same, too. “I really encourage all my students – males and females – to get involved with innovation, alongside blue sky work.”

Tanya Abbott.

L’Oréal New Zealand group corporate communications manager Tanya Abbott says encouraging more young women to go into – and stay in – STEM careers can only produce positive results. “Although this isn’t a new issue, there are still myths, stereotypes and gender differences preventing girls from pursuing a career in science,” she explains. “Our aim is to inspire and demystify science as a profession for young women to encourage more of them take it up as a career.”

Those stereotypes, she says, continue to persist – and need to be abolished if equality is to be achieved. “There has been heightened awareness. But the research we’ve done [shows the problem] is as simplistic as stereotypes. They’re very basic, but very real.”

And the need to fight against those stereotypes, biases and other obstacles boils down to a very simple reason, Abbott says. “The world needs science. And science needs women.”