The world is split into two kinds of people. Some, when arriving at a new location where there’s a printer they’ve never used before and the time comes to make their device talk to it, will rise to – even relish – the challenge. And others look at the “add printer” screen and just start feeling a bit confused and sick. I am the second one. For a long time, that’s what I thought tech was. It was something you “got” or you didn’t. As such, the prospect of working on a conference such as Open Source Open Society felt like it was right in my Bermuda Triangle of “scary tech things I don’t understand”. I mean – Open Source is right there in the title. It’s code! Terrifying! Or so I thought.

That was before I learned that the principles behind open source are something that can be leveraged by everyone – not just programming boffins who understand tech. What’s more, I now understand that it’s never been more important that we get involved – that tech is for everyone, and the sector needs us more than it ever has, to shape what we want out of our future governments, internet, businesses, and world. And that open principles can help us do it. Here’s how.

1. Online democracy

If you’ve checked out the Australian news media this week, you’ll have seen their hot mess of an online census. It’s been terrible. But that’s no reason to set aside online democracy. It could improve accessibility, actually reduce distance in a way that makes it easier for us to talk to each other (this happens in Taiwan by using virtual reality for parallel town hall meetings in different cities!) and make it easier for us to participate. But the important thing is that the process of creating our online participation systems can no longer be centred around our old, closed, broken systems. The grandfather of the Estonian online government system – it’s a high tech utopia where all your Government business can be done online, easily and with no fuss – Linnar Viik says the biggest mistake governments make is assuming technology will fix their bad bureaucracy. Online tools amplify the system they’re representing. So if we want meaningful online democracy that allows for wider participation, we need to be part of helping create it.

2. Dealing with government

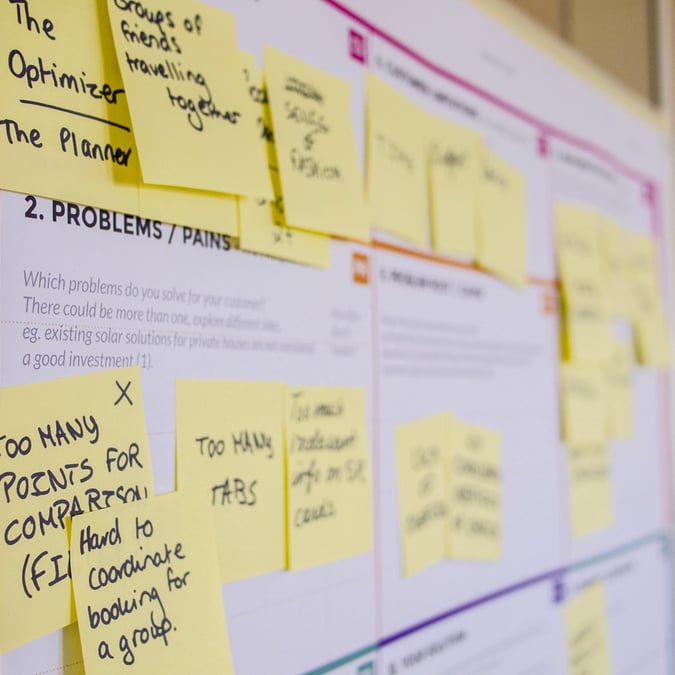

Dealing with government agencies can, at times, suck. This is an epiphany Eric Hysen had that’s helped shape how government relates to people in the US. Eric’s a former Google exec and is now the Executive Director of the US Digital Service at the Department of Homeland Security, where he’s trying to streamline immigration. One of his colleagues found, on the subway, a balled up bit of paper. On it was a list: of forms this person would have to fill in, and how much each form would cost, to bring a relative into the US. It was ridiculous. Eric thought, how do we make sure veterans can get access to services online efficiently? And people to healthcare? How might we reform our dealings with WINZ or Immigration or the IRD, if we open sourced the software and apps we’re dealing with, and open sourced the process by which we deal with Government? Find out where the sticking points are and fix them. This sounds quite hard, but at Open Source Open Society we’re going to get a bunch of government, business and tech sector people in a room for two days, chuck it in a blender, and see what we get.

3. Saving taxpayers’ money

Everyone loves a bargain. And a recent big win by open source advocates in government allows for potentially billions of dollars to be saved, if departments get on board. The new NZ GOAL policy framework and its Software Extension allows for production and licensing (using Creative Commons) more software that’s free to use and repurpose. This could be huge. It allows for one piece of code – say, something that improves accessibility, or a better contact form – to be used across government departments. It allows for the tech sector to help improve the code, and for the public to repurpose the code, and for business and government to take advantage of each other’s work and collaborate, saving money and doing a better job. If you think this will never happen, consider that the policy framework itself was created using online decision-making framework Loomio. This allowed everyone interested to comment on every bit of the policy, and for total transparency about what had been changed and how. And the people who debated it out online are all still alive. Go figure.

4. Holding authority accountable

Deputy Prime Minister Bill English has accepted an invitation to speak at the conference – and not just to give a speech. He’ll be taking questions about what the Government’s commitment to “open” exactly is, and what we can expect from them going forward. It’s a timely question. Another of our guests, civic hacker Audrey Tang, is from Taiwan, where open source principles have been used to create pathways between citizens and government, through which stuff actually gets done. Taiwan regulated Uber using a collaborative, open on/offline process that involved authorities, drivers, and the public. And on that note…

5. Planning our cities

What if we’d open sourced the Auckland Unitary Plan? I suppose public submissions are a form of that, but we could do better at creating accessible, transparent processes to improve the liveability of our cities. At Open Source Open Society, sharing economy strategist Darren Sharp will explain how we can democratise access to space and urban resources in our cities, and help us understand how co-design and co-governance can be used by civic institutions to collaborate with citizens.

6. Better teamwork

Open source isn’t just about code; it’s also a set of principles that can apply to the way we work. Around the world, companies are experimenting with openness and transparency to create more efficient, higher-functioning teams. It involves trust, creativity, and willingness. But really: why shouldn’t you have access to company decision-making, or know what everyone else gets paid? Why shouldn’t you have the chance to hack work and do it better? Bosses who aren’t letting their staff do this are missing out.

7. A media that serves us

It’s a scary time to be a journalist. And when a sector’s in constrained financial times, it tends to make businesses more protectionist, more closed, more jealous of guarding their IP. But what would it look like doing journalism in a more open society? Well, my dream is a world where you don’t have to file an OIA request for everything that has a noun in it. But I also don’t think closed silos of media necessarily does anyone any favours. Recently I heard Jane Patterson and Andrea Vance speaking about RNZ and TVNZ’s work together on the Panama Papers story; what was clear was that two top-notch teams had produced even better journalism working together than they would have separately. It gives you pause for thought.

8. Data that helps us care for people

The government, collectively, actually knows a lot more about us than they realise; they just often don’t join the dots. Data scientists like James Mansell are really good at joining the dots, and they’ve realised government systems like welfare could be better if data was shared more effectively between government. I definitely want to know what’s going to stop them posting all my tax files to a random guy in Levin. But what James and others have pioneered so far are systems that could reform where money is invested in our social system, using shared data. Invest a smaller amount earlier in an at-risk kid’s life and you could spare them a bigger, costlier intervention further down the track.

The message overall is that if you’ve got a website, an app, or you deal with data of any kind, you’re a tech business. This is terrifying for me as a person who’s scared of printers. But as the great Omar Little from The Wire once said, “The game is out there, and it’s either play or get played.” We can let every app we download have all our data for free and share it with whomever they like, we can keep allowing some of the most important decisions in our society to be made behind closed doors, or we can start talking about how to open up these processes, and work out how we’re going to demand they be open.

And as the great Douglas Rushkoff said, you either program or you’re being programmed. We can’t kid ourselves that tech isn’t for us, and that it doesn’t affect us, that we can sit this one out. Rushkoff tells a story about the US military finding it really easy to recruit young people who wanted to pilot drones – but near impossible to find those with the skills and know-how to programme how the drones worked. It seems like a no-brainer – why would you keep grinding away on something that someone else built without your input, all the while doing exactly what they’ve programmed you to do, when you can show up and build it yourself?

I will probably never figure out the printer thing. But I know enough to have ideas about what parts of our society, media and politics I want to see changed. And I want to be there to find out what it’d look like if we opened up the blueprint.